THE HANDSTAND

june 2005

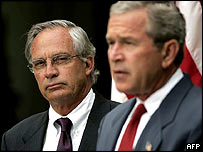

Proof Bush Fixed The Facts

Ray McGovern©May 04, 2005

Ray McGovern served 27 years as a CIA analyst and is now on the Steering Group of Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity. He works for Tell the Word, the publishing arm of the ecumenical Church of the Saviour.

"Intelligence and facts are being fixed around the policy."

Never in our

wildest dreams did we think we would see those

words in black and white - and beneath a secret stamp, no

less. For three years now, we in  Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity

(VIPS) have been saying that the CIA and its British

counterpart, MI-6, were ordered by their countries'

leaders to "fix facts" to "justify"

an unprovoked war on Iraq. More often than not, we

have been greeted with stares of incredulity.

Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity

(VIPS) have been saying that the CIA and its British

counterpart, MI-6, were ordered by their countries'

leaders to "fix facts" to "justify"

an unprovoked war on Iraq. More often than not, we

have been greeted with stares of incredulity.

It has been a hard

learning—that folks tend to believe what they want

to  believe. As long as our

evidence, however abundant and persuasive, remained

circumstantial, it could not compel belief. It

simply is much easier on the psyche to assent to the

White House spin machine blaming the Iraq fiasco on bad

intelligence than to entertain the notion that we were

sold a bill of goods.

believe. As long as our

evidence, however abundant and persuasive, remained

circumstantial, it could not compel belief. It

simply is much easier on the psyche to assent to the

White House spin machine blaming the Iraq fiasco on bad

intelligence than to entertain the notion that we were

sold a bill of goods.

Well, you can forget circumstantial. Thanks to an unauthorized disclosure by a courageous whistleblower, the evidence now leaps from official documents—this time authentic, not forged. Whether prompted by the open appeal of the international Truth-Telling Coalition or not, some brave soul has made the most explosive "patriotic leak" of the war by giving London's Sunday Times the official minutes of a briefing by Richard Dearlove, then head of Britain's CIA equivalent, MI-6. Fresh back in London from consultations in Washington, Dearlove briefed Prime Minister Blair and his top national security officials on July 23, 2002, on the Bush administration's plans to make war on Iraq.

Blair does not dispute the authenticity of the

document, which immortalizes a discussion that is

chillingly amoral. Apparently no one felt free to

ask the obvious questions. Or, worse still, the

obvious questions did not occur.

Blair does not dispute the authenticity of the

document, which immortalizes a discussion that is

chillingly amoral. Apparently no one felt free to

ask the obvious questions. Or, worse still, the

obvious questions did not occur.

Juggernaut Before The Horse

In emotionless English,

Dearlove tells Blair and the others that President Bush  has decided to remove Saddam Hussein by

launching a war that is to be "justified by the

conjunction of terrorism and weapons of mass

destruction." Period. What about the

intelligence? Dearlove adds matter-of-factly,

"The intelligence and facts are being fixed around

the policy."

has decided to remove Saddam Hussein by

launching a war that is to be "justified by the

conjunction of terrorism and weapons of mass

destruction." Period. What about the

intelligence? Dearlove adds matter-of-factly,

"The intelligence and facts are being fixed around

the policy."

At this point, Foreign Secretary Jack Straw confirms that Bush has decided on war, but notes that stitching together justification would be a challenge, since "the case was thin." Straw noted that Saddam was not threatening his neighbors and his WMD capability was less than that of Libya, North Korea or Iran.

In the following months, "the case" would be buttressed by a well-honed U.S.-U.K. intelligence-turned-propaganda-machine. The argument would be made "solid" enough to win endorsement from Congress and Parliament by conjuring up:

- Aluminum artillery

tubes misdiagnosed as nuclear related;

- Forgeries alleging Iraqi attempts to obtain uranium in Africa;

- Tall tales from a drunken defector about mobile biological weapons laboratories;

- Bogus warnings that Iraqi forces could fire WMD-tipped missiles within 45 minutes of an order to do so;

- Dodgy dossiers fabricated in London; and

- A U.S. National Intelligence Estimate thrown in for good measure.

All this, as Dearlove notes dryly, despite the fact that "there was little discussion in Washington of the aftermath after military action." Another nugget from Dearlove's briefing is his bloodless comment that one of the U.S. military options under discussion involved "a continuous air campaign, initiated by an Iraqi casus belli"—the clear implication being that planners of the air campaign would also see to it that an appropriate casus belli was orchestrated.

The discussion at 10 Downing St. on July 23,

2002 calls to mind the first meeting of George W. Bush's

National Security Council (NSC) on Jan. 30, 2001, at

which the president made it clear that toppling Saddam

Hussein sat atop his to-do list, according to

then-Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neil, who was there.

O'Neil was taken aback that there was no discussion of

why it was necessary to "take out"

Saddam. Rather, after CIA Director George Tenet

showed a grainy photo of a building in Iraq that he said

might be involved in producing chemical or biological

agents, the discussion proceeded immediately to which

Iraqi targets might be best to bomb. Again, neither

O'Neil nor the other participants asked the obvious

questions. Another NSC meeting two days later

included planning for dividing up Iraq's oil wealth.

The discussion at 10 Downing St. on July 23,

2002 calls to mind the first meeting of George W. Bush's

National Security Council (NSC) on Jan. 30, 2001, at

which the president made it clear that toppling Saddam

Hussein sat atop his to-do list, according to

then-Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neil, who was there.

O'Neil was taken aback that there was no discussion of

why it was necessary to "take out"

Saddam. Rather, after CIA Director George Tenet

showed a grainy photo of a building in Iraq that he said

might be involved in producing chemical or biological

agents, the discussion proceeded immediately to which

Iraqi targets might be best to bomb. Again, neither

O'Neil nor the other participants asked the obvious

questions. Another NSC meeting two days later

included planning for dividing up Iraq's oil wealth.

Obedience School

As for the briefing of

Blair, the minutes provide further grist for those who  describe the U.K. prime minister as Bush's

"poodle." The tone of the conversation

bespeaks a foregone conclusion that Blair will wag his

tail cheerfully and obey the learned commands. At one

point he ventures the thought that, "If the

political context were right, people would support regime

change." This, after Attorney General Peter

Goldsmith has already warned that the desire for regime

change "was not a legal base for military

action,"—a point Goldsmith made again just 12

days before the attack on Iraq until he was persuaded by

a phalanx of Bush administration lawyers to change his

mind 10 days later.

describe the U.K. prime minister as Bush's

"poodle." The tone of the conversation

bespeaks a foregone conclusion that Blair will wag his

tail cheerfully and obey the learned commands. At one

point he ventures the thought that, "If the

political context were right, people would support regime

change." This, after Attorney General Peter

Goldsmith has already warned that the desire for regime

change "was not a legal base for military

action,"—a point Goldsmith made again just 12

days before the attack on Iraq until he was persuaded by

a phalanx of Bush administration lawyers to change his

mind 10 days later.

The meeting concludes with a directive to "work on the assumption that the UK would take part in any military action."

I cannot quite fathom

why I find the account of this meeting so jarring.

Surely it is what one might expect, given all else we

know. Yet seeing it in bloodless black and white

somehow gives it more impact. And the implications

are no less jarring.

One of Dearlove's primary interlocutors in Washington was his American counterpart, CIA director George Tenet. (And there is no closer relationship between two intelligence services than the privileged one between the CIA and MI-6.) Tenet, of course, knew at least as much as Dearlove, but nonetheless played the role of accomplice in serving up to Bush the kind of "slam-dunk intelligence" that he knew would be welcome. If there is one unpardonable sin in intelligence work, it is that kind of politicization. But Tenet decided to be a "team player" and set the tone.

Politicization: Big Time

Actually, politicization is far too mild a word for what happened. The intelligence was not simply mistaken; it was manufactured, with the president of the United States awarding foreman George Tenet the Medal of Freedom for his role in helping supervise the deceit. The British documents make clear that this was not a mere case of "leaning forward" in analyzing the intelligence, but rather mass deception—an order of magnitude more serious. No other conclusion is now possible.

Small wonder, then, to learn from CIA insiders like former case officer Lindsay Moran that Tenet's malleable managers told their minions, "Let's face it. The president wants us to go to war, and our job is to give him a reason to do it."

Small wonder that, when

the only U.S. analyst who met with the alcoholic Iraqi  defector appropriately codenamed

"Curveball" raised strong doubt about

Curveball's reliability before then-Secretary of State

Colin Powell used the fabrication about "mobile

biological weapons trailers" before the United

Nations, the analyst got this e-mail reply from his CIA

supervisor:

defector appropriately codenamed

"Curveball" raised strong doubt about

Curveball's reliability before then-Secretary of State

Colin Powell used the fabrication about "mobile

biological weapons trailers" before the United

Nations, the analyst got this e-mail reply from his CIA

supervisor:

"Let's keep in mind the fact that this war's going to happen regardless of what Curveball said or didn't say, and the powers that be probably aren't terribly interested in whether Curveball knows what he's talking about."

When Tenet's successor,

Porter Goss, took over as director late last year, he  immediately wrote a memo to all employees

explaining the "rules of the road"—first

and foremost, "We support the administration and its

policies." So much for objective intelligence

insulated from policy pressure.

immediately wrote a memo to all employees

explaining the "rules of the road"—first

and foremost, "We support the administration and its

policies." So much for objective intelligence

insulated from policy pressure.

Tenet and Goss, creatures of the intensely politicized environment of Congress, brought with them a radically new ethos—one much more akin to that of Blair's courtiers than to that of earlier CIA directors who had the courage to speak truth to power.

Seldom does one have documentary evidence that intelligence chiefs chose to cooperate in both fabricating and "sexing up" (as the British press puts it) intelligence to justify a prior decision for war. There is no word to describe the reaction of honest intelligence professionals to the corruption of our profession on a matter of such consequence. "Outrage" does not come close.

Hope In Unauthorized Disclosures

Those of us who care about unprovoked wars owe the patriot who gave this latest British government document to The Sunday Times a debt of gratitude. Unauthorized disclosures are gathering steam. They need to increase quickly on this side of the Atlantic as well—the more so, inasmuch as Congress-controlled by the president's party-cannot be counted on to discharge its constitutional prerogative for oversight.

In its formal appeal of Sept. 9, 2004 to current U.S. government officials, the Truth-Telling Coalition said this:

We know how misplaced loyalty to bosses, agencies, and

careers can obscure the higher allegiance all government officials owe the Constitution, the sovereign public, and the young men and women put in harm's way. We urge you to act on those higher loyalties...Truth-telling is a patriotic and effective way to serve the nation. The time for speaking out is now.

If persons with access

to wrongly concealed facts and analyses bring them to

light, the chances become less that a president could

launch another unprovoked

war—against, say, Iran.

Published on 9 May 2005 by New Statesman. Archived on 6

May 2005.

'The people and the political class are at one: neither wants to face the future'

by John Gray

Election: the future - the big picture

The election has resolved nothing. Britain continues to

drift, its meandering course guided by the conventional

wisdom of a generation ago. Crucial questions of national

policy were fudged or deferred, so that when the

government does find itself forced to take decisions on

them, it will do so without the benefit of forethought or

serious public debate. One reason for the palpable public

boredom that accompanied most of the campaign was that it

was largely fought around pseudo-issues. All the parties

studiously avoided talking about the realities that will

shape our lives over the coming years.

Within a decade or so, maybe sooner, a combination of

accelerating climate change and the peaking of global oil

supplies will put great strain on our present

energy-intensive way of life, but the political class has

decided to postpone thinking about the environmental

crisis. The war in Iraq grinds on with Britain a hapless

accomplice in the Bush administration's bungling and

barbarism, and yet none of the parties asked whether the

so-called special relationship with the US continues to

serve the British national interest. Despite recent signs

of slowdown, the domestic economy goes on producing jobs

and rising incomes for the majority, but this prosperity

is heavily dependent on unsustainable household

borrowing. Sooner or later the debt binge will be

followed by a hangover - an uncomfortable prospect that

no one cares to think about.

Indeed, reality was hardly allowed to obtrude on the

campaign at all. Debate was locked into the tired slogans

of the 1990s, if not the 1980s. More than a quarter of a

century after she came to power, British public discourse

continues to be shaped by Margaret Thatcher, and her

message of free markets and consumer choice is still the

only story in British politics. In different ways all the

major parties lay claim to her inheritance, and none has

dared ask if the simple nostrums she propagated a

generation ago contain answers to the problems we face

today. The juggernaut of marketisation rolls on,

flattening everything in its way. Oxford University looks

poised to follow the BBC in reshaping itself on a dated

model of the business corporation. The few remaining

self-governing institutions seem bent on

self-destruction.

A peculiar kind of market corporatism is entrenched

throughout British life, and the autonomous institutions

of which we could once be justly proud are now barely a

memory. More crudely and mechanically than in Thatcher's

time, public policy is ruled by the belief that if market

mechanisms are the most efficient way of organising the

economy, then they must be injected into every last

corner of social life.

The idea that markets work best when they are

complemented by institutions run on non-market principles

used to be part of the country's tacit constitution, but

it is evidently too subtle for the British today. At the

same time, the discrepancy between the rhetoric of market

choice and everyday experience becomes ever greater. We

are all familiar with the chaos of the railways and the

postal service, the deformation of education by incessant

monitoring, and the absurdities that go with targeting in

healthcare. British public institutions are now deeply

dysfunctional, and yet all the major parties remain

wedded to the neo-Thatcherite programme that has brought

about this state of affairs.

As a by-product of this neo-Thatcherite consensus,

British politics is dominated by what Freud called

"the narcissism of minor differences". The gap

between Labour and the Tories on acceptable levels of

taxation and public spending is insignificant, and even

on the toxic issues of Europe and immigration their

positions are not as far apart as they pretend. Among the

major parties, only the Liberal Democrats have maintained

a principled stance on the Iraq war, and Charles Kennedy

deserves great credit for stating that he favours an

early withdrawal of British forces. On this ground alone,

the Liberal Democrats deserved the vote of anyone who

cared about honesty or simple decency in politics. Yet

even they did not make clear the revolutionary shift in

Britain's international position that withdrawing support

for the US in Iraq implies. Nor did they spell out what

an alternative UK foreign and defence policy would look

like.

Again, in domestic policy, the Liberal Democrats are not

as different from the other parties as they like to

think. They, too, bow before the altar of

neo-Thatcherism, and what they are offering is only a

more upfront version of the mix of market forces and

income redistribution that Labour has implemented by

stealth.

Despite their efforts to manufacture divisions, all the

main parties offered a continuation of the status quo -

at a time when it is fast becoming unsustainable. This is

nowhere clearer than in environmental policy. All the

parties accepted the fact of climate change, and even

Michael Howard said the Bush administration was wrong to

deny the reality of humanly caused global warming. Yet no

party grasped the scale and urgency of the environmental

challenge. Mounting scientific evidence suggests climate

change is happening faster than anticipated, and a large

shift in the conditions under which we live is

inescapable. This evidence does not come mainly from

computer models, which some have dismissed as unreliable.

It is based on observation of physical processes that are

already under way, such as the melting of polar glaciers.

Whatever so-called sceptical environmentalists may

pretend, there is no serious scientific doubt about

accelerating climate change.

At the same time that global warming is speeding up and

becoming irreversible, "peak oil" - the point

at which world oil production reaches a peak and begins

to decline - may not be far away. Matthew Simmons, a

veteran oil expert who has advised the Bush

administration, even suggests in a forthcoming book -

Twilight in the Desert: the coming Saudi oil shock and

the world economy - that it has happened already in Saudi

Arabia, the country that is supposed to have the largest

reserves. If this is so, it poses a momentous challenge.

The industrialised world continues to be critically

dependent on oil, and renewable energy is nowhere near

filling the gap created by depleting fossil fuels.

Windfarms and solar power cannot maintain a world

population of six billion humans, nor support the sixty

million who live in the UK - let alone the higher

populations that are predicted. Before the election, the

Blair government was edging towards favouring nuclear

power - an option that, along with James Lovelock, I have

supported on environmental grounds for many years. But

there has been nothing resembling a national debate on

the subject, and all the parties - including the Greens -

remain in denial about the magnitude of the challenges

that lie ahead.

The denial of awkward facts is pervasive in British life,

and is shown in the failure to address rising levels of

debt. One of the paradoxes of Labour's embrace of

neo-Thatcherite orthodoxy on the virtues of old-fashioned

public finance is that it has gone hand in hand with the

encouragement of a post-modern culture of reckless

private borrowing. A considerable part of the general

prosperity of the Blair era has been fuelled by

credit-card debt and home-equity release, and a

"live today, pay tomorrow" mentality has become

deeply ingrained. For many people - including students

paying their way through university - debt has become a

necessity, but for many others it has become the means

whereby a standard of living that cannot be justified in

terms of earnings is kept going on the never-never.

This carpe diem philosophy has been reinforced by the

collapse of pensions. Old-style final-salary schemes are

dying out in the private sector, and - though the

government fell silent on its plans to scale them back in

the run-up to the election - they are under attack in the

public sector as well. In these circumstances, planning

for the future is a profitless exercise. Many people have

decided simply not to bother about saving; they go on

spending money they do not have, in the belief that

ever-rising house prices or a resumption of inflation

will bail them out of debts they cannot repay. For a

large part of the population, avoiding thinking about the

future is an integral part of their present quality of

life.

J K Galbraith's vision of private affluence and public

squalor is nowhere more fully realised than in Britain

today, and a good case can be made that the debt-fuelled

private consumption boom of the past eight years is an

integral part of the political economy of new Labour. So

long as personal spending power is high, the decaying

social infrastructure can be forgotten and the squalor of

public services shut out from conscious awareness.

Britain's voters have not given up on government and are

far from accepting the US model in which the state

retreats from social provision. At the same time, they

are unwilling to accept European levels of personal

taxation. New Labour has found a way out of this

conundrum by encouraging personal borrowing. Voters do

not feel the pain of rising taxes so much when their

living standards are buffered by debt, and the decision

to adopt an American or a European model can be put off.

Despite all the talk about hard choices, this is one -

one of many - that has been postponed.

Not for ever, though. At some point the bills will have

to be paid, and it may be sooner rather than later. Under

the impact of the ruinous cost of the Iraq war, the US

federal deficit is spiralling, and it is hard to see how

it can be brought under control. The Bush administration

would dearly love to bring back the troops, but it lacks

an exit strategy. To pull out of Iraq in the near future

would be to suffer a huge strategic defeat.

Just as bad, US withdrawal would leave Iraqi oil in limbo

- and it is here that the analogy with the war in Vietnam

breaks down. Despite the terrible suffering of those

involved, the Vietnam war was peripheral in its impact on

the rest of the world. During the long years the conflict

dragged on it became horribly normal and, when the US

finally pulled out, there was nothing like the feared

domino effect in the region. In contrast, the US in Iraq

can hardly afford to slog on with the war, but nor can it

bring it to an end. This is an impasse that cannot last,

and there is a risk it will be resolved by events - such

as serious unrest in Saudi Arabia. That could shake the

global economy to its foundations, triggering a collapse

of the dollar and stagflation in America. The ability of

the United States to continue with a ruinous war would be

compromised. And Britain's feckless prosperity would come

to a sudden end.

Whatever happens in the coming years, we can be sure

Britain will be gloriously unprepared. It is fashionable

to bemoan public estrangement from politics, but the

election campaign showed that in one respect at least,

the people and the political class are at one. Neither is

ready to question the status quo and think how to face

the future. As a result, crucial issues about Britain's

future are likely to be determined by events that voters

and politicians prefer not to think about.

John Gray's most recent book is Heresies:

against progress and other illusions,

published by Granta.

This article first appeared in the New Statesman.

For the latest in current and cultural affairs subscribe

to the New Statesman print edition.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Editorial Notes ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

According to the

RSA:

John Gray is Professor of European Thought at the London School of Economics.

Prior to his LSE appointment Gray was Professor of Politics at Oxford University and a fellow of Jesus College, Oxford. Gray has been an influential conservative thinker, working in the UK with the Institute of Economic Affairs and in the US with the Cato Institute, the Institute for Humane Studies, the Liberty Fund and the Social Philosophy and Policy Center. He was a key scholar — and ardent defender — of the work of Friedrich Hayek, in 1984 publishing the seminal Hayek on liberty.

During the 1990s, Gray revised his views to question free trade, the laissez-faire market system and the Enlightenment project more generally. He is now better known for his criticism of the excesses of neoliberal ideology, and has published several books on the subject...