| THE HANDSTAND | MAY2009 |

Ernie Barnes dies

at 70; pro football player, successful painter

The official artist of the 1984

Olympics in

By Elaine Woo

April 30, 2009

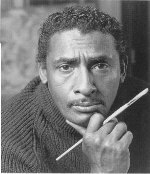

Ernie Barnes, a former professional

football player who became a successful figurative

painter, known for depictions of  athletes and ordinary people

whose muscled, elongated forms express physical and

spiritual struggles, died Monday at Cedars-Sinai Medical

Center in Los Angeles. He was 70.

athletes and ordinary people

whose muscled, elongated forms express physical and

spiritual struggles, died Monday at Cedars-Sinai Medical

Center in Los Angeles. He was 70.

His death was caused by complications of a rare blood

disorder, according to his longtime assistant, Luz

Rodriguez.

Barnes was a

child of the segregated South who transcended racial

barriers to play for the Denver Broncos and San Diego

Chargers before pursuing his real dream: to be an artist.

He became the official artist of the 1984 Olympic Games

in

His style, which critics have

described as neo-Mannerist, became familiar to a prime-time

television audience in the mid-1970s when producer Norman

Lear hired Barnes to "ghost" the paintings by

the Jimmie Walker character "J.J." in the

groundbreaking African American sitcom "Good Times."

As the backdrop for the show's closing credits, Lear used

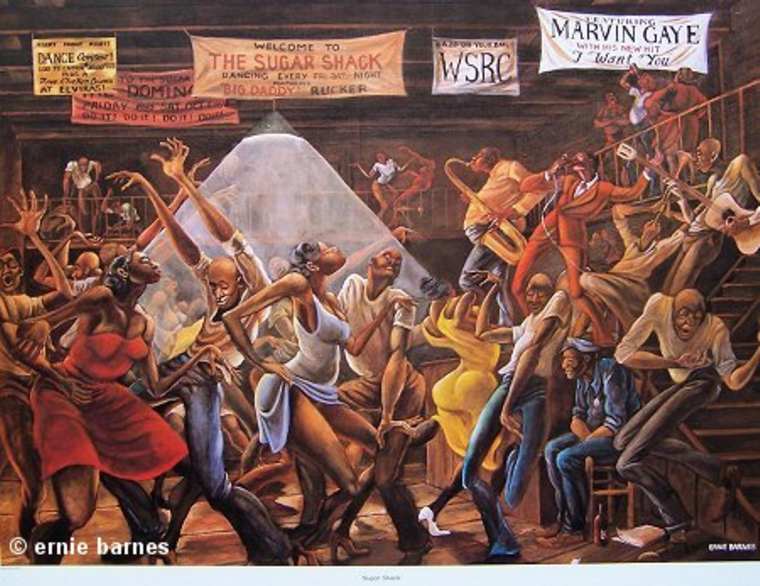

Barnes' 1971 painting "Sugar Shack," his most

famous work. Singer Marvin Gaye later adapted the

painting as the cover art for his 1976 album, "I

Want You."

"Sugar Shack" shows a Brueghel-like mass of

bodies, writhing and jumping to the rhythms in a black

jazz club. There is joy,  tension

and despair in the canvas, which Barnes once said was

inspired by a memory of being barred from attending a

dance when he was a child. As in nearly all of his

paintings, the subjects' eyes are closed, a reflection of

the artist's oft-stated belief that "we are blind to

each other's humanity."

tension

and despair in the canvas, which Barnes once said was

inspired by a memory of being barred from attending a

dance when he was a child. As in nearly all of his

paintings, the subjects' eyes are closed, a reflection of

the artist's oft-stated belief that "we are blind to

each other's humanity."

Singer-songwriter Bill Withers, who was close to Barnes

during the last decade of his life, said the artist often

spoke of wanting to educate people through his art.

"He meant getting people to look past the

superficial into the real vulnerable parts of themselves,"

said Withers, for whom Barnes completed his last major

commission, a painting inspired by Withers' 1971 hit

"Grandma's Hands." "He wanted to help

people peel away that layer of protection that we all

wear to ward off any intrusion into our real private

thoughts. He didn't mind people looking deeper into him.

I found that fascinating."

Barnes was born into a working-class family in Durham, N.C.,

on July 15, 1938. His father was a shipping clerk for a

large tobacco company, and his mother was a domestic for

a wealthy attorney. She brought home books and records

that her employer no longer wanted and used them to

broaden the cultural horizons of her three sons. She

encouraged them to draw pictures from their imaginations

instead of using coloring books. The shy and overweight

Ernie began drawing to escape from the taunts of his

schoolmates.

He was still chubbier than most kids when he reached high

school, but a teacher there helped him turn his size into

advantage.  He started lifting

weights, lost his extra pounds and began excelling on the

playing field. He became captain of the football team and

by graduation had scholarship offers from 26 colleges.

He started lifting

weights, lost his extra pounds and began excelling on the

playing field. He became captain of the football team and

by graduation had scholarship offers from 26 colleges.

He chose North Carolina College (now North Carolina

Central University), a historically black institution in

Durham, where he played football and majored in art. He

left before graduating in 1960 to turn pro. A 6-foot-3,

250-pound offensive guard, he played for a succession of

American Football League teams, including the Chargers

and the Broncos, for the next five years.

He had kept up with his art when he was playing football,

sketching fellow players, who nicknamed him "Big

Rembrandt." With little money and a family to

support when he left the game, he took a gamble and flew

to Los Angeles with several of his canvases and carried

them on foot several miles to the office of Chargers co-owner

Barron Hilton, who paid him $1,000 for a painting.

After a brief stint as the AFL's

official artist, he met with New York Jets owner Sonny

Werblin, who offered to pay him $15,500 -- $1,000 more

than Barnes had earned in his last season in football --

to develop his skills as a painter for a year. Werblin

was so impressed with Barnes' work that he arranged a

showing for critics at a New York gallery.

After a brief stint as the AFL's

official artist, he met with New York Jets owner Sonny

Werblin, who offered to pay him $15,500 -- $1,000 more

than Barnes had earned in his last season in football --

to develop his skills as a painter for a year. Werblin

was so impressed with Barnes' work that he arranged a

showing for critics at a New York gallery.

Some critics compared him to George Bellows, the American

painter known for his masterful depictions of boxers in

the ring.

Soon Barnes was winning commissions from entertainers

such as Harry Belafonte, Flip Wilson and Charlton Heston.

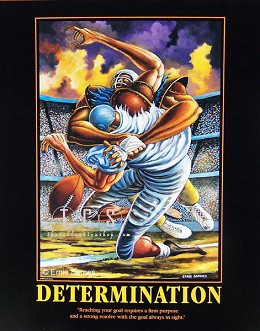

His works from this period were often commentaries on the

brutality of professional football, depicting players

with fangs and other grotesque features. "I was

reaching for the absurdity of what men can be turned into

with football as an excuse," he told Sports

Illustrated in 1984.

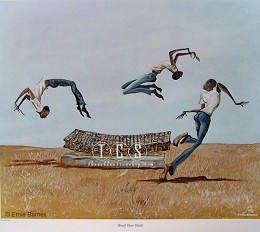

Other paintings captured the powerful grace of youths

playing pickup basketball and the exhaustion of a runner

after a race. His series of Olympics posters were "the

finest, most effective and moving tribute to the Olympics

since the Greeks stopped painting their athletes . . . on

black or red grounds," critic Frank Getlein wrote in

a 1989 essay.

Barnes began to expand his subject matter in the early

1970s when he moved to the Fairfax district of Los

Angeles.

Observing the tight-knit Jewish neighborhood provoked in

him a new awareness of black culture and everyday life,

reflected  in "Sugar Shack" and a

traveling exhibition called "The Beauty of the

Ghetto." One of the stops on the tour was the North

Carolina Museum of Art, where years earlier a museum

docent had told Barnes "that black people didn't

express themselves as artists."

in "Sugar Shack" and a

traveling exhibition called "The Beauty of the

Ghetto." One of the stops on the tour was the North

Carolina Museum of Art, where years earlier a museum

docent had told Barnes "that black people didn't

express themselves as artists."

A longtime resident of Studio City, Barnes, who was

married three times, is survived by his wife of 25 years,

Bernie; five children, Sean, Deidre, Erin and Paige, all

of Los Angeles, and Michael of Virginia Beach, Va.; and a

brother, James, of Durham.

A private memorial service will be held at a later date.

Memorial donations may be sent to Hillsides Home for

Children, 940 Avenue 64, Pasadena, CA 91105.

Courtesy of Mikal Muhammad dcy2kinfo@juno.com<dcy2kinfo@juno.com>;

From: Watford, Charles (HHS)

Sent: Monday, May 04, 2009

ARTIST STATEMENT: “From

the beginning, I viewed this painting as a classical

composition of both symbolic and spiritual competition. I

had to be conscious of the symbolism of the game for the

participant as well as the observer. It takes the game

out of the physical rivalry and into the larger context

of the spiritual. The lower portion reflects the

spontaneity of a “pick up game,” the way it may

have been in some part of the country in 1946. Revealed

in the sky above the players is the unfolding of the

dream, an ascension into basketball heaven. The

exuberance of the fans, media and pundits are all part of

the game. The upper portion reveals the way it is today;

the world coming to the NBA. The oval top is reminiscent

of the Gothic arch of cathedrals and Renaissance

architecture, which reinforces the concept of an

aspiration to an ideal goal. From NBA, I created the

mythological “Neba,” Goddess of Basketball. She

carries the championship trophy while holding the rim for

a “Jordanesque” figure about to dunk the ball.

To carry the NBA logo, I employed the use of cherubs,

characteristically portrayed in Renaissance and

mythological art to connote the ideal of supreme

achievement.”