JULY 2007

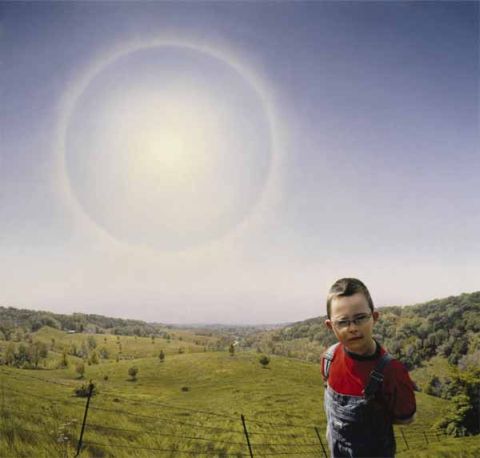

The fragile planet:

Thoughts of a green prophet

The fragile planet:

Thoughts of a green prophet

Back in the 1970s, Barry Commoner was one of the first environmentalists to warn that the earth had limits - and human society was on course to exceed them. Now, as he turns 90, his message is more relevant than ever. By Michael McCarthy reports

Published: 20 June 2007

Here's a green landmark: one of the modern environment movement's early prophets, and most original thinkers, has turned 90. Barry Commoner, distinguished cellular biologist, leading eco-campaigner and one-time US presidential candidate, was among the formulators of the green movement's essential message, which we could characterise like this: there is only so much that the earth can take.

He is still sending out his message loud and clear. Remarkably active both in body and mind, still regularly commuting to the Centre for the Biology of Natural Systems at the City University of New York (he stepped down as director in 2000 at the age of 83), he gave an interview to The New York Times yesterday in which he surveyed the world of the 21st century with a mixture of hope and pessimism.

His is a key viewpoint. When the history of environmentalism is definitively written, one theme above all others, which Professor Commoner helped to shape, will stand out: the realisation, so long in coming for humankind, that the earth is finite.

For millennia, there had been the assumption that the planet was limitless, and we could plunder its natural resources, from fish to forests, without any fear of them running out; we could dump waste to our heart's content on the land and the sea, and it would be absorbed without harm; we could dream up an infinity of new inventions and be heedless of their side-effects.

But Commoner was one of a group of visionaries who in the 1960s and 1970s saw that this assumption was dangerously wrong.

Three key events mark out modern environmentalism' s beginnings. The first was the publication in 1962 of Silent Spring, the devastating indictment of the effects of large-scale spraying of agricultural pesticide on American wildlife by Rachel Carson (the centenary of whose birth was celebrated last month). That woke people up to the fact that we were visibly harming the natural world on a large scale. The second was the taking of the first pictures of the earth from a distance, captured by the astronauts of the US Apollo 8 spacecraft in December 1968, returning from their trip around the moon. For the first time ever humanity saw its only home, an exquisite blue sphere hanging in the blackness of space, which more than anything seemed small and immensely fragile.

And the third was the 1972 publication, by a small group of thinkers calling themselves the Club of Rome, of The Limits to Growth, an analysis of the world's natural resource supply, which claimed that with rapidly increasing rates of consumption, key commodities, from oil to coal, would run out within decades.

These predictions were soon proved wrong, but what the book had done was to stamp indelibly in the human consciousness the idea that even though it might be a long way off, in the end there was a limit to what the Earth could provide.

There was a fourth event also, influential at the time, but now largely ignored: the 1968 publication of The Population Bomb, by the biologist Paul Ehrlich, who claimed that rapidly rising populations would lead to the death by mass starvation of tens of millions of people in the 1970s and 1980s. Ehrlich's predictions, like those of the Club of Rome, were soon found to be wide of the mark, but his thesis similarly established a general idea: that the pressure of human numbers would start to affect the planet seriously.

Into this awakening consciousness of the earth's vulnerability, Commoner added two further insights: the specific dangers of technology, and the fact that when dealing with the natural environment, there is no free lunch.

As a professor at Washington University in St Louis, Missouri, he had come to environmentalism through opposition to nuclear weapons testing, being particularly concerned with the effects on the environment of radioactive fall-out from atmospheric tests in the continental US (which before the nuclear test-ban treaty of 1963 were regular occurrences).

Commoner set up a committee to obtain details about the results of the tests, many of which had been kept secret, and established that they could lead to a build-up of radioactivity in humans. This itself helped bring about the test-ban treaty, But his concerns broadened to other malign effects of technologies such as industrial pollution, and he set out his stall in a celebrated book, Science and Survival, published in 1967, which sounded an alarm about the deployment of technology before the side-effects had been properly thought through.

It turned him into a prophet - he made the cover of Time magazine in 1970 when that really meant something - and then he went further with what is regarded as his classic work, The Closing Circle, published in 1971. Here he argued that there were three possible causes of environmental degradation: population growth, increasing affluence, and modern technology. The last was the key factor, he said (sparking a public debate with Paul Ehrlich).

More significantly still, he pointed out memorably the reason why phenomena such as large-scale industrial production caused such harm: because the waste products could not be made to disappear. When you threw something away, he said, there was really no "away" to throw it to; it had to go somewhere in the biosphere, the thin layer of life enveloping the Earth.

This insight led him to formulate his Four Laws of Ecology, which became his most memorable statement. They are:

1. Everything is Connected to Everything Else. There is only one biosphere for all living things and what affects one, affects all.

2. Everything Must Go Somewhere . The idea that waste products can be made to disappear is an illusion.

3. Nature Knows Best. People have tried to fashion technology to improve upon nature, but such change in a natural system is "likely to be detrimental to that system," Commoner says.

4. There Is No Such Thing as a Free Lunch. In the natural world, for every gain there is a cost, and all debts are eventually paid; both sides of the equation must balance.

From here Commoner went on to understand that products needed to be seen over the whole of their life-cycle; he was one of the very first advocates of recycling. His thinking had a considerable effect on the first generation of British environmentalists, such as the energy guru Walt Patterson, the green campaigner Tom Burke and Jonathon Porritt, now chairman of the Government's green watchdog body, the Sustainable Development Commission.

"The Closing Circle was an amazing book," Jonathon Porritt said yesterday. "Barry Commoner was one of the first people to understand how materials flow through nature and through society, and to say that 'to chuck away' was a really dangerous concept, because there was no 'away' - it all had to be dealt with within the whole of nature. He was a really early holistic thinker."

Professor Commoner went on to have a go at becoming President Commoner - he stood for the Citizens' Party in the 1980 US presidential election (in which the Democrat incumbent Jimmy Carter was beaten by the Republican Ronald Reagan.) He polled 233,052 votes (0.27 per cent of the total) and the highlight of the campaign, he told The New York Times yesterday, was in Albuquerque, New Mexico, when a local reporter asked him: "Dr Commoner, are you a serious candidate or are you just running on the issues?"

His interviewer reminded him that in 1970 he had said: "We have the time - perhaps a generation - in which to save the environment from the final effects of the violence we have done to it", and asked him for his view today.

He replied: "We've really failed to do more than a few specific things. We don't use DDT on the farm any more. We don't use lead in gasoline anymore. Environmental pollution is an incurable disease. It can only be prevented. And prevention can only take place at the point of production. If you insist on using DDT, the only thing you can do is stop. The rest has really been sort of forgotten about. Except that now, global warming has sort of consolidated the independent environmental hazards that many of us had been working on all of these years." He went on: If you ask what you are going to do about global warming, the only rational answer is to change the way in which we do transportation, energy production, agriculture and a good deal of manufacturing. The problem originates in human activity in the form of the production of goods.

"The Chinese like to say, 'Crisis means change'. It means you can get things done. Unfortunately, I think that most of the 'greening' that we see so much of now has failed to look back on arguments such as my own - that action has to be taken on what's produced and how it's produced. That's unfortunate, but I'm an eternal optimist, and I think eventually people will come around."

Asked what he thought of the debate in the United States over the extent to which humans are primarily responsible for global warming, he said: "No one in his right mind would deny that we're getting warmer. The question is, is this due to things that people have chosen? And I think the answer is that all of the things we have chosen to do include the release of materials like carbon dioxide, which affect the retention of heat by the planet.

"You could argue that maybe this is a high point in a heating/cooling cycle. Well, we're adding to the high point. There's no question about it. So it seems to me the argument that there are natural ways in which the temperature fluctuates is a spurious one. If we accept that we're in a cycle, it's idiocy to increase the high point."

Asked if he had ever been tempted to run for President again, Commoner said: "Often. Every time Bush does anything, I feel I should have won."

Commoner's Four Ecology Laws

1. Everything is Connected to Everything Else

2. Everything Must Go Somewhere

3. Nature Knows Best

4.

There Is No Such Thing as a Free Lunch Emailing The fragile planet Thoughts of

a green prophet - Independent Online Edition Climate

Change.htm