FEBRUARY/MARCH 2006

Interview with Ibrahim Issa at the Hope Flowers School

Please tell me a little about yourself and how you became involved in peace work?

I was born in Deheishe Refugee Camp1 and spent 8 years in the Deheishe Refugee Camp with my family until I went to Bethlehem. My family bought a house there and we lived in Bethlehem. Then I lived in the Netherlands; I studied mechanical engineering there. I have my Masters of Science degree in mechanical engineering. In the year 2000, my father, the founder of Hope Flowers School,2 died. There was a vacuum, especially in the school, after the beginning of the intifada. So it was a matter of priorities whether to continue living my comfortable life in the Netherlands or to follow my commitment to peace education here. So in the year 2000, I decided to return from the Netherlands to engage in the work that I’m doing now. Maybe my commitment to peace education and to following in my father’s footsteps, which I find very important, is the reason I’m doing this work.

Where was your family from, before Deheishe?

Well, my father was born in Ramle,3 in the north part of Palestine, which later on became Israel. His family’s properties were all confiscated in the war in 1948 and they were forced to live as refugees in Deheishe Refugee Camp. My grandfather died in 1949 because he was heartbroken. He lost everything and had nothing left. He couldn’t imagine life as a refugee. So he died in 1949, and my father faced huge emotional and psychological problems at that time. He tried living in the refugee camp with his mother and three sisters. His mother was an illiterate woman and as a child he worked to support his family. He started his education when he was nine-years-old. This background was the driving force for Hussein [Ibrahim Issa's father] to found the Hope Flowers School.4

Everyone’s mood at that time was to resist the occupation. Hussein believed in freedom but he saw that violence brings only violence. What we need is to create a new generation of Palestinians and Israelis who believe in peace, coexistence and respecting each other’s rights. This was the way he saw to bring about change and to gain freedom as Palestinians. The non-violent model was his main vision. Before founding the Hope Flowers School in 1984, Hussein was a non-violent activist since the 70’s. His vision led him to establish the Hope Flowers School, which began as a simple kindergarten.

What did your father do as a non-violent activist?

He was very much involved in raising awareness about non-violence, and what non-violence means. This was one thing. And the other thing I forgot to mention is that Hussein later studied to be a psychologist. He worked with refugees at the United Nations Relief Work Agency for the Palestinians, and during his work with the UNRWA5 he recognized the suffering of Palestinian children and their need for a safe environment, and also the need to protect these children from being involved in violence which would lead to more suffering. So being a non-violent activist for him was also about dealing with these children, teaching people to educate their children to live their lives in peaceful ways. This is what I mean by "non-violence activist".

So sometime during Hussein’s work with UNRWA he recognized his own suffering as a child and as a refugee and then he formulated his vision of nurturing this generation of Palestinians and Israelis. The idea of the school is a pretty simple one. Hussein thought if he could bring Palestinian and Israeli children together, give them a chance and educate them to move beyond fear and stereotypes, then we'd create a generation of children who could grow up together in friendship.

How did your father go about trying to fulfill the goal of educating Israeli and Palestinian children to co-exist?

Well, first he started with the al-Amal elementary care system, which was the kindergarten. Al-Amal means hope, because the school vision was hope. No one in 1984 ever thought about peace and coexistence. Everyone’s mood was against the occupation, and Hussein was also against the occupation.6 But he sought to transform from occupation to freedom in non-violent ways. So he started to organize workshops just to bring these children together, from Israeli and Palestinian kindergartens.

Did the parents come with the kids during visits by Israeli students?

Yes. There were events: sometimes for a day, or a project that spanned the entire year. Later on there were student and teacher exchanges. All of them were joint activities.

He brought Israeli children from kindergartens to the school in El Khader?

Yes. 1984 was the beginning of this.

How did he get Israeli parents to agree to bring their children here?

There was a lot of criticism of that, a lot of critics among the parents and critics from the community and the society here. It wasn’t an easy task. But there was always a minority that was willing to do it, and Hussein encouraged this minority.

Did he choose a particular Israeli city to do school exchanges with?

No. We see all Israelis, except settlers,7 as possible partners, if they have the will to work with Palestinians. And we work with Israelis who are willing to see change here and support the peace process.

How old were you when the school first started?

When the school started as a kindergarten I was finishing my primary education. I was 12 years old.

Were you around? Were you involved in the school when you were younger?

I was around but I wasn’t involved as a student but as an observer.

What did you think of what they were doing when they first opened the school, when you were 12?

It was very exciting as a child. But you know, it was horrible sometimes because there were some attacks by radicals on my family and on my father. As a child I couldn’t really comprehend what was going on. For example there were several times when Palestinian radical groups threw Molotov cocktails at our home, burned the school bus, burned my father’s private car, and tried to attack my father. So as a child, that peace vision was also combined with horrible experiences, and it’s not only from the Palestinians. Later it was from Palestinians and Israelis. In both societies there are radical groups and people who don’t like to see any kind of settlements-- peace settlements.

When you were younger and were seeing all these things, like radicals throwing Molotov cocktails at your house, did you ever wonder why your dad has to do these things?

Well, the most painful thing for me as a child at that time was that I couldn’t recognize the difference between a peace activist and a collaborator;8 it took me years until I did. And this is something that Palestinian radical groups also couldn’t recognize, the difference between collaborators and peace activists. I was a child at that time but when I grew up I started to recognize the difference. Let me say, some of the things we’re doing now are much easier than when my father started.

What had changed when you came back to Bethlehem during the intifada?

A lot of things. First, you have fear, you have daily fear. I mean there are shootings, there is violence here. This is one thing. The other thing is you come up with a plan for your future... there [in the Netherlands] I could easily plan, “I want to do this, I want to achieve this, tomorrow I am going to do this.” I had an agenda there, for example, but I don’t keep one here, because an agenda here is a luxury we don’t have. Everything is a mess here. So to find some order in this country is very difficult. And it is also difficult to live without any hope. You don’t know where you’re going, you are just moving with the stream: moving in the stream of violence, you are just moving with the bad economic situation, you move in the stream of culture, sometimes the tight culture, I mean the very conservative culture. We have a lot of ideals. For me personally I wish to see a school for Palestinians and Israelis, but this, for example, is not realistic at this time. You know, there are limitations. Many things changed.

You say "some things are easier at this time." Why is it easier now?

Because of the awareness now. People can differentiate between collaborator and peace activist. There are many NGOs [non-governmental organizations] in Bethlehem who practice non-violence in the world. And people can easily recognize now what non-violence is, while in 1984 no one recognized what non-violence was. Even if people saw it as threatening; for example in 1984-1985 when the Israelis deported Dr. Mubarak Awad,9 who was the leader of non-violence here—that showed that Israelis could recognize the effect of non-violence as well.

And when you decided to come back how did that feel?

Well... For me, the personal connection, my private life and everything around me was Dutch, my friends here call me ”Dutch,” the Dutch accent, the “Dutch” frame of mind, you get very much connected to the country, to the people. You know, my whole life was there and it isn’t easy to return from something you had in your hands, and then come here. I mean, it was the intifada. Why go into the mess?!

Can you tell me more about Mubarak Awad [Palestinian non-violent leader in the 80s] and what he did?

Actually I don’t know a lot about him. But he created the Palestinian non-violence center, and I think that was the first non-violence center here in Jerusalem. And one or two years after, the Israelis deported him to the USA. He was also a Palestinian-American. He was a close friend of Hussein[my father]. I also think this is one of the reasons why Hussein got so involved with non-violence. He also worked with these people. But the man was deported. I don’t know many other details about him. But non-violence is also a very effective way of resisting the occupation here.

When did the exchanges with the Israeli students stop happening?

After the intifada, the second intifada. Essentially September 2000 was the end of joint activities, and we started to organize joint activities in a third country. Because doing that here is impossible and threatening—it’s dangerous, but also because of logistical problems, the regular closures here, and the transportation [issues]. The Israeli army at the checkpoints prevents any Israelis from coming to Palestinian areas and prevents Palestinians from going to Israeli areas. I have written to Israeli officials, many times, urging them to give permission for such initiatives. And they refused. Why? Because of "security reasons." I think that in times of conflict like this, we need to intensify our contact and come together instead of splitting from each other.

What are some of the largest obstacles you face from within the community itself right now?

Well, there are several obstacles. I’ll speak first about the road closures. We have lost 300 students because they come from villages in the neighborhood here, and after the intifada all roads and all Palestinian cities and villages became isolated from one other. They have become like islands, there is no connection. So we have lost 300 students. And the economic situation: sometimes the school is unable to pay the salaries because people can’t pay the tuition fees. Since 2000 we have had to depend on donations. Another one of the main obstacles here is security. We are now located in “Area C” [under complete Israeli military control]10 and our school received a demolition warning from the Israeli army two months ago for the school cafeteria. So there are several obstacles.

Can you tell me more about that demolition order on the Hope Flowers School cafeteria? Why did they give that order and what are you doing to fight it?

Well, this is not the first demolition warning. In 1999 we received the same warning and after a long process in the Israeli military court in Beit El, the demolition was cancelled, and we applied for a building permit. So far as I know, it was approved. The problem was then the financial problem; we couldn’t afford the Israeli fees for the building permit. It was so hard and we were waiting for the area to be transferred to the Palestinian Authority, to be transformed from “Area C” [under Israeli control] to “Area A” [under the control of the Palestinian Authority] and the building permit fee there is much lower. That was a very optimistic idea in 1999 because in 2000 the intifada started and Area C became Area C plus.11 It’s very complicated. And in November 2003, we received another warning saying the building was built without a permit. But when we looked through the plans we saw that the Israelis are planning to build the security fence—or the segregation wall—here nearby.12 So the maps are not clear. Whether they are going to build it on this side to isolate the school from the Palestinian students, or to build it down the hill and demolish the cafeteria building, is not clear for us. So we think that the demolition now has to do somehow with the security fence that the Israelis plan to build here. Especially because Efrat is expanding; we face the settlement of Efrat, which is some 300 meters from here. We have started a legal process and we are asking all our friends to protest to the Israeli government against this decision.

Who do you think would have the biggest influence on the Israeli government to reverse the demolition order on the cafeteria?

Well, I think US officials. And we wrote many letters to Israeli peace activists and you know, we shouldn’t neglect the role of ourselves as peace activists, not only in Palestine but also all over. Everyone is participating and everyone is very important. I say to everyone, let your voice be heard here.

Can you say more about what you teach in this school?

We have peace and democracy education here. And peace

and democracy education is not given in theoretical

terms, it’s integrated within the school’s

curriculum and extracurricular activities. For example,

we are teaching Hebrew to minimize fear and prevent

stereotyping. We see Hebrew as a way to create contact

between Palestinians and Israelis, to encourage the

contact. By the way, we’re the first Palestinian

school that started to teach Hebrew in 1990. And in 1990

a local Palestinian group burned the school bus because

they found us teaching the language of the occupier. That

was the motivation for burning the bus. In other words,

we’re marketing the language of our occupiers.

The other program is that we teach inter-faith. Normally

in public schools in the area they split the Muslim and

Christian students up from each other, each follows his

own religion. Here we keep the students in the same class

and we teach the effects of the religion, we teach them

how to use religion to bring people together instead of

splitting people apart from each other. We have a program

of promoting inter-cultural understanding, we have

volunteers and we have a volunteer tradition. We have an

Israeli volunteers program, and you have to imagine that

in the volunteers’ program we have Israeli

volunteers teaching Hebrew and Israeli Jewish Rabbis

teaching interfaith, and Christian ministers and Muslims

also. Now we do not have Israelis anymore, but we make

use of our international friends, like Jewish Americans

and European Jews.

How would you respond to the assertion that "teaching Hebrew is marketing the language of your occupiers"?

It’s not that we answered, rather the community answered. Now most of the schools in the Bethlehem area teach the Hebrew language. Most of the bible schools teach the Hebrew language. And you know, we also have a very popular thing here [in our school], which is translation from the Israeli newspapers, and it really depends on language. Actually it’s a method of communication. And the people really appreciate it. If you see people’s responses to this program, we teach French and English also in the school and the response to Hebrew is that it is like a necessity here. So this is one program.

The Jewish Americans and Europeans teach Judaism?

Yes, and the tradition. Inter-faith is very important. There are also extracurricular activities. For example, we teach farming and we are building a mini-farm here for education and income. In 1999 we had a project called The Traditional Farming Project with an Israeli school where we asked the children to create a mini farm, to build a farm together and plant vegetables and wheat and share the yield. That was a very interesting project. That lasted for 2 years and was a huge success here. There are also other levels. We teach 3 levels of peace education here: first, for the teachers, then for the parents, then the students. And so far I have only spoken about the students.

Tell me more about what you do with the parents and teachers.

That’s a lot of information! Look, most important is to prepare the environment here. Peace education is about creating a safe space for the children, and it’s not only for the students but everyone involved: parents, teachers, students, family, all people who are involved. So we start with the teachers here. All our teachers are loyal to the school philosophy because you can’t face peace in conflict. They are, in other words, peace activists. They really support the school’s philosophy. We provide training for our teachers also, on the empowerment theme, compassionate listening and special training on how to deal with the students during times of fear and distress. We involve our teachers in joint projects with international schools. We have many partnerships in Europe, in the US, and in Israel itself. For example, in August 2004, this August, we are planning to start a program with the Israeli Institute for Democratic Education13 to create a network of democratic educators for peace. This is the title of the project where we bring 15 Palestinian and Israeli educators to England for 2 weeks for training on how to establish schools for democracy and how to run democratic schools, but also to encourage peace and understanding peace in the students in their classes. So this is one form on the teachers’ level.

The second level is the parents, because we try to prepare the whole environment in the home as well as in the school, and here I have to mention we don’t prepare the whole environment because the society outside is different. But we’re trying to make that connection between school and family. So we provide the parents with training, and we have, for two years now, psychological support for the children and for the families. We believe here that every act of violence is the result of an unhealed wound. And in order to prevent violence we have to get deeper to the wounds. And this is also a psychological process.

About the teachers, what happens if there are things they don’t like, things they don’t want to participate in?

Well, we don’t hire a teacher just for education

here. There are other schools for that. It’s really

clear from the beginning what we’re hiring them for.

But what if they’re already employed and then you come up with this subject and they say, I don’t want to participate.

Well, we have to know the reason. I mean, maybe it’s for practical reasons, but if it’s from ideological reasons they don’t want to participate because it’s not the work they are willing to do and they are opposing the philosophy then I think that Hope Flowers isn’t the place for them. This is also very clear in our contract.

What if there is something the parents don't like that the school is doing?

Well, we speak to the parents, and we encourage them. If a parent says, no I don’t want to, then we talk to him. And here in many cases we don’t have a problem with the parents.

Do you ever have any doubts about confusing the kids with the reality you have inside the school--- what you teach them ---and the reality they see outside?

We should be very idealistic here; the children are a special part of the outside environment. What we’re doing here is giving them space to feel psychologically and physically safe. And this is the basis of peace education. So you know, a problem they face is the impact of the environment on the children. For example, the reason for founding the psychological support program is that a lot of the students started to come with fear, hyper-activity, aggressiveness, lack of sleep, nightmares, all these symptoms. And there’s psychological stress and you have to deal with that.

Are people in the community still accusing you of "normalization"? You said it’s easier now.

Normalization is a different story; it’s not peace education. And I think many people don’t really know what peace education is, and what normalization is. You know, before getting to normalization you have to have peace. And we don’t have peace, so how can we normalize?

What do you think people are afraid of, when they think about what you’re doing and react badly to it or they have doubts about it?

We shouldn’t think about feelings that “Hope Flowers” is a mysterious thing; most of our peace education programs are devoted to the human himself. Because the essence of peace education is that peace starts inside yourself. So if you link the “Hope Flowers” school to Palestinian and Israeli peace making, that’s only one part of it. I see it as a result. Peace starts with yourself, and this is how we are participating in creating happy human beings. For example, we have a summer school and we’re going to create “Peace Trees Bethlehem,” and this is devoted to peace education within the Palestinian society. And this is also very important. What about the Muslim-Christian relationships in this country as well? Peace education is also needed in this country for the Palestinians themselves, not only for the Palestinians and Israelis. So peace starts with yourself, and this is the main idea. In the summer school we’re creating awareness about the problems in the society and we’re looking for solutions, introducing new solutions and alternatives. One of the problems we are addressing is that people don’t have enough awareness of the importance of a clean environment, for example. Our students and international students are going to plant trees, clean the streets, plant trees and flowers in the streets. This is combined with an awareness campaign in the village. If we make this 1.5 km we’re speaking about a unique example for a clean and peaceable city, and this is something that doesn’t have anything to do with normalization, doesn’t have anything to do with peace--it’s just being devoted to our community.

Do you see successes in your students? Can you describe what you see?

Sure. What was very beautiful to see last year was a group of students who learned about and were speaking about compassionate listening and they were starting to ask whether there was other advanced training. That group studied here, they had their university degrees, but came back asking for programs and training, so we started empowerment training, and now there’s a follow-up for that training. This is all very beautiful to see. But also the role of the students, the leadership they are taking is also very remarkable. Leadership is a very important factor here in the school.

What do you mean by leadership? How do you create a leader?

Well, in my opinion, it starts with the child’s empowerment here in school. Also getting to your inner self, knowing exactly what you need and what bothers you, and what you want and what you don’t want. But also to feel your inner fever that you are free to choose and free to take responsibility, and taking responsibility is the most important thing in empowerment. You have to find what you want and what keeps you from achieving your goal and what kind of beliefs you have for that. And then to go ahead, you decide you want this change and you go ahead with it.

So you have former students who have graduated from university. What do you see some of them doing right now?

Last year a group of all the graduates went to Germany. I think they were mixed - management and business administration, lawyers, and not all of them have university degrees. One of them I think has a business; he is a carpenter, I think. But this is important. What is important is the leadership. As I say not all of the people are doctors and engineers and lawyers, but it’s also important to be a self-leader, that your power comes from yourself not from your position. If the power comes from your position, as soon as that position changes you have a problem. But when it comes from yourself there is something behind it.

What would be the ideal thing that you would hope that a graduate would go and accomplish?

For me it’s leadership again. Believe me, this is like a belief for me, our problems, not only Israel-Palestine but worldwide, we have leadership problems. And if we can create leadership we will solve many, many conflicts.

If you could generalize, is there something that keeps people from achieving what they want to achieve?

The general situation here, I think is bad. I think a lot of people are living their lives without hope, in despair. I recognize that in the young people here this is very dangerous because a person living life without hope and, despair can easily make a wrong decision. So I think the general situation is the main limitation for exploration by these young people.

How has working here changed the way you live your life?

Well, I have very little free time… I have large quantities of work here, and you know you have to deal with expected and unexpected problems. Like two months ago, since November, we have dealt with the demolition order and its very serious effects! And it’s not because it’s a building, but because how can they do that to the only school in the West Bank and Gaza for peace and democracy education? How can we tell our people and speak of success if even the Israeli government is going to destroy that building? So here it’s a matter of survival, so you want to do whatever you can to protect the building but also nonviolently. Because that’s very important.

Do the kids in the school know what’s going on with the Israeli army's order to demolish the cafeteria?

We inform them as part of the democratic education

here where the student council and the students have to

discuss their problems and find solutions for them. This

is part of the empowerment course we are using,

integrating empowerment into education. We told them, but

some problems the students can’t do anything about

it. This is adults’ work and we have to do it.

How do you help them to deal with anger about it?

Our teachers are experienced and trained to deal with these situations, and they normally encourage, we encourage them to speak to the angry student, that students should express their feelings. In times of real crisis we give 20 minutes of the class, of the lesson time, for this issue, but also we have extracurricular activities and physical training is really an important thing here. Being physically active is also a way to get rid of this stress.

How do you deal with news here or with daily events? For example, you’re very close to Deheishe, and if there’s somebody who’s injured, or if a bomber comes from Deheishe, how do you deal with that in school?

I deal with it in two ways. It’s the person here who committed the suicide bombing but also the Israelis shooting, causing distortion of the safe environment that is the essence of peace education. Again, there’s distortion. We speak to the students about their feelings, what they feel. You know, the idea is not for us to tell the students, “don’t hate the Israelis.” This is not the way peace education works. Because that will create resistance and there are many things. But also with adults it’s not that you teach, “love this one and hate that one,” that doesn’t work. It’s important in our work, also with adults, to let people have knowledge, not to make people change; this is collaborative. Because as soon as you force people to change that will create resistance and things will become more complicated. But if you speak to people to foster knowledge, people will change. And this is the essence of compassionate listening, because compassionate listening also means encouraging people to listen--helping people to listen and to specify the underlying needs of a conflict. This is also to collaborate with people. This is also something we do with the students.

Two years ago we had a visitor here, maybe 1 1/2 years ago, who spoke to a child four-year-old and he asked him if he likes the Israelis, and he [the child] said, “no I hate them.” And the visitor said, “how could the child say that in this school!?” I said, “it’s fine, the child is here just a few months and his father is unemployed, was shot by the Israelis and his neighbor’s home was, just a few days ago, demolished. So what do you expect from this child? To jump and say, give me a hug?” That’s not the way we teach here.

It must be hard these days because you can’t actually have a dialogue because you can’t physically get the other side here.

We’re working on that. We are creating computer labs with Internet connection so that the students can communicate with each other through the Internet.

Which school are you working with to set up the Internet communication project for students?

There are several potential schools; our traditional partner schools, that we always work with. But because this project is still new, we’re trying to work with the Democratic School of Hadera,14 maybe the Adam School15 in Jerusalem. We’re still trying to make contacts because the center is not ready yet.

How about the rest of your family, how do they feel about this work?

Well, some people respect, some are conservatives, you can’t generalize.

Do you have other family members who work in the school?

Yes, yes. There is my mother, she is co-founder of the school, and there’s my sister, she’s now on maternity leave. She’s also the English teacher here in the school. But we’re still three family members among the 16 staff members here.

What are the most significant ways this conflict has affected your life, personally?

Well, my home was partially demolished, I was in

prison, I was shot…

Could you tell me more about all those things?

Probably the worst was last year, when I was jailed and my home was demolished. I rented an apartment, a basement apartment in my home, to a Palestinian and he seemed to be wanted. After the Israelis arrested him they arrested me, accusing me of harboring a wanted person, and started to demolish my home. After 5 days I was released and the Israeli army admitted that they made a mistake.

They made a mistake in arresting the wanted man?

No, in jailing me and demolishing my home.

You were shot. What happened?

Well, that was in 1989. It was the first intifada and it was at a demonstration and I was shot.

You were at the demonstration?

Yes. That was during the first intifada. I was a child

and it was what a child can do, throwing a stone.

Do you participate in demonstrations now?

No. I’m a non-violent activist. Well, I participate in demonstrations but not in violent demonstrations. I participate mainly in demonstrations urging peace and understanding to create contact.

How did your father feel about you participating in a demonstration, throwing rocks?

Well, he was very much concerned about what happened to me because I was arrested immediately after I was shot.

Did you get any treatment after you were shot?

Yes, I was shot at like 5 o’clock in the morning and at 4 o’clock in the afternoon I saw a doctor from the Israeli army and he refused to keep me in prison and at 12 o’clock at night I was released.

Where were you shot?

My back.

Were you injured badly?

Yes. For the first four months, my right leg was identified as dead. It took me four-five months before there was any sign that I could use it again.

You say children don't understand what the conflict is about, but when you were 16 you must have known enough about the conflict to be demonstrating…

Yes, exactly. But you don’t know for example that you could have a useless leg. You deal with that, and if the doctor says the future will be good then you take this as in the future I’ll walk again! If your father says, it will be ok, then you think, the whole time that things would be ok. But I was a lucky person because I walked again and other people really couldn’t do that.

How old were you?

I was almost 16. You know, at that age --if that happened now I would be scared to death, but at that time, as a teenager-- I mean the fear and concern and what will happen in the future--I don’t know that I knew these terms at the time. What really bothers me with this conflict is there are many young people, children, killed. And these children don’t really know the difference between Israeli, Palestinian, Muslim, Jew, Christian. And there are innocent people from both sides. They don’t even know anything about the conflict. It’s an adult’s game; it’s adults who understand that.

So you followed your father’s footsteps and you continued working in the school, so what led to this change, was it to honor your father’s memory? Any personal reasons?

Yes, you grow up; you have another perspective on life, and the whole thing. You’re not thinking any more of the little things as a child of 15-16 years old. Now I’m an adult, and I have my own experiences and I can judge what’s right and what’s wrong. And you know when I was here, honestly, I didn’t really appreciate what my father did because I couldn’t understand it. When I was in the Netherlands I could have my own experiences also, and I started also to seek conflict resolution training there and I did that for 9 years. I was active in that. And I went to Serbia, in the war in Yugoslavia, I was in Germany several times, and in Europe, just for these trainings, and I began to develop my personality. Also, to learn more about leadership, and to learn more how to connect with myself, which was very important. So after all this I was planning to continue my PhD and then came the very difficult decision to go ahead and work for the PhD and be a doctor of mechanical engineering, which was a dream for me. I had to follow my feelings, and for me both were very close to my heart, but I had to make a decision, and that decision wasn’t the decision of one day. It took me almost a year to decide.

What do you feel you gained from all this?

Well, I’m more confident. I’m happy, I’m satisfied with everything I’m doing now. I’m doing it with a huge measure of love and patience. I really enjoy that.

What’s the most important thing for you to achieve for yourself and for your pupils?

Well, again, it’s our mission here. We summarize our work here in three words: peace, freedom, education. And our aim here is to create a generation here who lives entirely in democratic freedom with our neighbors. And this is what we want, to be free like all the other people in the world. To participate in creating this generation.

Notes

We have done our best to provide accurate, fair yet succinct footnotes to help you navigate the interviews. Our research team comprises more than 6 individuals, including Palestinians, Israelis and North Americans. Still, we recognize that these notes cannot capture the full complexity of this contested conflict. Therefore, we encourage you to seek additional sources of information, we welcome your feedback and appreciate your openness.

Dheisheh Refugee Camp Immediately west of Bethlehem, the camp is roughly half a square kilometer, and home to about 11,000 Palestinian refugees and their descendants who were expelled or who fled from their homes in the War of 1948. For a brief profile of the Dheisheh refugee camp see UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees) at http://www.un.org/unrwa/refugees/westbank/dheisheh.html. 1

Hope Flowers School is a Palestinian school in El Khader, in the south Bethlehem area of the West Bank (Palestine), dedicated to education for coexistence, peace, non-violence and democracy. (source: http://www.hope-flowers.org/) 2

Ramle A city in the central region of Israel. Est. population 60,000 Jewish and Palestinian Arab-Israeli inhabitants. 3

For more on Ihabrim Issa’s father Hussein Ibrahim Issa, see http://www.hope-flowers.org/founder.html. 4

UNRWA The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East is a relief and human development agency of over 25,000 staff serving the four million Palestinian refugees in the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, Jordan, Lebanon and the Syrian Arab republic. (source: http://www.un.org/unrwa/) 5

Refers to the Israeli military occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, home to 3.5 million Palestinians. 6

Settler Refers to a Jewish Israeli living in settlements - Jewish communities in the West Bank or Gaza Strip. The settlements, established following Israel’s capture of the West Bank and Gaza Strip in the war of 1967, are widely recognized as illegal under international law. By and large, they receive government funding as well as military and infrastructural support, although the Likud has initiated the withdrawal of settlers from Gaza in August 2005 and from a handful of settlements in the West Bank. Population statistics of the Jewish settler population vary according to different sources. There are approximately 240,00-250,000 settlers in the Palestinian Territories with approximately 7,000-8,000 living in the Gaza Strip and the rest residing in the West Bank (excluding East Jerusalem). According to B’Tselem, at the end of 2002 about 58% (or 394,000) of Jerusalem’s 680,400 residents lived on land annexed in 1967. Of those 394,000, 45% were Jewish and 55% Palestinians (see http://www.btselem.org/English/Jerusalem/). There are approximately 17,000 settlers living in the Golan Heights. For information on Israeli settlements in the West Bank, see the B’Tselem report at http://www.btselem.org/English/Publications/Summaries/200205_Land_Grab.asp. For information on the settlement population in the Golan Heights see: David Rudge. “Campaign Uses Jobs to Entice Newcomers to Golan,” The Jerusalem Post, 22 June 2005, pg. 5. 7

Palestinians known or accused of colluding with Israeli occupation forces. 8

Mubarak Awad A prominent advocate for non-violent resistance to the Israeli occupation, Dr. Mubarak Awad was deported to Washington by the Israeli government in 1988. He is currently Adjunct Professor of International Peace and Conflict Resolution at The American University in Washington, D.C. 9

The Israeli-Palestinian Oslo accords divided the Palestinian territories into three distinct zones: “Zone A” under full Palestinian control, “Zone B” under Palestinian civil control and Israeli security control, and “Zone C”, under full Israeli control. 10

Area C of the West Bank is under Israeli Military Control. Issa's comment about Area C plus was made in jest. 11

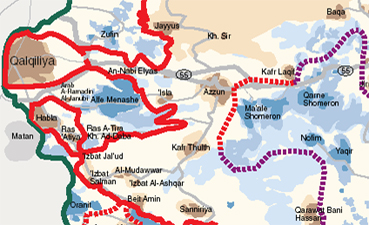

The Wall A long structure of

connected concrete walls and fences that separates Israel

from parts of the West Bank. It runs both along the Green

Line and within the West Bank. Critics and proponents

disagree over the intent behind the structure, its route,

and its name. References to it include the "wall,

separation wall, security fence, Apartheid Wall,

separation barrier, annexation wall." Begun in 2002,

its construction is still in progress. For a map of the existing

structure and proposed route, please visit

www.btselem.org. Israel claims security needs necessitate

its construction. Israel has modified some of the routes

in response to a High Court of Justice ruling as well as

in response to international pressure. Palestinians point

out that the wall was built unilaterally, seizing lands

recognized as illegally occupied by Israel according to

international law. They also maintain that the wall

steals privately owned land, and chokes off some cities

almost completely. For a thorough report entitled, see

the Economist’s: "A safety measure or a land

grab?" October 9, 2003. A debate about its

appropriateness sprung up after the International Court

of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion declaring it

a breach of international law. For criticism of the ICJ's

opinion, visit:

http://www.aijac.org.au/updates/Jul-04/120704.html 12

For a map of the existing

structure and proposed route, please visit

www.btselem.org. Israel claims security needs necessitate

its construction. Israel has modified some of the routes

in response to a High Court of Justice ruling as well as

in response to international pressure. Palestinians point

out that the wall was built unilaterally, seizing lands

recognized as illegally occupied by Israel according to

international law. They also maintain that the wall

steals privately owned land, and chokes off some cities

almost completely. For a thorough report entitled, see

the Economist’s: "A safety measure or a land

grab?" October 9, 2003. A debate about its

appropriateness sprung up after the International Court

of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion declaring it

a breach of international law. For criticism of the ICJ's

opinion, visit:

http://www.aijac.org.au/updates/Jul-04/120704.html 12

http://www.democratic-edu.org/International/AboutUs/Activities.aspx. 13

Hadera An Israeli city 60 km North of Tel Aviv. Est. population 75,000. 14

Adam School Founded in 1992, the Jerusalem Waldorf Adam School focuses on the promotion of peace and understanding between Arabs and Jews through the involvement of children from both cultures in mutually beneficial activities. (source: http://www.rsfoundation.org/pages/proj_children.htm)

Attached to the Adam School in Jerusalem but teaching

music in the darkened rooms under threat of closure

Hasadna Conservatory is one of only three non-formal institutions teaching music in Jerusalem, together with the Rubin Conservatory and an additional conservatory in the haredi community.

But at this time, Hasadna is operating without electricity or heat and teachers are instructing by candelight. According to director Lena Nemerovsky, final closure may be unavoidable.

Hasadna was created some 33 years ago in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War by Amalia Reuel and Aliza Levin, who created a nonprofit organization to support music instruction for aspiring musicians. Since then, Hasadna has trained generations of young and gifted musicians in the city, many of whom have joined some of the most prestigious musical institutions in Israel and abroad.

The Conservatory is housed in the "Adam" school building on Rehov Emek Refaim. Sitting in the darkened music room, Nemerovsky says that she is trying to understand "what went wrong and how this highly regarded institution became nothing more a thorn in the municipality's side."

She relates, "Two weeks ago we came into the school as usual and found the electricity had been turned off. Surrounded by dozens of kids afraid of the dark and freezing without heating, I tried desperately to reach someone at the municipality. I tried all the phone numbers I could, all the officials related to education, culture - nobody cared to even answer me, let alone to do something."

Nemerovsky began teaching by candlelight and emergency lighting. "So imagine my surprise," she continues, "when just as we found this dramatic alternative to electricity a municipal supervisor popped in and ordered us to stop, since it's not safe to use candles. I was speechless - they didn't even care to answer my calls but already had someone ready to come and shut us down!?"

The space in the Adam School was allocated by the municipality. "In other cities," Nemerovsky contends, "the municipality gives an institution like Hasadna a building of its own and an annual subsidy. The municipality offered us the building, and that's the way it's worked for years."

But since the year 2000 schools in Jerusalem operate according to the "closed budget" system, and in order to survive, most schools rent out their facilities in the afternoon.

The municipality allocated Hasadna the sum of NIS 120,000 a year, to pay for the use of the rooms and the maintenance. But in 2005, the municipality slashed its budget as part of the rehabilitation program.

In January 2006, the municipality informed Hasadna that their allocation would be cut to NIS 60,000, retroactive to 2005. At the same time, the municipality demanded that Hasadna sign a formal commitment to pay the Adam School the sum of NIS 120,000, as they have in the past.

"How can I take on such a commitment?!" Nemerovsky complains. "I didn't sign and the municipality is refusing to give us even the NIS 60,000."

In turn, the Adam School shut down the electricity and has threatened to expel Hasadna.

Explains Ossi Rotem, a member of the parents' association of the Adam School, "We have nothing personal against Hasadna. The absurdity is that most of their students are our students. It's a situation of dire need - we need that money for the school, and the only way we can get it is by renting out the facility in the afternoon. If the Conservatory wants to use the building, they have to pay rent. Under the system that the municipality has imposed, we cannot function without that money."

Adds Alex Razumov, Vice Principal of the Adam School,

"That the parents of the Adam School would have to

pay for the Conservatory is out of the question. It's not

that I don't sympathize with their struggle... My son

studies music there and I am very satisfied. But... they

have a problem with the municipality, and they can't

throw it onto a third party, which, in this case, is

us."

Deputy Mayor Yigal Amedi, who holds the municipal portfolio for cultural affairs, says that he is trying to reach an arrangement.

Hasadna seems to be falling between the proverbial cracks. The education department contends that, since Hasadna is not a formal educational establishment, it did not meet its criteria and referred it to the culture department. But the culture department funds only performing institutions.

"We do not perform," says Nemerovsky. "We teach. We raise the next generation of performers. But that doesn't fit anyone's criteria."

So Amedi proposed to create a commission composed of representatives of the culture and education departments and of the committee responsible for the criteria for allocations to resolve the catch-22.

"But they have to sign the contract with the Adam School for the total sum," Amedi demands. "As for the remaining NIS 60,000, we'll try to divide it between the Education Ministry and some other sources. I'm still working it out."

While Nemerovsky acknowledges the help that Amedi is trying to offer, she still won't commit to the full sum without any guarantees. And so everyone loses out - the Adam School doesn't get its rent and Hasadna continues to teach in the dark and the cold.

The problem, says a high-ranking source in the municipality, who spoke on condition of anonymity, is the attitude of the municipality. "The municipality does not consider a music conservatory as important as a chewing-gum cleaning machine or some populist cultural event. The municipal culture department has been without a director for over two years and the department has shrunk from more than 200 employees to fewer than 100. If that is not a clear message for the priority orders of this mayor and his administration then I don't know what a message is," concludes the employee.

Attorneys at the legal department of the municipality point out that Nemerovsky already owes the Adam School NIS 178,000 for rent and maintenance. And municipal spokesman Gidi Schmerling told In Jerusalem that, "Hasadna is a nonprofit association, and as such, the organization and its board are responsible for its activities and administration."

Schmerling also notes that the three informal music institutions do not provide the only opportunity that Jerusalem schoolchildren have to learn music. One or two hours of music instruction are offered in every elementary school, funded by the Education Ministry. He adds that there are also special frameworks in many schools, such as choirs, musical ensembles, orchestras, and musical instruction, as well as enrichment programs, including instruction in the shepherds flute in second and third grades, funded by the ministry, the Jerusalem Education Authority, and the schools themselves, and after-school programs.

Nemerovsky remains unpersuaded, relating to the quality of the classical education and training that students receive at Hasadna.

"A few days ago," she recalls, "I went

to a concert by one of Israel's symphony orchestras. The

first violinist is not an Israeli, nor are two other

musicians. My institution is the only answer to this very

sad situation: within a short time, all our musicians

will be foreign workers. "Is this so trivial that

this municipality, the capital of Israel, cannot find NIS

60,000? I have 26 immigrant children from Ethiopia and 20

autistic kids. We have religious kids, 12 Arab kids, even

a kid from Beit Jalla. We give stipends to 75 percent of

our students. Isn't that important enough?"

Meanwhile, Nemerovsky has appealed to the administrative

courts, and District Judge David Cheshin has issued a

ruling freezing all decisions until a hearing scheduled

for this Tuesday, February 27.

MEANTIME HERE IS A PICTURE OF

aaCADEMICS IN eNGLAND, iRELAND AND aMERICA

| Don't

romanticise academia - it has a power structure

like company life By Professor Brian DePasquale Published: March 2 2006 02:00 | Last updated: March 2 2006 02:00 FROM LETTERS TO THE FINANCIAL TIMES Sir, While I found Lucy Kellaway's column concerning the difficult task of managing academics interesting, her analysis is skewed by her romanticising of the life of an academic ("Why academics make an unfit subject for management", February 27). It is common for most to elevate academics above the masses, forming ideals of academics as genius demigods who cannot be reined in by authority. This is far from the truth, especially in the sciences (contrary to Ms Kellaway's assertion) where cut-throat tactics are employed by scientists to emerge triumphant over rival scientists or labs. Within academia, even more romanticising occurs concerning those engaged in science (as displayed in Chris Wilkinson's article "Scientists in the playwright's laboratory" in the same edition). Due to the power structure of academia and the "tiny number" of professionals who may understand a specific field of research, brown-nosing may be more prevalent in academia than in any other institution; often, the opinion of one senior faculty member is all that is required to elevate a more junior academic to a position of increased institutional power. Her claim that there is no line of power would appear true on a superficial level, but for those of us observing these institutions from within, a clear line of authority is observed, one based on faculty rank, clout within one's field, frequency of article citation and so on. Furthermore, this subtle form of power struggle, contrary to her statements, forces academics to be "team players". In order to follow the rules of power within these institutions, lower-ranking persons will fold to those in power, forming a consensus around those with power. Although it may seem that for academics "criticism is a way of life", those without power will always back down to those with power, swallowing their criticisms for their own professional self-benefit. As for what happens when one does not bow down to power, speak to Norman Finkelstein or Francisco Gil-White. In short, while it seems attractive to romanticise academics, the power structure of a university research centre is surprisingly similar to that of a private corporation. Brian D. DePasquale, McGovern Institute for Brain Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, US Professors always

have the last word Sir, As a fervent reader of Lucy Kellaway's column and, more importantly, as the grand-nephew, grandson, son and brother of university professors, let me give wonderful Lucy some piece of much needed advice: Do what you want and write what you please, but never - repeat, never - say anything less than pleasant about university professors ("Why academics make an unfit subject for management", February 27). It is they who have the last word - or this, they think, is their right since birth. They will never give it up. God save Lucy from the fury of the

iconoclast's iconoclasts. Ms Kellaway, I fear, is the one in the ivory

tower Really? I walked past the "recent publications" noticeboard of the economics department at the University of Strathclyde today and counted that about 80 per cent of publications were multi-authored (or team produced). Go into the sciences in the university (indeed most universities) and the multi-author team count increases. Contrast that with Ms Kellaway's opinion on a subject she clearly knows little to nothing about, and which could have been solo-authored from a cottage in the Cotswolds or a farmhouse in France, and ask the reasonable question - who is writing from an ivory tower divorced from reality? Neil Kay, Innellan, Argyll PA23 7SP, UK (Emeritus Professor, Department of Economics, University of Strathclyde) |

| AND HERE A RABBI

FULMINATING AGAINST A PROPOSED SCHOOL FOR ARABS

AND JEWS IN ISRAEL: ZNet Commentary An Experiment in Anti-Semitism vs. Anti-Arab Racism March 03, 2006 By Chris Spannos Imagine if an Arab spiritual leader referred to Jews as "foul", a "disease" or as a "devil". What if he called them "asses" and asked "why did God not create them walking on their fours?" In reply to his own rhetorical question, the imaginary Arab spiritual leader then coolly replies, "The answer is that they need to build and wash." You would be right to be angry and disgusted by such vile racism. And you would be right to wonder what institutional and cultural influences help create, perpetuate and sustain such anti-Semitic garbage. But would you feel and think the same way if it was a Jewish spiritual leader targeting Arabs with this hateful, racist nonsense? We certainly hear, see and read both genuine and exaggerated claims of anti-Semitism almost daily in radio, T.V. and newspaper reports. But we don't see balanced attention given to anti-Arab racism. If we had the resources to conduct a methodical and systematic study documenting the discrepancy between media coverage of anti-Semitism and media coverage of anti-Arab racism I'm willing to bet that we'd find conclusive evidence of a profound neglect. And the source of this neglect can be found in the hesitation and fear of criticizing the state of Israel's policies and illegal occupation; the fear of being called an anti-Semite. Since all Jews do not identify with the state of Israel, or Zionism, despite Zionism's claim to act on behalf of all Jews, the accusation of anti-Semitism is of course nonsense. I opened this commentary with "Imagine if an Arab spiritual leader...". There is in fact no real person as such. However, all the insults and vitriol spewed in this hypothetical anti-Semitism are the real words of a Jewish spiritual leader, Rabbi David Bazri, directed at Palestinians. His racist attack comes in the wake of a very sane, reasonable and necessary proposal for the establishment of a mixed Arab-Jewish school in Pat, Jerusalem. Now it is true that anti-Semitism exists in the Arab World, just as anti-Arab racism exits among Jews. But not all Arabs are anti-Semites, just as not all Jews are racist. But it is not true, as the well documented daily humiliations of occupied Palestinian lives testify, that these forms of racism are given equal attention and consequently have equal outcomes. If the particular hypothetical anti-Semitism used here were a real incident, you can be sure it would receive wide spread media and political attention, used to justify Israel's illegal occupation - more rational to reign collective punishment down upon the Palestinians. But the opposite is true; a particularly nasty anti-Arab racism was expressed. Will we see newspaper, T.V. or radio reports covering these extremely hysteric remarks? Why not? Do we even care? Can we even begin to ask what institutional and cultural influences help create, perpetuate and sustain such anti-Arab garbage? Would equal attention and examination of these issues illuminate the failings of a flawed ideology - Zionism, or the brutalities of Israel's occupation? In contrast to the hypothetical anti-Semitism above, the response to real anti-Arab racism directed at Palestinians from a Jewish spiritual leader is a vacuum of silence from our political leaders and dominant media institutions. Walla!News (Haaretz) reported on Jan. 10, in a news item appearing only in Hebrew (see here for an unofficial English translation), that "Today the school is running in a temporary building and is looking for a permanentresidence in the Pat neighborhood of Jerusalem. The municipality assigned a territory for the school but because of repeating appeals to court the process isdelayed. Today [Jan 10.] the matter is scheduled for a debate in the High Court." A Rabbi named Yehuda Der'i also participated in the conference against the school and said that "this is a thing that the Jewish mind, logic and soul cannot tolerate. We have to go from house to house and raise supporters in the neighborhood to prevent this horrid punishment." More vacuous comments, and the news item quoted here is actually worse than I've let on... Here are Rabbi David Bazri's words, in full, which I quoted above for the hypothetical anti-Semitism, "The establishment of such a school is a foul, disgraceful deed. You can't mix pure and foul. They are a disease, a disaster, a devil. The Arabs are asses, and the question must be asked, why did God not create them walking on their fours? The answer is that they need to build and wash. They have no place in our school". This gross racist assault against a proposed school provides one window peering into the daily humiliations that Palestinians suffer in Israel. It is the foundation for the belief that there are "pure" and "foul" races, ethnic groups and cultures; and in the particular case of Israel, that there can be a "pure" "Jewish State". It enables the existence of second class citizenship for Palestinians in Israel, identification cards for Palestinians, checkpoints for Palestinians, systematic house demolitions for Palestinians, extra judicial executions and assassinations for Palestinians, an Apartheid Wall for Palestinians, a brutal military occupation which has practiced ethnic cleansing and denied Palestinians their Right of Return. It is a backward and insipid thinking that belongs to the Stone Age. Sadly, anti-Arab racism is not confined to Israel alone. The US and Canada are both engaged in the illegal detention, deportation and torture of Arabs. As Noam Chomsky has noted "Anti-Arab racism in the US has long been extreme, the last "legitimate" form of racism in that one doesn't even have to pretend to conceal it. That's long before 9-11, and a deep problem in the society, which can't be ignored, any more than other forms of racism can." But that will have to be the topic of another commentary. Chris Spannos is an anti-war activist, anti-capitalist, ZNet volunteer and member of the Vancouver Participatory Economics Collective. His email address is: spannos at gmail dot com He blogs for ZNet at http://blog.zmag.org |