april 2005

To Prevent

a World Wasteland: A Proposal

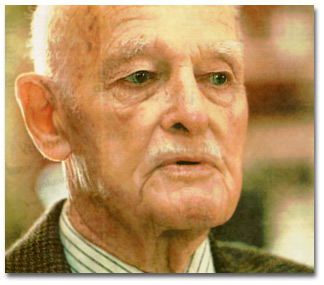

George F Kennan

From Foreign Affairs, April

1970

Climate crisis is not a future risk. It is today's

reality. As Myles Allen, a climate scientist at Oxford

University, warned recently: "The danger zone is not

something we are going to reach in the middle of this

century. We are in it now." (Roger Highfield,

'Screen saver weather trial predicts 10 deg rise in

British temperatures', Daily Telegraph, 31 January, 2005)David

Cromwell April 2005

Not even the most casual reader of the public prints of recent months and years could be unaware of the growing chorus of warnings from qualified scientists as to what industrial man is now doing -- by overpopulation, by plundering of the earth's resources, and by a precipitate mechanization of many of life's processes -- to the intactness of the natural environment on which his survival depends. "For the first time in the history of mankind," U.N. Secretary-General U Thant wrote, "there is arising a crisis of worldwide proportions involving developed and developing countries alike -- the crisis of human environment. ... It is becoming apparent that if current trends continue, the future of life on earth could be endangered."

Study and debate of these problems, and sometimes even governmental action, have been developing with cumulative intensity. This response has naturally concentrated largely on environmental deterioration as a national problem. It is normally within national boundaries that the first painful effects of deterioration are felt. It is at the national level that the main burden of legislation and administrative effort will admittedly have to be borne, if certain kinds of pollution and destruction are to be halted.

But it is also clear that the national perspective is not the only one from which this problem needs to be approached. Polluted air does not hang forever over the country in which the pollution occurs. The contamination of coastal waters does not long remain solely the problem of the nation in whose waters it has its origin. Wildlife -- fish, fowl and animal -- is no respecter of national boundaries, either in its movements or in the sources from which it draws its being. Indeed, the entire ecology of the planet is not arranged in national compartments; and whoever interferes seriously with it anywhere is doing something that is almost invariably of serious concern to the international community at large.

II

There is today in existence a considerable body of international arrangements, including several of great value, dealing with or affecting in one way or another the environmental problem. A formidable number of international organizations, some intergovernmental, some privately organized, some connected with the United Nations, some independently based, conduct programs in this field. As a rule, these programs are of a research nature. In most instances the relevance to problems of environmental conservation is incidental rather than central. While most of them are universal in focus, there are a few that approach the problem -- and in some instances very usefully -- at the regional level. Underlying a portion of these activities, and providing in some instances the legal basis for it, are a number of multilateral agreements that have environmental objectives or implications.

All this is useful and encouraging. But whether these activities are all that is needed is another question. Only a body fortified by extensive scientific expertise could accurately measure their adequacy to the needs at hand; and there is today, so far as the writer of these lines is aware, no body really charged with this purpose. In any case, it is evident that present activities have not halted or reversed environmental deterioration.

There is no reason to suppose, for example, that they will stop, or even reduce significantly at any early date, the massive spillage of oil into the high seas, now estimated at a million tons per annum and presumably steadily increasing. They will not assure the placing of reasonable limitations on the size of tankers or the enforcement of proper rules for the operation of these and other great vessels on the oceans. They will not, as they now stand, give humanity in general any protection against the misuse and plundering of the seabed for selfish national purposes. They will not put a stop to the proliferation of oil rigs in coastal and international waters, with all the dangers this presents for navigation and for the purity and ecological balance of the sea. They will not, except in a degree already recognized as quite unsatisfactory, protect the fish resources of the high seas from progressive destruction or depletion. They will not seriously reduce the volume of noxious effluence emerging from the River Rhine and being carried by the North Sea currents to other regions. They will not prevent the automobile gases and the sulphuric fumes from Central European industries from continuing to affect the fish life of both fresh and salt waters in the Baltic region. They will not stop the transoceanic jets from consuming -- each of them -- its reputed 35 tons of oxygen as it moves between Europe and America, and replacing them with its own particular brand of poisons. They will not ensure the observance of proper standards to govern radiological contamination, including disposal of radioactive wastes, in international media. They will not assure that all uses of outer space, as well as of the polar extremities of the planet, are properly controlled in the interests of humanity as a whole.

They may halt or alleviate one or another of these processes of deterioration in the course of time; but there is nothing today to give us the assurance that such efforts will be made promptly enough, or on a sufficient scale, to prevent a further general deterioration in man's environment, a deterioration of such seriousness as to be in many respects irreparable. Even to the non-scientific layman, the conclusion seems inescapable that if this objective is to be achieved, there will have to be an international effort much more urgent in its timing, bolder and more comprehensive in its conception and more vigorous in its execution than anything created or planned to date.

The General Assembly of the United Nations has not been indifferent to the gravity of this problem. Responding to the timely initiative and offer of hospitality of the Swedish government, it has authorized the Secretary-General to proceed at once with the preparation of a "United Nations Conference on the Human Environment," to be held at Stockholm in 1972. There is no question but that this undertaking, the initiation and pursuit of which does much credit to its authors, will be of major significance. But the conference will not be of an organizational nature; nor would it be suited to such a purpose. The critical study of existing vehicles for treating environmental questions internationally, as well as the creation of new organizational devices in this field, is a task that will have to be performed elsewhere. There is no reason why it should not be vigorously pursued even in advance of the Conference -- indeed, it is desirable for a number of reasons that it should. As was stated in the Secretary-General's report, "the decision to convene the Conference, and the preparations for it, should in no way be used to postpone or to cancel already initiated or planned programs of research or co÷peration, be they at the national, regional or international level. On the contrary, the problems involved are so numerous and so complicated that all efforts to deal with them immediately should be continued and intensified." It will be useful to attempt to picture the functions that need to be performed if this purpose is to be achieved.

III

The first of these would be to provide adequate facilities for the collection, storage, retrieval and dissemination of information on all aspects of the problem. This would involve not just assembling the results of scientific investigation but also keeping something in the nature of a register of all conservational activities at international, national, regional and even local levels across the globe. The task here is not one of conducting original research but rather of collecting and collating the results of research done elsewhere, and disposing of that information in a manner to make it readily available to people everywhere.

A second function would be to promote the co÷rdination of research and operational activities which now deal with environmental problems at the international level. The number of these is already formidable. To take a parallel from the American experience, it was calculated, when the President's Cabinet Committee on Environmental Quality was recently established in the White House, that there were already over 80 programs related to environmental questions being pursued just within the executive branch of the Federal Government. If a similar census were to be taken in the international field, the number would scarcely be less. A recent listing of just those bodies concerned with the peaceful uses of outer space noted 17 entities.

These activities have grown up, for the most part, without central structure or concept. There is not today even any assurance, or any means of assuring, that they cover all the necessary fields. The disadvantages of such a situation -- possibilities for confusion, duplication and omission -- are obvious.

A third function would be to establish international standards in environmental matters and to extend advice and help to individual governments and to regional organizations in their efforts to meet these standards. It is not a question here of giving orders, exerting authority or telling governments what to do. The function is in part an advisory one and in part, no doubt, hortatory: a matter of establishing and explaining requirements, of pressing governments to accept and enforce standards, of helping them to overcome domestic opposition. The uses of an international authority, when it comes to supporting and stiffening the efforts of governments to prevail against commercial, industrial and military interests within their respective jurisdictions, have already been demonstrated in other instances, as, for example, in the European Iron and Steel Community. They should not be underestimated here.

The fourth function that cries out for performance is from the standpoint of the possibilities in international (as opposed to national or regional) action, the most important of all. In contrast to all the others, it relates only to what might be called the great international media of human activity: the high seas, the stratosphere, outer space, perhaps also the Arctic and Antarctic -- media which are subject to the sovereign authority of no national government. It consists simply of the establishment and enforcement of suitable rules for all human activities conducted in these media. It is a question not just of conservational considerations in the narrow sense but also of providing protection against the unfair exploitation of these media, above all the plundering or fouling or damaging of them, by individual governments or their nationals for selfish parochial purposes. Someone, after all, must decide at some point what is tolerable and permissible here and what is not; and since this is an area in which no sovereign government can make these determinations, some international authority must ultimately do so.

No one should be under any illusions about the far-reaching nature, and the gravity, of the problems that will have to be faced if this fourth function is to be effectively performed. There will have to be a determined attack on the problem of the "flags of convenience" for merchant shipping, and possibly their replacement by a single international rÚgime and set of insignia for vessels plying the high seas. One will have to tackle on a hitherto unprecedented scale the thorny task of regulating industrialized fishing in international waters. There may have to be international patrol vessels charged with powers of enforcement in each of these fields. Systems of registration and licensing will have to be set up for uses made of the seabed as well as outer space; and one will have to confront, undaunted, the formidable array of interests already vested in the planting of oil rigs across the ocean floor.

For all of these purposes, the first step must be, of course, the achievement of adequate international consensus and authorization in the form of a multilateral treaty or convention. But for this there will have to be some suitable center of initiation, not to mention the instrument of enforcement which at a later point will have to come into the picture.

IV

What sort of authority holds out the greatest promise of assuring the effective performance of these functions?

It must first be noted that most of them are now being performed in some respects and to some degree by international organizations of one sort or another. The United Nations Secretariat does register (albeit ex post facto and apparently only for routine purposes) such launchings of objects into outer space as the great powers see fit to bring to its attention. The International Maritime Consultative Organization is concerned with the construction and equipping of ships carrying oil or other hazardous or noxious cargos. The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation does assemble data on radiation and radioactivity in the environment and give advice to individual governments concerning standards and tolerances in this field. The Organization for Economic Development and Co÷peration has recently announced its intention to work out international tolerance levels for pollutants and to tax those of its members which exceed these limits.

This list could go on for pages. Dozens of organizations collect information. Several make recommendations to governments. Some even exercise a limited co÷rdinating role in individual fields. They cover a significant portion of needs; and they obviously cannot be ignored when it comes to the examination of the best organizational response to the problem in question. On the contrary, any approach that failed to take advantage of the work they are already accomplishing, any approach in particular that attempted to duplicate their present activity or to centralize it completely, would assuredly fail. But even in their entirety, they do not cover the whole spectrum of the functions that need to be performed, as listed above; and those that they do perform they perform, for the most part, inadequately.

The question therefore poses itself: How should these organizations be reinforced or expanded? Do they provide in themselves an adequate basis for the necessary expansion of function and activity? Or do they need to be supplemented by new organizational forms, and, if so, of what nature? Is there need for a central organization to bring all these activities under a single hat? Should there be several centers? Or none at all?

There is a view -- and it is based on impressive experience and authority -- which holds that there is no need for any unifying effort in these various forms of activity, at least not beyond such limited co÷rdinating influence as United Nations bodies are able to exercise today; that any effort in this direction might only further confuse an already confused pattern; and that the most promising line of attack is for governments to intensify their support of activities already in progress, letting them develop separately according to function, letting one set of organizations continue to occupy itself with radiology, another with other forms of air pollution, another with the ecology of fresh water lakes and rivers, another with wildlife, another with oil pollution on the high seas, another with the ocean bed, etc. This is, of course, in many ways the easiest course. Existing efforts, under this procedure, are not disturbed. Existing arrangements for international control and support are not placed in question. Established competencies, sometimes conquered and defended in past years with much effort, are not jeopardized.

But there are weighty considerations that argue against such a course. A number of the existing organizations, including particularly ones connected with the United Nations, have primarily a developmental focus; yet developmental considerations are frequently in conflict with the needs of environmental conservation. Others are staffed, at least in considerable part, by persons whose professional enthusiasm runs to the exploitation of the very natural media or resources whose protection is here at stake. Others are closely connected with commercial interests engaged in just this sort of exploitation.

There is a considerable body of opinion, particularly in U. N. circles, to the effect that it is a mistake to separate the function of conservation and protection of natural resources from that of the development and exploitation of these resources for productive purposes. According to this view, there should not be separate organizations concerned with conservation. Considerations of an environmental nature should rather be built from the outset into all those activities that are concerned with the productive exploitation of natural resources, so that environmental needs would be met, so to speak, at the source.

This writer must respectfully disagree. This is an

area in which exploitative motives cannot usefully be

mingled with conservational ones. What is needed here is

a watchdog; and the conscience and sense of duty of the

watchdog must not be confused by contrary duties and

undertakings. It may be boldly asserted that of the two

purposes in question, conservation should come first. The

principle should be that one exploits what a careful

regard for the needs of conservation leaves to be

exploited, not that one conserves what a liberal

indulgence of the impulse to development leaves to be

conserved.

V

What is lacking in the present pattern of approaches would seem to be precisely an organizational personality -- part conscience, part voice -- which has at heart the interests of no nation, no group of nations, no armed force, no political movement and no commercial concern, but simply those of mankind generally, together -- and this is important -- with man's animal and vegetable companions, who have no other advocate. If determinations are to be made of what is desirable from the standpoint of environmental conservation and protection, then they are going to have to proceed from a source which, in addition to including scientific competence and having qualified access to all necessary scientific data, sees things from a perspective which no national body -- and no international one whose function is to reconcile conflicting national interests -- can provide.

The process of compromise of national interests will of course have to take place at some point in every struggle against environmental deterioration at the international level. But it should not occur in the initial determination of what is and is not desirable from the conservational standpoint. This determination should at first be made, so to speak, in its pure form, or as near as one can get to it. It should serve as the point of departure for the long, wearisome, often thorny and frustrating, road of accommodation that will have to be traversed before it can be transformed into reality. But it should not itself be compromised at the outset.

Nor is this the only reason why one cannot make do with just the reinforcement of what now exists. If the present process of deterioration is to be halted, things are going to have to be done which will encounter formidable resistance from individual governments and powerful interests within individual countries. Only an entity that has great prestige, great authority and active support from centers of influence within the world's most powerful industrial and maritime nations will be able to make headway against such recalcitrance. One can conceive of a single organization's possessing such prestige and authority. It is harder to conceive of the purpose being served by some fifty to a hundred organizations, each active in a different field, all of them together presenting a pattern too complicated even to be understood or borne in mind by the world public.

All of this would seem to speak for the establishment of a single entity which, while not duplicating the work of existing organizations, could review this work from the standpoint of man's environmental needs as a whole, could make it its task to spot the inadequacies and identify the unfilled needs, could help to keep governments and leaders of opinion informed as to what ought to be done to meet minimum needs, could endeavor to assure that proper rules and standards are established wherever they are needed, and could, where desired, take a hand, vigorously and impartially, in the work of enforcement of rules and standards. It would not have to perform all these various functions itself -- except perhaps where there was no one else to do so. Its responsibility should be rather to define their desirable dimensions and to exert itself, and use its influence with governments, to the end that all of them were performed by someone, and in an adequate way.

This entity, while naturally requiring the initiative of governments for its inception and their continued interest for its support, would have to be one in which the substantive decisions would be taken not on the basis of compromise among governmental representatives but on the basis of collaboration among scholars, scientists, experts, and perhaps also something in the nature of environmental statesmen and diplomats -- but true international servants, bound by no national or political mandate, by nothing, in fact, other than dedication to the work at hand.

VI

It is impossible to picture an entity of this nature without considering, in the first instance, the possible source of its initiation and sponsorship in the international community. Who would take the lead in establishing it? From whom would it draw its financial resources? Who would constitute the ultimate sanction for its existence and its authority?

Obviously no single government could stand as the

patron for such an agency. To seek, on the other hand,

the sanction of the entire international community for

its inception and activity would scarcely be a promising

undertaking. Aside from the fact that this would then

necessitate procedures practically indistinguishable from

those of the United Nations itself, it would mean

involving in the control and operation of the entity to

be established a host of smaller and less developed

countries which could contribute very little to the

solution of the problems at hand. It would also involve

formidable delays and heavy problems of decision-taking.

Were this to be the course selected, one would do better

to content one's self, throughout, with the existing

facilities of the United Nations, which represent just

about the limit of what can be accomplished on the basis

of a universal, or near-universal, governmental

consensus.

One is driven to the conclusion that if anything very constructive is going to be accomplished along this line, the interest and initiative will have to proceed from a relatively small group of governments; and logic suggests that these should be those of the leading industrial and maritime nations. It is they whose economies produce, in the main, the problem of pollution. It is they, again, who have the means to correct it. It is they, finally, who have the scientific and other resources to analyze the problem and to identify the most promising lines of solution. The devastation of the environment is primarily, though not exclusively, a function of advanced industrial and urban society. The correction of it is primarily a problem for the advanced nations.

One can conceive, then, by an act of the imagination, of a small group of advanced nations, consisting of roughly the ten leading industrial nations of the world, including communist and non-communist ones alike, together (mainly for reasons of their maritime interests) with the Scandinavians and perhaps with the Benelux countries as a bloc, constituting themselves something in the nature of a club for the preservation of natural environment, and resolving, then, in that capacity, to bring into being an entity -- let us call it initially an International Environmental Agency -- charged with the performance, at least on their behalf, of the functions outlined above. It would not, however, be advisable that this agency should be staffed at the operating level with governmental representatives or that it should take its decisions on the basis of intergovernmental compromise. Its operating personnel should rather have to consist primarily of people of scientific or technical competence, and the less these were bound by disciplinary relationships to individual governments, the better. One can imagine, therefore, that instead of staffing and controlling this agency themselves, the governments in question might well insert an intermediate layer of control by designating in each case a major scientific institution from within their jurisdiction -- an Academy of Science or its equivalent -- to act as a participating organization. These scientific bodies would then take over the responsibility for staffing the agency and supervising its operations.

It may be argued that under such an arrangement the participating institutions from communist countries would not be free agents, would enjoy no real independence, and would act only as stooges for their governments. As one who has had occasion both to see something of Russia and to disagree in public on a number of occasions with Soviet policies, the writer of this article is perhaps in a particularly favorable position to express his conviction that the Soviet Academy of Sciences, if called upon by its government to play a part in such an undertaking, would do so with an integrity and a seriousness of purpose worthy of its great scientific tradition, and would prove a rock of strength for the accomplishment of the objectives in question.

The agency would require, of course, financial support from the sponsoring governments. There would be no point in its establishment if one were not willing to support it generously and regularly; and one should not underestimate the amount of money that would be required. It might even run eventually to as much as the one-hundredth part of the military budgets of the respective governments for the same period of time, which would of course be a very substantial sum. Considering that the threat the agency would be designed to confront would be one by no means less menacing or less urgent than those to which the military appropriations are ostensibly devoted, this could hardly be called exorbitant.

The first task of such an agency should be to establish the outstanding needs of environmental conservation in the several fields, to review critically the work and the prospects of organizations now in existence, in relation to those needs, to identify the main lacunae, and to make recommendations as to how they should be filled. Such recommendations might envisage the concentration of one or another sort of activity in a single organization. They might envisage the strengthening of certain organizations, the merging of others. They might suggest the substance of new multilateral treaty provisions necessary to supply the foundation for this or that function of regulation and control. They might involve the re-allotment of existing responsibility for the development of standards, or the creation of new responsibilities of this nature. In short, a primary function of the Agency would be to advise governments, regional organizations and public opinion generally on what is needed to meet the environmental problem internationally, and to make recommendations as to how these needs can best be met. It would then of course be up to governments, the sponsoring ones and others as well, to implement these recommendations in whatever ways they might decide or agree on.

This, as will be seen, would be initially a process of study and advice. It would never be entirely completed; for situations would be constantly changing, new needs would be arising as old ones were met, the millennium would never be attained. But one could hope that eventually, as powers were accumulated and authority delegated under multilateral treaty arrangements, the Agency could gradually take over many of the functions of enforcement for such international arrangements as might require enforcement in the international media, and in this way expand its function and designation from that of an advisory agency to that of the single commanding International Environmental Authority which the international community is bound, at some point, to require.

All this, however, belongs to a later phase of development which it is idle to attempt to envisage in an enquiry so preliminary as this. In problems of international organizations, as in war, one does well to follow the Napoleonic principle: "On s'engage et puis on voit." To engage oneself means, in this instance, to bring into being the personality. The rest will follow.

VII

The above is intended only as a suggestion of certain

lines along which international action in this field

might usefully and hopefully proceed. In the mind of the

writer, these considerations would have validity even if

founded only on the strictest and narrowest view of the

environmental factors alone. They need no extraneous

arguments for their justification.

It would be wrong, however, to close this discussion

without noting that no such undertaking could be without

its political and psychological by-products. The energies

and resources men have to devote to international

activities are not unlimited. To the extent that a place

can be found in their hopes and enthusiasms for

constructive and hopeful efforts, these must proceed at

least to some extent at the expense of the sterile,

morbid and immensely dangerous preoccupations that are

now pursued under the heading of national defense.

Not only the international scientific community but the world public at large has great need, at this dark hour, of a new and more promising focus of attention. The great communist and Western powers, particularly, have need to replace the waning fixations of the cold war with interests which they can pursue in common and to everyone's benefit. For young people the world over, some new opening of hope and creativity is becoming an urgent spiritual necessity. Could there, one wonders, be any undertaking better designed to meet these needs, to relieve the great convulsions of anxiety and ingrained hostility that now rack international society, than a major international effort to restore the hope, the beauty and the salubriousness of the natural environment in which man has his being?

ENGLAND 2005 JOURNALISTS WITHOUT

RESPONSIBILITY?

DAVID CROMWELL

Consider, for example, Michael McCarthy, environment

editor of the Independent. McCarthy described how he

"was taken aback" at dramatic scientific

warnings of "major new threats" at a recent

climate conference in Exeter. One frightening prospect is

the collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet, previously

considered stable, which would lead to a 5-metre rise in

global sea level. As McCarthy notes dramatically:

"Goodbye London; goodbye Bangladesh".

On the way back from Exeter on the train, he mulls over

the conference findings with Paul Brown, environment

correspondent of the Guardian:

"By the time we reached London we knew what the

conclusion was. I said: 'The earth is finished.' Paul

said: 'It is, yes.' We both shook our heads and gave that

half-laugh that is sparked by incredulity. So many

environmental scare stories, over the years; I never

dreamed of such a one as this.

Following McCarthy's anguished return to the

Independent's comfortable offices in London, one searches

in vain for his penetrating news reports on how corporate

greed and government complicity have dragged humanity

into this abyss. One searches in vain, too, for anything

similar by Paul Brown in The Guardian.

The notion of government and big business

perpetrating climate crimes against humanity is simply

off the news agenda. A collective madness of suffocating

silence pervades the media, afflicting even those editors

and journalists that we are supposed to regard as the

best.

Contraction and Convergence: Climate Logic for Survival

In 1992, the United Nations Framework Convention on

Climate Change was agreed. The objective of the

convention is to "stabilise greenhouse gas

concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that will

avoid dangerous rates of climate change." The Kyoto

protocol, which came into force in February, requires

developed nations to cut emissions by just 5 per cent,

compared to 1990 levels. This is a tiny first step, and

is far less than the cuts required, which are around 80

per cent.

One of the major gaps in the climate 'debate' is the

deafening silence surrounding contraction and convergence

(C&C). This proposal by the London-based Global

Commons Institute would cut greenhouse gas emissions in a

fair and timely manner, averting the worst climatic

impacts. Unlike Kyoto, it is a global framework involving

all countries, both 'developed' and 'developing'.

C&C requires that annual emissions of greenhouse

gases contract over time to a sustainable level. The aim

would be to limit the equivalent concentration of carbon

dioxide in the atmosphere to a safe level. The

pre-industrial level, in 1800, was 280 parts per million

by volume (ppmv). The current level is around 380 ppmv,

and it will exceed 400 ppmv within ten years under a

business as usual scenario. Even if we stopped burning

fossil fuels today, the planet would continue to heat up

for more than a hundred years. In other words, humanity

has already committed life on the planet to considerable

climate-related damages in the years to come.

Setting a 'safe' limit of atmospheric carbon dioxide

concentration actually means estimating a limit beyond

which damage to the planet is unacceptable. This may be

450 ppmv; or it may be that the international community

agrees on a target lower than the present atmospheric

level, say 350 ppmv. Once the target is agreed, it is a

simple matter to allocate an equitable 'carbon budget' of

annual emissions amongst the world's population on a per

capita basis. This is worked out for each country or

world region (e.g. the European Union).

The Global Commons Institute's eye-catching computer

graphics illustrate past emissions and future allocation

of emissions by country (or region), achieving per capita

equality by 2030, for example. This is the convergence

part of C&C. After 2030, emissions drop off to reach

safe levels by 2100. This is the contraction. (Further

information on C&C, with illustrations, can be found

at http://www.gci.org.uk).

Recall that the objective of the UN Framework Convention

on Climate Change is to "stabilise greenhouse gas

concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that will

avoid dangerous rates of climate change." Its basic

principles are precaution and equity. C&C is a simple

and powerful proposal that directly embodies both the

convention's objective and principles.

Last year, the secretariat to the UNFCCC negotiations

declared that achieving the treaty's objective

"inevitably requires Contraction and

Convergence". C&C is supported by an impressive

array of authorities in climate science, including

physicist Sir John Houghton, the former chair of the

science assessment working group of the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change (1988-2002). Indeed, the IPCC,

comprising the world's recognised climate experts, has

announced that: "C&C takes the rights-based

approach to its logical conclusion."

The prestigious Institute of Civil Engineers in London

recently described C&C as "an antidote to the

expanding, diverging and climate-changing nature of

global economic development". The ICE added that

C&C "could prove to be the ultimate

sustainability initia?tive." (Proceedings of the

Institution of Civil Engineers, London, paper 13982,

December 2004)

In February 2005, Aubrey Meyer of the Global Commons

Institute was given a lifetime's achievement award by the

Corporation of London. Nominations had been sought for

"the person from the worlds of business, academia,

politics and activism seeking the individual who had made

the greatest contribution to the understanding and

combating of climate change, leading strategic debate and

policy formation."

Although Meyer is at times understandably somewhat

despondent at the enormity of the task ahead, he sees

fruitful signs in the global grassroots push for

sustainable development, something which "is

impossible without personal and human development. These

are things we have to work for so hope has momentum as

well as motive." ('GCI's Meyer looks ahead',

interview with Energy Argus, December 2004, p. 15;

reprinted in http://www.gci.org.uk/briefings/EAC_document_3.pdf,

p. 27)

And that momentum of hope is building. C&C has

attracted statements of support from leading politicians

and grassroots groups in a majority of the world's

countries, including the Africa Group, the Non-Aligned

Movement, China and India. C&C may well be the only

approach to greenhouse emissions that developing

countries are willing to accept. That, in turn, should

grab the attention of even the US; the Bush

administration rejected the Kyoto protocol ostensibly, at

least, because the agreement requires no commitments from

developing nations. Kyoto involves only trivial cuts in

greenhouse gas emissions, as we noted above, and the

agreement will expire in 2012. A replacement agreement is

needed fast.

On a sane planet, politicians and the media would now be

clamouring to introduce C&C as a truly global,

logical and equitable framework for stabilising the

atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide. Rational and

balanced coverage of climate change would be devoting

considerable resources to discussion of this

groundbreaking proposal.

It would be central to news reports of international

climate meetings as a way out of the deadlock of

negotiations; Jon Snow of Channel 4 news would be hosting

hour-long live debates; the BBC's Jeremy Paxman would

demand of government ministers why they had not yet

signed up to C&C; ITN's Trevor Macdonald would

present special documentaries from a multimillion pound

ITN television studio; newspaper editorials would analyse

the implications of C&C for sensible energy policies

and tax regimes; Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace

would be endlessly promoting C&C to their supporters.

Instead, a horrible silence prevails.

Write to Michael McCarthy, environment editor of the

Independent: Email: m.mccarthy@independent.co.uk

Write to Geoffrey Lean, environment editor of the

Independent on Sunday: Email: g.lean@independent.co.uk

Write to Charles Clover, environment editor of the Daily

Telegraph: Charles.Clover@telegraph.co.uk

Write to Paul Brown, environment correspondent of the

Guardian: Email: paul.brown@guardian.co.uk

Write to John Vidal, environment editor of the Guardian:

Email: john.vidal@guardian.co.uk

Please also send all emails to DAVID CROMWELL at Media

Lens: Email: editor@medialens.org

World On Brink Of Disaster,

Say Top Scientists

Authoritative Study Has Found Disturbing

Evidence Of Man-Made Degradation

By Steve Connor

The Independent - UK

3-30-5- Planet Earth stands on the cusp of disaster and people should no longer take it for granted that their children and grandchildren will survive in the environmentally degraded world of the 21st century. This is not the doom-laden talk of green activists but the considered opinion of 1,300 leading scientists from 95 countries who will today publish a detailed assessment of the state of the world at the start of the new millennium.

- The report does not make jolly reading. The academics found that two-thirds of the delicately-balanced ecosystems they studied have suffered badly at the hands of man over the past 50 years.

- The dryland regions of the world, which account for 41 per cent of the earth's land surface, have been particularly badly damaged and yet this is where the human population has grown most rapidly during the 1990s.

- Slow degradation is one thing but sudden and irreversible decline is another. The report identifies half a dozen potential "tipping points" that could abruptly change things for the worse, with little hope of recovery on a human timescale.

- Even if slow and inexorable degradation does not lead to total environmental collapse, the poorest people of the world are still going to suffer the most, according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, which drew on 22 national science academies from around the world.

- Walt Reid, the leader of the report's core authors, warned that unless the international community took decisive action the future looked bleak for the next generation. "The bottom line of this assessment is that we are spending earth's natural capital, putting such strain on the natural functions of earth that the ability of the planet's ecosystems to sustain future generations can no longer be taken for granted," Dr Reid said.

- "At the same time, the assessment shows that the future really is in our hands. We can reverse the degradation of many ecosystem services over the next 50 years, but the changes in policy and practice required are substantial and not currently under way," he said.

- The assessment was carried out over the past three years and has been likened to the prestigious Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change - set up to investigate global warming - for its expertise in the many specialisms that make up the broad church of environmental science.

- In summary, the scientists concluded that the planet had been substantially "re-engineered" in the latter half of the 20th century because of the pressure placed on the earth's natural resources by the growing demands of a larger human population.

- "Over the past 50 years, humans have changed ecosystems more rapidly and extensively than at any time in human history, largely to meet rapidly growing demands for food, fresh water, timber and fibre," the reports says.

- The full costs of this are only now becoming apparent. Some 15 of the 24 ecosystems vital for life on earth have been seriously degraded or used unsustainably - an ecosystem being defined as a dynamic complex of plants, animals and micro-organisms that form a functional unit with the non-living environment in which the coexist.

- The scale of the changes seen in the past few decades has been unprecedented. Nearly one-third of the land surface is now cultivated, with more land being converted into cropland since 1945 than in the whole of the 18th and 19th centuries combined.

- The amount of water withdrawn from rivers and lakes for industry and agriculture has doubled since 1960 and there is now between three and six times as much water held in man-made reservoirs as there is flowing naturally in rivers.

- Meanwhile, the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus that has been released into the environment as a result of using farm fertilisers has doubled in the same period . More than half of all the synthetic nitrogen fertiliser ever used on the planet has been used since 1985.

- This sudden and unprecedented release of free nitrogen and phosphorus - important mineral nutrients for plant growth - has triggered massive blooms of algae in the freshwater and marine environments. This is identified as a potential "tipping point" that can suddenly destroy entire ecosystems. "The Millennium Assessment finds that excessive nutrient loading is one of the major problems today and will grow significantly worse in the coming decades unless action is taken," Dr Reid said.

- "Surprisingly, though, despite a major body of monitoring information and scientific research supporting this finding, the issue of nutrient loading barely appears in policy discussions at global levels and only a few countries place major emphasis on the problem.

- "This issue is perhaps the area where we find the biggest 'disconnect' between a major problem related to ecosystem services and the lack of policy action in response," he said.

- Abrupt changes are one of the most difficult things to predict yet their impact can be devastating. But is environmental collapse inevitable?

- "Clearly, the dual trends of continuing degradation of most ecosystem services and continuing growth in demand for these same services cannot continue," Dr Reid said.

- "But the assessment shows that over the next 50 years, the risk is not of some global environmental collapse, but rather a risk of many local and regional collapses in particular ecosystem services. We already see those collapses occurring - fisheries stocks collapsing, dead zones in the sea, land degradation undermining crop production, species extinctions," he said.

- Between 1960 and 2000, the world population doubled from three billion to six billion. At the same time, the global economy increased more than six-fold and the production of food and the supply of drinking water more than doubled, with the consumption of timber products increasing by more than half.

- Meanwhile, human activity has directly affected the diversity of wild animals and plants. There have been about 100 documented extinctions over the past century but scientists believe that the rate at which animals and plants are dying off is about 1,000 times higher than natural, background levels.

- "Humans are fundamentally and to a significant extent irreversibly changing the diversity of life on earth and most of these changes represent a loss of biodiversity," the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment says.

- The distribution of species across the world is becoming more homogenous as some unique animals and plants die out and other, alien species are introduced into areas in which they would not normally live, often with devastating impact.

- For example, the Baltic Sea contains 100 non-native species, of which about one-third come from the Great Lakes of North America. Meanwhile, a similar proportion of the 170 non-native species found in the Great Lakes come from the Baltic.

- "In other words, the species in any one region of the world are becoming more similar to other regions.... Some 10 to 30 per cent of mammals, birds and amphibians are currently threatened with extinction. Genetic diversity has declined globally, particularly among cultivated species," the report says.

- Agricultural intensification, which brought about the green revolution that helped to feed the world in the latter part of the 20th century, has increased the tendency towards the loss of genetic diversity. "Currently 80 per cent of wheat area in developing countries and three-quarters of all rice planted in Asia is now planted to modern varieties," the report says. Dr Reid said that the authors of the assessment were most worried about the state of the earth's drylands - an area covering 41 per cent of the land surface and home to a total of two billion people, many of them the poorest in the world.

- Drylands are areas where crop production or pasture for livestock is severely limited by rainfall. Some 90 per cent of the world's dryland regions occur in developing countries where the availability of fresh water is a growing problem.

- One-third of the world's people live in dryland regions that have access to only 8 per cent of the world's renewable supply of water, the scientists found. "We were particularly alarmed by the evidence of strong linkages between the degradation of ecosystem services in drylands and poverty in those regions," Dr Reid said.

- "Moreover, while historically, population growth has been highest in either urban areas or the most productive ecosystems such as cultivated lands, this pattern changed in the 1990s and the highest percentage rate of growth is now in drylands - ecosystems with the lowest potential to support that growth.

- "These problems of ecosystem degradation and the harm it causes for human well-being clearly help set the stage for the conflict that we see in many dryland regions including parts of Africa and central Asia," he said.

- Poor people living in dryland regions are at the greatest risk of environmental collapse. Many of them already live unsustainably - between 10 and 20 per cent of the soil in the drylands are eroded or degraded.

- "Development prospects in dryland regions of developing countries are especially dependent on actions to slow and reverse the degradation of ecosystems," the Millennium Assessment says.

- So what can be done in a century when the human population is expected to increase by a further 50 per cent?

- The board of directors of the Millennium Assessment said in a statement: "The overriding conclusion of this assessment is that it lies within the power of human societies to ease the strains we are putting on the nature services of the planet, while continuing to use them to bring better living standards to all.

- "Achieving this, however, will require radical changes in the way nature is treated at every level of decision-making and new ways of co-operation between government, business and civil society. The warning signs are there for all of us to see. The future now lies in our hands," it said.

- Asked what we should do now and what we should plan to do over the next 50 years, Dr Reid replied that there must be a fundamental reappraisal of how we view the world's natural resources. "The heart of the problem is this: protection of nature's services is unlikely to be a priority so long as they are perceived to be free and limitless by those using them," Dr Reid said.

- "We simply must establish policies that require natural costs to be taken into account for all economic decisions," he added.

- "There is a tremendous amount that can be done in the short term to reduce degradation - for example, the causes of some of the most significant problems such as fisheries collapse, climate change, and excessive nutrient loading are clear - many countries have policies in place that encourage excessive harvest, use of fossil fuels, or excessive fertilisation of crops.

- "But as important as these short-term fixes are, over the long term humans must both enhance the production of many services and decrease our consumption of others. That will require significant investments in new technologies and significant changes in behaviour," he explained.

- Many environmentalists would agree, and they would like politicians to go much further.

- "The Millennium Assessment cuts to the heart of one of the greatest challenges facing humanity," Roger Higman, of Friends of the Earth, said.

- "That is, we cannot maintain high standards of living, let alone relieve poverty, if we don't look after the earth's life-support systems," Mr Higman said.

- "Yet the assessment hasn't gone far enough in specifying the radical solutions needed. At the end of the day, if we are to respect the limits imposed by nature, and ensure the well-being of all humanity, we must manage the global economy to produce a fairer distribution of the earth's resources," he added.

- THE TIPPING POINTS TO CATASTROPHE

- NEW DISEASES

- As population densities increase and living space extends into once pristine forests, the chances of an epidemic of a new infectious agent grows. Global travel accentuates the threat, and the emergence of Sars and bird flu are prime examples of diseases moving from animals to humans.

- ALIEN SPECIES

- The introduction of an invasive species - whether animal, plant or microbe - can lead to a rapid change in ecosystems. Zebra mussels introduced into North America led to the extinction of native clams and the comb jellyfish caused havoc to 26 major fisheries species in the Black Sea.

- ALGAL BLOOMS

- A build up of man-made nutrients in the environment has already led to the threshold being reached when algae blooms. This can deprive fish and other wildlife of oxygen as well as producing toxic substances that are a danger to drinking water.

- CORAL REEF COLLAPSE

- Reefs that were dominated by corals have suddenly changed to being dominated by algae, which have taken advantage of the increases in nutrient levels running off from terrestrial sources. Many of Jamaica's coral reefs have now become algal dominated.

- FISHING STOCKS

- Overfishing can, and has, led to a collapse in stocks. A threshold is reached when there are too few adults to maintain a viable population. This occurred off the east coast of Newfoundland in 1992 when its stock of Atlantic cod vanished.

- CLIMATE CHANGE

- In a warmer world, local vegetation or land cover can change, causing warming to become worse. The Sahel region of North Africa depends on rainfall for its vegetation. Small changes in rain can result in loss of vegetation, soil erosion and further decreases in rainfall.

- ę2005 Independent News & Media (UK) Ltd.

- http://news.independent.co.uk/