april 2005

Mr. Halperin said Mr. Kennan understood the need to talk

truth to power no matter how unpopular, and made clear

his belief that containment was primarily a political and

diplomatic policy rather than a military one. "His

career since is clear proof that no matter how important

the role of the policy planning director, a private

citizen can have an even greater impact with the strength

of his ideas."

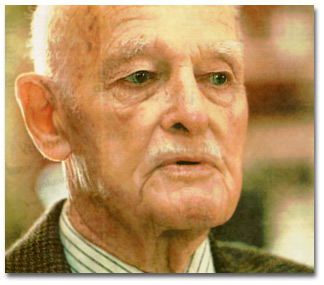

George F. Kennan Dies at

101; Leading Strategist of Cold War

By TIM WEINER and BARBARA

CROSSETTE

Published: March 18, 2005

www.nytimes.com

George F. Kennan, the American diplomat who did more than

any other envoy of his generation to shape United States

policy during the cold war, died on Thursday night in

Princeton, N.J. He was 101.

Mr. Kennan was the man to whom the White House and the

Pentagon turned when they sought to understand the Soviet

Union after World War II. He conceived the cold-war

policy of containment, the idea that the United States

should stop the global spread of Communism by diplomacy,

politics, and covert action - by any means short of war.

| G.F.KENNAN,America’s

most distinguished diplomatic historian delivered

the following address on the occasion of

receiving the award of the Albert Einstein Peace

Prize at Princeton University. Adequate words are lacking to express the full seriousness of our present situation. It is not just that our government and the Soviet government are for the moment on a collision course politically; it is the fact that the ultimate sanction behind the policies of both these governments is a type and volume of weaponry that could not possibly be used without utter disaster for everyone concerned. For over thirty years wise and far-seeing people have been warning us about the futility of any war fought with these weapons and about the dangers involved in their very cultivation. Some of the first of these voices were those of great scientists, including outstandingly Albert Einstein himself. But there has been no lack of others. Every president of this country, from Dwight Eisenhower to Jimmy Carter, has tried to remind us that there could be no such thing as victory in a war fought with such weapons. So have a great many other eminent persons. How have we got ourselves into this dangerous mess? |

As the State Department's first

policy planning chief in the late 1940's,

serving Secretary of State George C. Marshall, Mr. Kennan

was an intellectual architect of the Marshall Plan, which

sent billions of dollars of American aid to nations

devastated by World War II. At the same time, he

conceived a secret "political warfare" unit

that aimed to roll back Communism, not merely contain it.

His brainchild became the covert-operations directorate

of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Though Mr. Kennan left the foreign service more than half

a century ago, he continued to be a leading thinker in

international affairs until his death. Since the 1950's

he had been associated with the Institute for Advanced

Study in Princeton, where he was most recently a

professor emeritus.

By the end of his long, productive life, Mr. Kennan had

become a phenomenon in international affairs, with

seminars held and books written to debate and analyze his

extraordinary influence on American policy during the

cold war. He was the author of 17 books, two of them

Pulitzer Prize-winners, and countless articles in leading

journals.

| G.F.KENNAN: Whoever does not understand that

when it comes to nuclear weapons the whole

concept of relative advantage is

illusory—whoever does not understand that

when you are talking about preposterous

quantities of overkill the relative sizes of

arsenals have no serious meaning—whoever

does not understand that the danger lies not in

the possibility that someone else might have more

missiles and warheads than you do, but in the

very existence of these unconscionable quantities

of highly poisonous explosives, and their

existence, above all, in hands as weak and shaky

and undependable as those of ourselves or our

adversaries or any other mere human beings;

whoever does not understand these things is never

going to guide us out of this increasingly dark

and menacing forest into which we have all

wandered. |

His writing, from classified cables to memoirs, was the

force that made him "the nearest thing to a legend

that this country's diplomatic service has ever

produced," in the words of the historian Ronald

Steel.

"He'll be remembered as a diplomatist and a grand

strategist," said John Lewis Gaddis, a leading

historian of the cold war, who is preparing a biography

of Mr. Kennan. "But he saw himself as a literary

figure. He would have loved to have been a poet, a

novelist."

Morton H. Halperin, who was chief of policy planning

during the Clinton

administration, said Mr. Kennan "set a standard that

all his successors have sought to follow."

Mr. Halperin said Mr. Kennan understood the need to talk

truth to power no matter how unpopular, and made clear

his belief that containment was primarily a political and

diplomatic policy rather than a military one. "His

career since is clear proof that no matter how important

the role of the policy planning director, a private

citizen can have an even greater impact with the strength

of his ideas."

G.F.KENNAN:

In the final week of his life, Albert Einstein

signed the last of the collective appeals against

the development of nuclear weapons that he was

ever to sign. He was dead before it could see

publication. It was an appeal drafted, I gather,

by Bertrand Russell. I had my differences with

Russell at the time, as I do now in retrospect.

But I would like to quote one sentence from the

final paragraph of that statement, not just

because it was the last one Einstein ever signed,

but because it sums up, I think, all that I have

been trying to say on the subject. It reads as

follows:

What is necessary is only the overcoming of the military fixations that now command in so high degree the reactions on both sides, and the mustering of great courage by the statesmen in facing up to the task of relating military affairs to the other needs of the modern society. What is needed is that statesmen on both sides of the line should take their military establishments in hand and insist that these establishments should become the servants, not the masters and determinants, of political action. Both sides must learn to accept the fact that there is no security to be found in the quest for military superiority—that only in the reduction, not the multiplication, of the existing monstrous arsenals can the true security of any nation be found. |

The force of Mr. Kennan's ideas brought him to power in

Washington in the brief months after World War II ended

and before the cold war began. In February 1946, as the

second-ranking diplomat in the American Embassy in

Moscow, he dispatched his famous "Long

Telegram" to Washington, perhaps the best-known

cable in American diplomatic history. It explained to

policy makers baffled by Stalin that while Soviet power

was "impervious to the logic of reason," it was

"highly sensitive to the logic of force."

| G.F.KENNAN: I don't think FDR was capable of

conceiving of a man of such profound iniquity,

coupled with enormous strategic cleverness, as

Stalin. He had never met such a creature. And

Stalin was an excellent actor, and when he did

meet with leading people at these various

conferences, he was magnificent: quiet, affable,

reasonable. He sent them all away thinking,

"This really is a great leader." And

yes, but behind that there lay something entirely

different. Charles Bohlen, my colleague who succeeded me as ambassador there, was present at the Yalta and the Potsdam conferences. He told me that he saw only on one or two occasions when the assistants to Stalin had said or done something of which he didn't approve, when he turned on them and then the yellow eyes lit up -- you suddenly realized what sort of an animal you had by the tail there. |

Widely circulated in Washington, the Long Telegram made

Mr. Kennan famous. It evolved into an even better-known

work, "The Sources of Soviet Conduct," which

Mr. Kennan published under the anonymous byline

"X" in the July 1947 issue of Foreign Affairs,

the journal of the Council on Foreign Relations.

"Soviet pressure against the free institutions of

the Western world is something that can be contained by

the adroit and vigorous application of

counterforce," he wrote. That force, Kennan

believed, should take the form of diplomacy and covert

action, not war.

| G.F.KENNAN: I was sometimes surprised and shocked at the enthusiasm with which this telegram was received and the things that I had to say generally -- not just in the telegram -- were received in Washington. And I realize there was a real danger there. I'm sorry that in the telegram I did not more emphasize that this did not mean that we would have to have a war with Russia, but we would have to find a way of dealing with them which was quite different from that which had been going on. |

Mr. Kennan's best-known legacy was this postwar policy of

containment, "a strategy that held up awfully

well," said Mr. Gaddis.

But Mr. Kennan was deeply dismayed when the policy was

associated with the immense build-up in conventional arms

and nuclear weapons that characterized the cold war from

the 1950's onward. His views were always more complex

than the interpretation others gave them, as he argued

repeatedly in his writings. He came to deplore the

growing belligerence toward Moscow that gripped

Washington by the early 1950's, setting the stage for

anti-Communist witch hunts that severely dented the

American foreign service.

At the height of the Korean War, he temporarily left the

State Department for the Institute for Advanced Study. He

returned to serve as ambassador to Moscow, arriving there

in March 1952.

But it was "a disastrous assignment," Mr.

Gaddis said. Mr. Kennan was placed under heavy

surveillance by Soviet intelligence, which cut him off

from contact with Soviet citizens. Frustrated, Mr. Kennan

publicly compared living in Stalin's Moscow to his

experience as an internee in Nazi Germany. The Soviets

declared him persona non grata.

| ON STALIN : You must remember one thing, that Stalin was distrustful, in a pathological way, of anyone who professed friendship or fidelity to him. Those abnormal reactions did not affect the foreign statesmen who came to see him. They had never said that they were partisans of his, and then he couldn't punish them anyway. So he treated them in quite a different way than he did his own people, and some of them fell for this and they were really influenced by it; and I think a number of people came out saying, "Well, this is quite a reasonable man." On how the Cold War affected Stalin's domestic agenda: Stalin felt that in order to get public support for the things he was doing -- which were very harsh policies -- he had to convince a great many of the people, the common people and the party members, that Russia was confronted with a conspiracy on the part of the major capitalist powers: especially England, but Germany too. That they were confronted with efforts by these people to undermine the Soviet government by espionage, by trying to paralyze Russian industry through sabotage, things of that sort. There wasn't any truth in this, but he didn't care: he saw the safety of his own regime being endangered if he could not make people believe that Russia was a threatened country. And so he did conduct these various trials: the Shakhty trial, the trial of the German engineers, the one in which the British appeared as the danger spot. And in doing this, he was deliberately sacrificing, to some extent, the possibility of good relations with these countries, because they were furious about this. This was not compatible with the idea of agreeable diplomatic relations. On the 1937 Soviet purge trials: I attended only one of the three trials. I realized after attending this one and looking over the record which they put out of the three trials, that in these three trials Stalin tried ... to get rid of the people within his own movement who he felt were secretly opposing him. I had enough experience in Russia to know what must have been happening to these men [at the purge trials] who were placed on the dock. I could see them there, and their pale faces, their twitching lips, their evasive eyes. These were the faces of men who had been, if not tortured, then terrified in many ways, and often by threats to take it out on their families if they didn't confess. But they had been through hell, and they knew that these were likely to be their last hours. They were indeed: The same men that we saw standing up there, by the time the darkness fell they were no longer in this world. It was a terrible spectacle. To any of us who knew Russia, we knew that this was a whole contrived event. This was not the trial. The trial had gone on behind the scenes, in party circles and in police circles long before these people appeared on the docket. It is regrettable that the other foreign advisers there -- foreign visitors who were invited to that trial -- that not all of them even understood this. On the Soviet slide into Stalinist terror: It wasn't the [Kirov] murder alone; the murder was a response to something that happened, I believe, in the party gathering that took place in the late summer, I believe, of 1934, in which Stalin was made to realize that there was a real chance of his being voted out of office by the Central Committee. And he, being the brilliant tactician that he was, met this head on, when he realized what was going on and said in effect to them: "Well, you know of course there are people who think it's time that I left. And if that's the view of the body here, why I'd be happy to consider that." Well, he threw terror into all these people because every one of them realized that if he alone got up and said, "I think we should take Stalin at his word and let him go," and the others didn't support him, it would mean his head. So Stalin rode out this, but he didn't get over the shock of it. |

From One Dulles to the Other

Mr. Kennan was then pushed out of the Foreign Service in

1953 by the new

Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, who took office

under the newly elected President Eisenhower. Allen

Dulles, the new director of central intelligence, then

offered a post to the man his brother had rejected -

knowing, as few others did, of Mr. Kennan's crucial role

in the formation of the C.I.A. clandestine service.

Mr. Kennan had argued for "the inauguration of

political warfare" against the Soviet Union in a May

1948 memorandum that was classified top secret for almost

50 years. "The time is now fully ripe for the

creation of a covert political warfare operations

directorate within the government," he wrote. This

seed quickly grew into the covert arm of the Central

Intelligence Agency. It began as the Office of Policy

Coordination, planning and conducting the agency's

biggest and most ambitious schemes, and within four years

grew into the agency's operations directorate, with

thousands of clandestine officers overseas.

A generation later, testifying before a 1975 Senate

select committee, he called the political-warfare

initiative "the greatest mistake I ever made."

Mr. Kennan also played a formative

role in the foundation of Radio Free Europe. Seeking ways

to use the skills of émigrés from the Soviet Union's

cold-war satellites, he asked a retired ambassador,

Joseph C. Grew, to form an anticommunist group called the

National Committee for a Free Europe. Backed by the

C.I.A., the committee set up Radio Free Europe, which

broadcast news and propaganda throughout Eastern Europe.

Two prominent dissidents of their times, Lech Walesa in

Poland and Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia, praised R.F.E.

as highly influential.

Mr. Kennan supported the war in Korea, albeit with some

uncertainty, but opposed United States involvement

anywhere in Indochina long before American troops were

sent to Vietnam. He did not include the region in his

mental list of areas crucial to American security.

In February 1997, Mr. Kennan wrote on The New York

Times's Op-Ed page that the Clinton administration's

decision to back an enlargement of NATO, the North

Atlantic Treaty Organization, to bring it to the borders

of Russia was a terrible mistake. He wrote that

"expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of

American policy in the entire post-cold war era."

"Such a decision may be expected to inflame the

nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic tendencies

in Russian opinion; to have an adverse effect on the

development of Russian democracy; to restore the

atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations, and to

impel Russian foreign policy in directions decidedly not

to our liking," he wrote. His views, shared by a

broad range of policy experts, did not prevail.

Mr. Kennan was the last of a generation of diplomatic

aristocrats in an old world model - products of the

"right" schools, universities and clubs, who

took on the enormous challenges of building a new world

order and trying to define America's place within it

after the defeat of the Nazis and a militaristic Japanese

empire.

| "This whole

tendency to see ourselves as the center of

political enlightenment and as teachers to a

great part of the rest of the world strikes me as

unthought-through, vainglorious and

undesirable," he said in an interview with

the New York Review of Books in 1999. "I would like to see our

government gradually withdraw from its public

advocacy of democracy and human rights. I submit

that governments should deal with other

governments as such, and should avoid unnecessary

involvement, particularly personal involvement,

with their leaders." His concern was that containment had been turned on its head, that an undue emphasis on military pressure rather than diplomacy was increasing the danger of war with the Soviet Union rather than reducing it. He predicted that schisms would appear in the communist camp that could be exploited by the United States. Indeed, Yugoslavia declared its independence of Moscow in 1948. Mr. Kennan wrote that a similar rift would develop between the Soviet Union and China. It occurred in the 1950s. At the same time, he warned against such involvements as the one the United States undertook in Vietnam: "To oppose efforts of indigenous communist elements within foreign countries must generally be considered a risky and profitless undertaking, apt to do more harm than good." In the early days of the Korean War, when the invasion of South Korea had been repulsed, he urged that United Nations forces be kept out of North Korea and that negotiations begin. His advice was ignored.Washington Post obit.March2005 |

With history as a guide, these

worldly-wise policy makers ultimately decided against

punitive policies toward the losers, instead helping the

defeated countries rebuild as democracies. But the

diplomatic establishment had no precedent to fall back on

as they wrestled with Soviet Communism and a Maoist

revolution in China.

Though Mr. Kennan is often grouped among the "Wise

Men" who shaped Washington after World War II, he

did not share their heritage. "He was not part of

the elite East Coast establishment," Mr. Gaddis

said. "He was never wealthy. He worked his way

through college, and he lost all his money in the

Depression. He always felt he was an outsider, never an

insider."

Mr. Kennan was often a gloomy, sensitive and intensely

serious man. Perennially unable to tailor his crisp

intellectual views to political necessity in Washington,

and lacking the political and bureaucratic skills needed

to survive there, Mr. Kennan appeared to those who knew

him to be happy to find a long-term home in Princeton,

where Albert Einstein and other leading thinkers also

honed their ideas.

Ever the Policy Maker

From that perch in 1993, Mr. Kennan recommended,

characteristically, that the United States needed an

unelected, apolitical "council of state" drawn

from the country's best brains to advise all branches of

government in long-term policies. He proposed the council

in a very personal book, "Around the Cragged

Hill" (Norton 1993), which revealed his core social

conservatism as he reviewed the evolution of America.

He fretted that the population of the United States was

growing too fast and that, environmentally, the country

was "exhausting and depleting the very sources of

its own abundance." He blamed cars and the suburban

sprawl they created for the death of not only a

magnificent railway network but also the "great

urban centers of the 19th century, with all the glories

of economic and cultural life that flowed from their very

unity and compactness."

But Mr. Kennan was most preoccupied with society's

effects on making foreign policy, an increasingly

shrunken intellectual field in an age when American

diplomacy itself has been driven to penury by a dominant

new breed of post-cold-war America-Firsters. He saw

American policy by the end of the 20th century as

unfocused, adrift and subject to too many (sometimes

conflicting) domestic political pressures, with a host of

players who have diminished the role of the secretary of

state at a moment in history when the United States stood

alone in its world power.

"It is not too much to say that the American people

have it in their power,

given the requisite will and imagination, to set for the

rest of the world a

unique example of the way a modern, advanced society

could be shaped in order to meet successfully the

emerging tests of the modern and future age," he

wrote in "Around the Cragged Hill."

Among his other well-known works were "American

Diplomacy 1900-1950"; "Russia Leaves the

War," winner of the Pulitzer prize for history in

1957 and the Bancroft and Francis Parkman prizes and a

National Book Award; and two volumes of memoirs, in 1967

and 1972, the first of which won another National Book

Award and another Pulitzer. Mr. Kennan was awarded the

Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor, by

President George H.W. Bush in 1989.

The Modest Beginnings

George Frost Kennan was born in Milwaukee on Feb. 16,

1904, the son of Kossuth Kent Kennan, a lawyer who was a

descendant of Scotch-Irish settlers of 18th-century

America and who was named for the Hungarian patriot. His

mother, the former Florence James, died two months after

his birth.

When he was 8, he was sent to Germany in the care of his

stepmother - his father had remarried - to learn German

in Kassel, because of the purity of the language there.

It was the first of numerous languages he would

eventually master: Russian, French, Polish, Czech,

Portuguese and Norwegian.

Educated at St. John's Northwestern Military Academy in

Delafield, Wis., and at Princeton University, where he

received his bachelor's degree in 1925, he decided to try

for the Foreign Service rather than return to Milwaukee.

"It was the first and last sensible decision I was

ever deliberately to make about my occupation," he

said.

Mr. Kennan served as a vice consul in Geneva and Hamburg

in 1927 and was on the verge of resigning to go back to

school when he learned that he could be trained as a

linguist and get three years of graduate study without

leaving the service. He went to Berlin University and

chose to study Russian, partly in preparation for the

opening of United States-Soviet relations, which occurred

in 1933, and partly because another George Kennan, his

grandfather's cousin, had devoted himself to studying

Russia.

While in Berlin, Mr. Kennan met Annelise Sorensen, a

Norwegian, and they were married in 1931. They had four

children. He is survived by his wife and their children -

Grace Kennan Warnecke of New York, Joan Kennan of

Washington, D.C., Wendy Kennan of Cornwall, England, and

Christopher J. Kennan of Pine Plains, N.Y. - and by eight

grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

| In "Sketches,"

he offered his idea of the typical Californian

(and by implication the typical American):

"Childlike in many respects: fun-loving,

quick to laughter and enthusiasm, unanalytical,

unintellectual, outwardly expansive, preoccupied

with physical beauty and prowess, given to sudden

and unthinking seizures of aggressiveness, driven

constantly to protect his status in the group by

an eager conformism -- yet not unhappy." In "Around The Cragged Hill," he wrote that the United States is devoid of "intelligent and discriminating administration," and should be broken up into a dozen republics. The country should be guided by an advisory council made up of distinguished citizens. Washington Post obit March 2005 |

In the five and a half years between Mr. Kennan's

decision to become a

specialist on Soviet affairs and his first assignment to

Moscow in 1933, he

served in a number of posts on the periphery of the

Soviet Union. He was third secretary in the embassy in

Riga, Latvia, when he was assigned to accompany William

C. Bullitt, the first United States ambassador to the

Soviet Union.

During his career, he was assigned to Moscow three more

times - as second secretary in 1935 and 1936, as

minister-counselor from 1944 to 1946, first under W.

Averell Harriman, then under Gen. Walter Bedell Smith,

and finally for a brief term as ambassador in 1952.

When he was appointed to the embassy in Moscow in 1944 as

minister-counselor, he described his return after a

six-year absence as an unsettling experience because of

the hostility and suspicion he found in the official

circles of a wartime ally.

"Never," he wrote, "except possibly during

my later experience as ambassador to Moscow, did the

insistence of the Soviet authorities on the isolation of

the diplomatic corps weigh more heavily on me. We were

sincerely moved by the sufferings of the Russian people

as well as by the heroism and patience they were showing.

We wished them nothing but well. It was doubly hard in

these circumstances to find ourselves treated as though

we were the bearers of some species of the plague."

Mr. Kennan, convinced that it

would be folly to hope for extensive Soviet

cooperation in the postwar world, was frustrated by the

development in

Washington of what he saw as an increasingly naïve

policy based on notions of

Soviet friendship. He wrote analytical essays, but these

won little or no

attention in the State Department.

It was not until the United States Treasury, stung by

Moscow's unwillingness to support the World Bank and

International Monetary Fund, asked the State Department

for an explanation of its behavior that Mr. Kennan was

able to make his points in the "Long Telegram,"

which arrived in Washington on Feb. 22, 1946. It was so

well-received that "my official loneliness came to

an end," he wrote later. "My reputation was

made. My voice now carried."

Regrettably, in Mr. Kennan's view, the warnings that had

fallen on deaf ears for so long found receptive ones

partly for the wrong reasons, and he felt that the idea

of a Soviet danger became as exaggerated as the belief in

Soviet friendship had been.

| G.F.KENNAN: We had accustomed ourselves,

through our wartime experience, to having a great

enemy before us who had to be considered capable

and desirous of doing everything that was evil

and bad for us. And as our attention shifted then

from Hitler's Germany to what was now the other

greatest military power in Europe, we began to

attach these sort of extremist views to Russia,

too. We like to have our enemies in the singular, our friends, if you will, multiple. But the enemy must always be a center, he must be totally evil, he must wish all the terrible things that could happen to us -- whether [that] made sense from his standpoint or not. ... Carrying wartime extremisms into a period which was nominally one of peace ... is one of the great fundamental causes of the Cold War.......................You must remember my view of warfare: that everybody is a defeated power with modern warfare, with modern weapons. I don't know any more to say about that. My thoughts about containment were of course distorted by the people who understood it and pursued it exclusively as a military concept; and I think that that, as much as any other cause, led to [the] 40 years of unnecessary, fearfully expensive and disoriented process of the Cold War. |

He held that the Soviet Union should be challenged only

when it encroached on certain areas of specific American

interest, but he did not accept the view that this could

be accomplished only by military alliances or by turning

Europe into an armed camp. He felt that Communism needed

to be confronted politically when it appeared outside the

Soviet sphere.

Publicly, he was sharply critical of émigré propaganda

calling for the overthrow of the Soviet system, believing

that there was no guarantee that anything more democratic

would replace it. In the 1960's and 70's, he concluded

that the growing diversity in the Communist world was one

of the most significant political developments of the

century. But "he missed the ideological appeal of

democratic culture in the rest of the world," Mr.

Gaddis said, as the slow rot of Soviet Communism

undermined the cold war's architectures.

The 'X' Article on Containment

Mr. Kennan had returned to Washington in 1946 as the

first deputy for foreign affairs at the new National War

College, where he prepared a paper on the nature of

Soviet power for James V. Forrestal, then secretary of

the Navy. In July 1947, that paper, drawn largely from

his Moscow essays, became the "X" article. The

article, advocating the containment of Soviet power, was

not signed because Mr. Kennan had accepted a new State

Department assignment. But the author's identity soon

became known.

Mr. Kennan was attacked by the influential columnist

Walter Lippmann, who interpreted containment - as did

many others - in a military sense.

In his memoirs, Mr. Kennan said that some of the language

he had used in advocating a long-term, patient but firm

and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies

"was at best ambiguous and lent itself to

misinterpretation." He had failed to make it clear,

he said, that what he was talking about was not the

containment by military means or military threat, but the

political containment of a political threat.

As chairman of the planning staff at a time when planning

still played a large role in policy-making, Mr. Kennan

helped shift the United States to political and

diplomatic containment.

He contributed an overall rationale to a series of

actions like Greek-Turkish aid, under what became known

as the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan and the

creation of the Western military alliance.

Taking an active interest in the

occupation of Japan and Germany, he incurred considerable

criticism by opposing the Nuremberg war-crimes trials,

arguing that the United States should not sit in judgment

with the Soviet Union, where millions had been killed by

their own government.

He also argued against basing American troops in Japan

under long-range agreements, feeling this would

antagonize the Soviet Union, which might feel its eastern

flank threatened.

In 1950, having left the planning staff to become a

counselor to Secretary of State Dean Acheson, Mr. Kennan

was at odds with the State Department over the American

military role in Korea and other issues. He asked for a

leave of absence and moved to Princeton at the invitation

of his friend J. Robert Oppenheimer, who headed the

American development of the atomic bomb at Los Alamos, to

join the Institute for Advanced Studies. He and his

family divided their time between a home in Princeton and

a farm in New Berlin, Pa. Later they added a family home

in Norway.

| Mr. Kennan was the

first analyst to say that nuclear weapons could

serve as a deterrent but could never be used in

war. He was so outspoken in his opposition to

developing a hydrogen bomb that Secretary of

State Dean Acheson said, "If that is your

view, you ought to resign from the Foreign

Service and go out and preach your Quaker gospel,

but don't do it within the department." In 1953, when he returned to the State Department from Princeton, he asked Secretary of State John Foster Dulles what his assignment would be. Dulles replied that he had nothing to offer. A brilliant career thus came to an end. Washington Post obit.March2005 |

After General of the Army Douglas MacArthur was dismissed

by President Truman in 1951, Mr. Kennan was asked by the

State Department to sound out Yakov A. Malik, the Soviet

delegate to the United Nations, about a possible

settlement of the Korean War. Secret meetings took place

between the two men in June 1951- Russian was spoken -

and formal talks leading to a cease-fire followed, a

sequence that, in Mr. Kennan's view, underlined the value

of secret diplomacy conducted by professionals.

| INTERVIEW WITH DAVID GERGEN:Of course, you

came into our consciousness for many Americans in

1947 when you were the author of so-called

containment policy with regard to the Soviet

Union, and yet you write in your book as a

consistent theme that that, that that policy

proposal that you made was misunderstood in our

own government. GEORGE KENNAN, Author, At A Century's Ending: Well, it certainly was, and it's my own fault that it was. It all came down to one sentence in the "X" Article where I said that wherever these people, meaning the Soviet leadership, confronted us with dangerous hostility anywhere in the world, we should do everything possible to contain it and not let them expand any further. I should have explained that I didn't suspect them of any desire to launch an attack on us. This was right after the war, and it was absurd to suppose that they were going to turn around and attack the United States. I didn't think I needed to explain that, but I obviously should have done it. DAVID GERGEN: Well, you intended then to have political containment-- --of the Soviet Union, not military containment. GEORGE KENNAN: Exactly. And I was moved to this largely by what was happening in, in Western Europe, but also what I have been able to observe, serving in Moscow until 1936, through the final two years of the war-- |

Mr. Kennan's entire career had

seemed to be preparation for his 1952 appointment as

ambassador to Moscow, but his tour ended after five

months when he was declared persona non grata - on

Stalin's whim, he thought - for a chance remark to a

reporter in West Berlin who had asked him what life was

like in the Soviet Union. He drew a comparison to his

imprisonment earlier by the Nazis, adding, "Except

that in Moscow we are at liberty to go out and walk the

streets under guard." Left in limbo by the State

Department on his return to Washington, and with policy

disagreements growing between him and Secretary of State

Dulles, who viewed containment as too passive, Mr. Kennan

retired from the Foreign Service in 1953. This difficult

period was made even more painful by McCarthyism. Many of

Mr. Kennan's old colleagues and friends - among them

Professor Oppenheimer, John Paton Davies, John Stewart

Service and Charles W. Thayer - came under attack. He

testified repeatedly in their defense and wrote and spoke

against what he termed the malodorous tide of the times.

During a pleasant academic year

in 1957-58 as Eastman professor at Oxford, he was invited

to deliver the BBC's annual Reith Lectures, radio talks

to which all intellectual Britain is attuned.

A Surprising Offer to the Soviets

He attracted great attention by

proposing that the time was right to begin

negotiating with the Soviet Union for mutual troop

withdrawals from Germany. It was an idea acceptable to

only a small body of left-wing opinion, as was his

further suggestion that the demilitarization be achieved

through the guarantee of a neutral, unified Germany. His

views came under immediate fire all over Western Europe

and in North America.

Called back into government service in 1961 by President

John F. Kennedy, Mr. Kennan was named ambassador to

Yugoslavia and became embroiled in arguments over the

proper role of Congress in foreign affairs. He sought

unsuccessfully to dissuade Mr. Kennedy from proclaiming

Captive Nations Week in 1961 - as required by a

Congressional resolution of 1959 - on the ground that the

United States had no reason to make the resolution, which

in effect called for the overthrow of all the governments

of Eastern Europe, a part of public policy. The next year

Congress voted to bar aid and trade concessions to the

Yugoslavs, so Mr. Kennan felt he could no longer serve

usefully in Belgrade.

In 1966 Mr. Kennan, who had returned to Princeton in

1963, was called to testify before the Senate Foreign

Relations Committee on the Vietnam War, an American

involvement he felt should not have been begun and should

not be prolonged. In 1967 he took part in a Senate review

of American foreign policy.

For Mr. Kennan the Vietnam years were what he later

characterized as instructive. His views on what he saw as

almost entirely negative Congressional interference in

foreign affairs altered as Congress moved to curtail the

American role in Southeast Asia, an area where he

believed the American interest was not at stake. In an

interview at the time of his 72nd birthday, he said that

he had been "instructed" by Vietnam, and that

he now agreed that Congress should help in determining

foreign policy. He added that given that reality, the

United States would have to reduce its scope and limit

its methods because Congressional control of foreign

affairs deprives the Government of day-to-day direction

of events "and means that as a nation we will have

to pull back a bit - not become isolationist, but just

rule out fancy diplomacy."

Opposed though he was to United States involvement in

Southeast Asia, he was critical of the student left in

the 60's. In a speech at Swarthmore College in December

1967, he assailed the students' methods of protest and

their failure to present a coherent program of reform.

| G.F.KENNAN: One sometimes feels a guest of one's time and not a member of its household. |

Later in life, Mr. Kennan turned his attention to support

of Russian and Soviet

studies in the United States, feeling that scholarship

was one of America's most

productive links with Moscow. "They are impressed by

our work," he remarked in

an interview. "It keeps Russian intellectuals from

thinking we are all a nation

of flagpole-sitters."

| G.F.LKENNAN: Not only the studying and

writing of history but also the honoring of it

both represent affirmations of a certain defiant

faith - a desperate, unreasoning faith, if you

will - but faith nevertheless in the endurance of

this threatened world - faith in the total

essentiality of historical

continuity................................The

very concept of history implies the scholar and

the reader. Without a generation of civilized

people to study history, to preserve its records,

to absorb its lessons and relate them to its own

problems, history, too, would lose its meaning. |

In 1974 and 1975, while in Washington as a Woodrow Wilson

scholar, he helped to

establish the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian

Studies in the Smithsonian

complex. Recalling the ancestor who led him to study

Russian, he said, "When my

colleagues gave it a name, they had in mind both George

Kennans."

| "War has a

momentum of its own, and it carries you away from

all thoughtful intentions when you get into it.

Today, if we went into Iraq, like the president

would like us to do, you know where you begin.

You never know where you are going to end,"

warned Kennan. From U.S. Department of State, International Information Programs, September 27, 2002 In the interview, this 98-year-old diplomat and historian praised the diplomacy of Secretary of State Colin Powell, whom he called a man of strong loyalties in a difficult position who has been much more powerful in his statements than the Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld. |

| .G.F.KENNAN....one of the

things that bothers me about the computer culture

of the present age is that one of the things of

which it seems to me we have the least need is

further information. What we really need is

intelligent guidance in what to do with the

information we've got.....we look for general

policies, very sweeping policies-- --in the

world. And that isn't the way international

affairs work. We ought to look at every problem

on its own merits. .....................I see

groping on the part of our people today. They

say, well, the Cold War is over, but what's going

to become the worldwide basis of American foreign

policy now?.... And they don't realize you can't

confront it that way. This is a big world. It's a

developing world. It's not a static world. It's

full of different forces contending with each

other. And we have to look at this every day and

say what is in the first place in the interests

of this country, but secondly, what is in the

interest also of world peace and stability?... I

would say that the--you do have a possibility of

a global national interest that is in the

environmental theater, and we should do all we

can to try to convince ourselves and the rest of

the world that we've got to stop abusing the

environment of this whole planet. It's not just

one person's, one country's problem. It's a

universal problem today. That I feel very

strongly about. Also, I think that we should

recognize ourselves and should try to persuade

others that war among great industrial developed

countries in this age has lost its rationale.

Nobody can win by it. The destructiveness of

weapons is such that there are only losers out of

any attempt to settle greatly the national

problem by force-- I think the effort to extend NATO to the borders of Russia is really a mistaken policy, a very dangerous policy and unnecessary. (FROM INTERVIEW WITH DAVID GERGEN.) |