THE HANDSTAND

june 2005

Joe Ambrose

Like the dope-fiend, who cannot move from place to place without taking with him a plentiful supply of his deadly balm I never venture far without a sufficiency of reading matter. Somerset Maugham

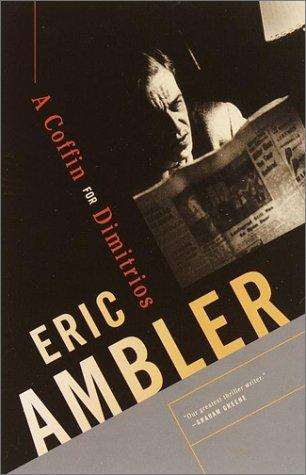

I became interested in Eric Ambler when some

English paperback house did a reissue of his best known

books, The Mask of Dimitrios, and Judgment of Deltchev.

I’m into those old Sydney Greenstreet/John

Houston/Orson Welles/Mittel Europe noir thrillers, and

Ambler contributed more than his fair share to that whole

niche of literary culture. Ambler is one of those

scarce-enough great writers who declined with age. There

must be a lesson for all of us in this.

I read Judgment in Deltchez one night in Fes

after watching Gladiator in French in one of about ten

perfectly preserved French Art Deco cinemas in Fes’s

Nouvelle Ville. That was a year ago. Now I’ve been

reading the furtive sweaty fiction of Eric Ambler on

three continents.

Ambler’s work divides into two distinct

phases and periods; the stuff he wrote before he retired

and what he did after he came back.

In the thirties he wrote Deltchev, Dimitrios,

and other Hitchcock/Graham  Greene type visions of European life under

threat, full of men without passports crushed by

dictatorships and liberal corruption, sinister Turkish

police chiefs who knew everything about fine wines and

the refined arts of physical torture. The narrators, like

the young Ambler, were often chaps from England with a

grounding in engineering, electricity, or some other new

world of science. This was smooth hip material, very

zeitgeist, very politically aware, very astute. No wonder

the noir directors ate it up and made Ambler a bankable

Hollywood name.

Greene type visions of European life under

threat, full of men without passports crushed by

dictatorships and liberal corruption, sinister Turkish

police chiefs who knew everything about fine wines and

the refined arts of physical torture. The narrators, like

the young Ambler, were often chaps from England with a

grounding in engineering, electricity, or some other new

world of science. This was smooth hip material, very

zeitgeist, very politically aware, very astute. No wonder

the noir directors ate it up and made Ambler a bankable

Hollywood name.

Then, just like it happened to everyone else,

World War II happened to Eric Ambler. This writer on

twisted loyalties, state police, nascent corporate life,

and cynicism in high office found himself playing an

active role in his nation’s intelligence

skullduggery. After the War, ironically, he didn’t

reinvest his fiction with the vast range of material he

undoubtedly came across in intelligence. Instead he

disappeared off into the glitzy world of moviemaking

where he no doubt became even richer than he already was.

Then there was a fiction comeback when Eric grew

older, when his cool barometer and his shit detector were

no longer working properly. By the early sixties he was

banging out a thriller a year. They sold and sold and

sold, often converted into lousy movies or TV

serializations, occasionally giving rise to the likes of

Topaki. Anyone who ever watched TV on a Sunday afternoon

has seen Topaki.

There was a seedy side to Phase Two Ambler. The

early books dealt with the dilemmas of young men who were

fit, impoverished, or alienated. When Ambler grew middle

aged he wrote about middle aged fellows with dodgy money

in the bank who had their fair bit of fit pussy and

chicanery. Some of these later efforts, like The Night

Comers and Journey Into Fear, were tight pieces of

fiction. He was no longer in the same league as Graham

Greene or Len Deighton; later Ambler is like early

Frederick Forsythe. The heroes can be somewhat shifty,

semi-comic, English men, sometimes overweight but always

with a taste for brassy women. Later Ambler is nastily

anti-Islamic, though sharp as ever in his perception of

exactly what Islamic fundamentalism was, given that

I’m talking about novels written in the early

sixties.

Where once he delivered books eagerly awaited by

intelligent Hollywood, now his work seemed to be packed

full of putative starring roles or lucrative cameo

appearances for cynical Swinging Sixties quality hacks

like Richard Harris, Sophia Loren, Michael Caine, or Rod

Taylor. There was a lot of square stuff about the younger

generation going to go go parties, older chaps in dinner

jackets getting ready for cocktail parties attended by

air hostesses and traveling salesmen. The women can be

Asiatic bitches trying to fulfill the sexual needs of two

masters. One is a badly paid but decent local husband

while the other is the Peter Ustinov-fat Danish manager

at the local canning factory. Women are treated like real

human beings in the early Ambler. Post War Ambler is

loaded down with sexism, crudely displayed in some of his

paperback covers. There are oriental babes, Scandinavian

babes, Communist spy babes, London sluts, and Hollywood

bitches. The heroes are still men without passports or

papers  only

now they provide roles best suited to Robert Morley or

David Niven, not Peter Lorre or Humphrey Bogart.

only

now they provide roles best suited to Robert Morley or

David Niven, not Peter Lorre or Humphrey Bogart.

I sometimes think that the delicacy and accuracy

with which mysoginistic writers observe women is

underestimated. It is certainly an obsession with women,

and perhaps it is the converse, parallel, rather than the

opposite of love. I would hate to be one of those

handsome male writers of boring sensitive shit read

almost exclusively by dumb bitches with large wardrobes

who are that little bit too smart for their local writing

circle. I’m thinking of male model scribblers like

Paul Auster or Bruce Chatwyn.

One of my personal benchmarks for fiction is the

manner in which it deals with women. You can tell a good

writer, male or female, by looking at the way he or she

handles women. Despite many economic and political

changes, it remains the case that the life of a man is so

much easier to write about than that of a woman.

Writers tend to be good at hotels. They end up

spending more time in them than any other sector of

society (other that similarly dysfunctional brothers like

businessmen and traveling salesmen.) What with available

hall porters, whores in the foyer, sluts on the loose,

inevitable voyeurism, hotels are the very stuff of

writing. And not just the Chelsea. My favorite Charlotte

Rampling movie is The Night Porter. Back in those days

Dirk Bogarde was cooler than ever. Later he grew old and

came on all homo.

Me and Frank Digger were involved with a second

hand book business in

I didn’t do all that much traveling in

those days - in fact I’d never been out of Ireland -

but now I do travel all the time so I utilize a slightly

moderated version of that Yank’s philosophy. I agree

with him that reading is about the most secure anchor a

real travelers can carry with him. I do buy the cheapest

editions I can lay my hands on but I tend to dispose of

the whole book at the end of reading , rather than tear

it apart as I go. I remember looking back  guiltily,

having left an old Penguin copy of Gun for Hire by Graham

Greene on a beach on Portugal’s Atlantic coast. Some

of the cheap hotels you stay in like to hold on to

English language editions for the next lonesome drifter

passing through town.

guiltily,

having left an old Penguin copy of Gun for Hire by Graham

Greene on a beach on Portugal’s Atlantic coast. Some

of the cheap hotels you stay in like to hold on to

English language editions for the next lonesome drifter

passing through town.

My pal the writer and performer Kirk Lake told

me one day, when I was buying a load of cheap disposable

paperbacks before I took off on my travels, when he

noticed an Ambler in my pile, that his girlfriend had

been Ambler’s nurse during his last lonely years in

Notting Hill. She told Kirk that he was a very sweet man

to work for.