NOVEMBER 2005

El Alto:

A World of Difference

By

Raúl Zibechi | October 12, 2005

americas.irc-online.org

Translated as: El Alto: Un Nuevo Mundo Desde la

Diferencia

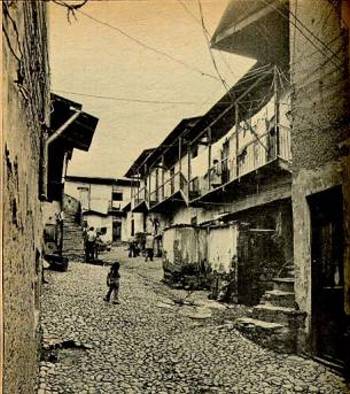

Chaos

in motion. Street vendors, traders, merchants and

stallholders, scouts and agents grind out their insistent

songs. Traffic churns along the black, sticky mud that

overflows sidewalks and streets. Car horns mixed with

Andean music--traditional sounds of the hoarse pututu as

well as electrifying guitars--fuse with voices

offering-selling-demanding-marketing. Hundreds of trucks

prepare to dive into the hole that is La Paz, and a few

others tackle the feat of returning up the interminable

slope: this is La Ceja of El Alto--the political and

commercial center of this Aymara city. A bacchanal of

colors and sounds. As you stand here, adjusting your

senses to the 13,500 foot altitude and icy cold air

blowing off the snowy Cordillera Real mountain range and

taking in the bustle and crowd, the racket begins to take

shape. It is best to let yourself get lost in it all,

until the whirling noises become a murmur, and the din

becomes music. El Alto is chaos, if viewed from the

outside. That is, if viewed from a Western, foreign, or

colonial perspective.

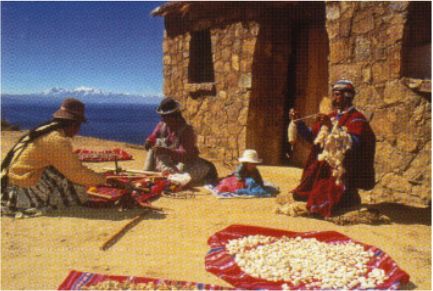

The insurrection of October 2003 that overthrew President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada and tripped up the neoliberal project in Bolivia revealed the existence of an alternative Aymara society that reached its highest point of development in the area surrounding Lake Titicaca and finds its clearest contemporary expression in the city of El Alto. This society has its own political and social institutions, its own economy, and a culture that is clearly distinct from the mestizo-white “official” society built on state institutions and the market economy.

Explosive Growth

El Alto has played an

important role in Bolivia’s social struggles. In

1781, Aymara militias led by Tupac Katari and Bartolina

Sisa established their headquarters in the area, which

was at the time largely uninhabited pampas. From there,

they descended on La Paz, surrounding it for several

months. In 1899, the Aymara people of El Alto established

a human blockade during the Federal War to prevent

constitutional troops from entering. In 1952, it was the

political stage for the definitive triumph of the

national revolution. Since the beginning of this century,

it has been the political center of the Aymaras, the

fastest-growing city in the country, and the most

significant rebel city in all of Latin America.

El Alto has played an

important role in Bolivia’s social struggles. In

1781, Aymara militias led by Tupac Katari and Bartolina

Sisa established their headquarters in the area, which

was at the time largely uninhabited pampas. From there,

they descended on La Paz, surrounding it for several

months. In 1899, the Aymara people of El Alto established

a human blockade during the Federal War to prevent

constitutional troops from entering. In 1952, it was the

political stage for the definitive triumph of the

national revolution. Since the beginning of this century,

it has been the political center of the Aymaras, the

fastest-growing city in the country, and the most

significant rebel city in all of Latin America.

El

Alto has a geographic and strategic advantage over La

Paz, the political and administrative center of the

country. Towering 13,000 feet above sea level, it

controls the slopes and access into the capital, which is

located at 11,800 feet in a deep depression in the earth

where the Spanish decided to build Bolivia’s main

city. From a social standpoint, one could say that on the

Northern Plateau, the poor live above (El Alto) and the

rich live below (La Paz). The Aymaras’ geographic

advantage has played a crucial role in the history of

Bolivia, and continues to play it today.

In 1952, a mere 11,000 people lived in El Alto, making it a basically rural population. By 1960, there were 30,000 inhabitants; in 1976 the figure grew to 95,000. Between 1976 and 1985 (when municipal autonomy was achieved), the population grew explosively--211,000 people in 12 years--due to emigration from mining centers and rural Aymara and Quechua areas of the Northern Plateau, reaching a total of 307,000. By 1992 it had climbed to 405,000 and the 2001 census showed a total population of 650,000; today’s figure is estimated to be near 800,000.

Of this number, 81% identify themselves as indigenous, mainly Aymaras. The city is made up of nine districts, eight urban and one rural, and it can be divided into three zones: the North, populated by migrants of the Northern Plateau where artisan, manufacturing, and commercial work predominate, as seen at the enormous market on July 16th Avenue where some 40,000 market stalls converge; the Central Zone called La Ceja where the principal public services--water and electricity--are located; and the South, where a few factories and migrants from the southern region of the district of La Paz can be found. The airport is inlaid into the middle of the city.

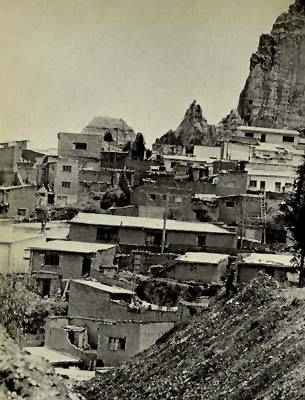

The vast majority of inhabitants of El Alto are poor or very poor, and do not have access to potable water, electricity, health care, education, or housing. El Alto is a precarious city, made up of dusty, irregular streets and adobe dwellings with bricks layered up against them. Its population lives under harsh temperatures that fluctuate, on average, between 14 up to 68 degrees Fahrenheit under the mid-day sun. An additional fact: Sixty percent of the city is under the age of 25.

A Self-Constructed City

This explosive

growth--an average of nearly 10% annually--has left a

large portion of the inhabitants of El Alto without

access to basic services. In 1997, UNICEF estimated that

only 34% of El Alto residents had access to all services,

including paved or cobbled streets, trash pick-up, and

telephone service. In 1992, only 20% of the inhabitants

had access to sewage and 18% to trash pick-up. But in

some districts, those percentages are declining; in the

case of sewage by 2%, while the steps necessary to obtain

it can take up to 10 years. Twenty percent do not have

potable water or electricity, and 80% live on dirt roads.

This explosive

growth--an average of nearly 10% annually--has left a

large portion of the inhabitants of El Alto without

access to basic services. In 1997, UNICEF estimated that

only 34% of El Alto residents had access to all services,

including paved or cobbled streets, trash pick-up, and

telephone service. In 1992, only 20% of the inhabitants

had access to sewage and 18% to trash pick-up. But in

some districts, those percentages are declining; in the

case of sewage by 2%, while the steps necessary to obtain

it can take up to 10 years. Twenty percent do not have

potable water or electricity, and 80% live on dirt roads.

Furthermore, up to 75% of families to do not have any type of health care or medical support, in an area where acute respiratory diseases and diarrhea abound, and infant mortality rates are high. Illiteracy approached 40% at the start of the 1990s, and only 25% of inhabitants had completed high school. In general, services have been constructed by the inhabitants themselves, who formed neighborhood councils that then formed the Federation of Neighborhood Councils of El Alto (FEJUVE, for its initials in Spanish). Today, there are more than 500 neighborhood councils. The councils have taken charge of urban construction, be it directly, through collective works of solidarity, or by pressuring municipal authorities.

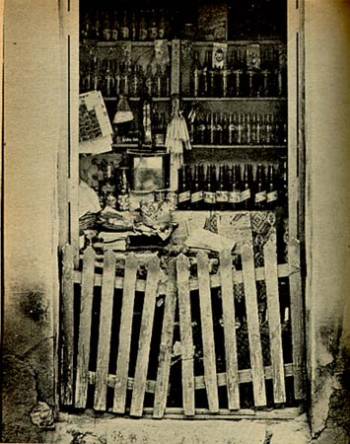

With

regard to jobs, El Alto is characterized by

self-employment. Seventy percent of the employed

population works in family-run businesses (50%), or

semi-business sectors (20%). These jobs are mostly in

sales and the restaurant business (95% of the employed

population), followed by construction and manufacturing.

In these sectors, young people predominate: more than

half of those in the manufacturing sector are between 20

and 35 years of age, the primary factor being the

overwhelming presence of young females in the family-run

and semi-business trade and restaurant sectors.

In El Alto, the principle player in the labor market is the family, both in its role as an employment-generating unit and in its contribution of salaried workers. A new social and work culture has emerged, one marked by job insecurity, instability, and different labor relations--there is no separation between ownership and management of the economic unit and the productive process. In family units, non-remunerated work prevails; family members train each other and hours employed to complete a product is managed solely by workers, so long as they complete the orders on time.

Both the fact that the inhabitants of El Alto have built the city themselves and that they are largely self-employed has led to a very special relation between the people and their environment--they are aware that they have done everything themselves, resulting in a feeling of belonging and high self-esteem.

Organization for Survival and Resistance

The auto-construction of the city and generation of self-employment would not have been possible without a solid organizational base, neighborhood by neighborhood, street by street, market by market. Neighborhood councils have existed since 1957, in spite of the FEJUVE’s more recent inception in 1979. And FEJUVE is not the only organization in El Alto. Mothers’ and youth organizations, cultural associations, migrant centers from different regions, relocated workers’ associations, parents educational associations, and the Regional Workers Center (COR, for its initials in Spanish) all coexist en El Alto.

During the 70s, labor

federations were created for merchants and artisans,

“who, unlike business employees, have a strong

territorial worker identity.” Thus emerged trade

unions and organizations of artisans and vendors, bakers

and butchers, who in 1988 created the COR, now joined by

local bars, guesthouses, and municipal employees. These

groups are mostly made up of small businesses owners and

self-employed workers, a social sector that in other

countries is not usually organized. From the start, the

COR coordinated its actions with FEJUVE--the two being

the most influential forces in the city--playing a

critical role in the founding of the Public University of

El Alto (UPEA) in 2001, and participating in the

uprisings of September-October 2003 and May-June of 2005

that brought down Presidents Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada

and Carlos Mesa.

During the 70s, labor

federations were created for merchants and artisans,

“who, unlike business employees, have a strong

territorial worker identity.” Thus emerged trade

unions and organizations of artisans and vendors, bakers

and butchers, who in 1988 created the COR, now joined by

local bars, guesthouses, and municipal employees. These

groups are mostly made up of small businesses owners and

self-employed workers, a social sector that in other

countries is not usually organized. From the start, the

COR coordinated its actions with FEJUVE--the two being

the most influential forces in the city--playing a

critical role in the founding of the Public University of

El Alto (UPEA) in 2001, and participating in the

uprisings of September-October 2003 and May-June of 2005

that brought down Presidents Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada

and Carlos Mesa.

A

closer look at the neighborhood councils reveals a type

of community organization that in many ways reflects the

traditional organizational patterns of rural Aymara and

Quechua communities. In El Alto the population reproduced

a modified version of the ancestral Andean community. In

recent studies, Aymara sociologist Felix Patzi asked a

fundamental question: “Why do people obey the

organizations when they don’t have to?” Patzi

was referring to the way in which the neighborhood

councils and market labor unions require their members to

participate in the protests, assemblies, and actions they

carry out. To do this, they create filing cards as a way

of keeping track of each family’s participation. The

answer to this question, according to Patzi, is that the

obligatory nature of complying forms part of communal

culture. In the case of rural communities, it is due to

the fact that small subsistence farmers are not

landowners but only have use of the land--and if they do

not comply they can lose access to their only source of

survival.

Patzi identifies three elements in community life in El Alto: the market, land, and education. These are the basis of the validity of the communal structure. In his opinion, a community is characterized by the existence of collective property and private possession of goods. In rural communities, the “good” is land, but in El Alto it is more complex. In trade, “the market stalls are not private property, but rather, are managed by the syndicate, the so-called unions, which is to say that the ownership is collective. The people obey the union because if they cannot sell or trade, they cannot survive.” With regard to land, “decisions about access to water, electricity, propane, and other services are not individual. If you do not comply with the decisions of the council your street will not have sidewalks or water or electricity, because the cooperatives created for services are collective actions that have filled the state deficit.” Last, the parents’ committees control children’s access to education, so participation in assemblies and actions is critical to the future of their children. This set of characteristics is what Patzi calls “obligatoriness,” (obligatoriedad). It does not consist of imposed obligations, but rather, consensual obligations, accepted by a population that feels urban community is a sort of natural extension of rural community and has developed forms of organization to assure survival in a hostile environment.

The neighborhood council calls monthly or semi-monthly assemblies to discuss neighborhood issues. Attendance from one member of each family or household is expected. The councils are organized by geographical zones and to be recognized by the FEJUVE they must have a minimum of 200 members. They are part of “a process of social self-organization of urban zones to debate and attempt to resolve the basic urban needs (potable water, electricity, sewage, attention to health, education, parks, etc.) of the neighborhood population.”

Those who seek to lead the neighborhood council must meet several requirements: a minimum of two years residency in the zone, not be a real estate speculator, merchant, transportation worker, baker, or leader of a political party; he or she cannot be a “traitor,” nor have colluded with dictators.

Pablo Mamani, Aymara director of the Department of Sociology at the UPEA, maintains that the neighborhood councils “have a characteristic similar to rural communities of the Andean world, for their structure, logic, territoriality, and system of organization.” Even though each family owns their own place of residence, there are communal spaces such as plazas, soccer fields, and schools. “In order to buy or sell a lot or house, the family must appear before the neighborhood council to determine whether there are pending debts or some other factor that would prevent the transaction.” In addition, the neighborhood council “is the place to introduce the new neighbor who offers beer in order to be received and accepted.”

Although participation in a neighborhood council is voluntary, “those who do not attend receive social sanctions by way of rumors claiming the neighbor does not respect the neighborhood or the council.” To avoid this negative image, practically all the inhabitants participate in the monthly assemblies. Those who do not attend marches, actions, blockages, or the assemblies receive a fine, which tends to serve as a symbolic punishment. Moreover, the neighborhood council makes a habit of intervening in conflicts and quarrels between neighbors, and in very serious cases, will administer justice with sanctions like community service, which takes it much further than a traditional association and likens it more to agricultural communities. The neighborhood councils are the spinal column of the social movement in El Alto and provide insights into the power of the movement.

Forms of Action of the Urban Community

The neighborhood councils are a form of horizontal organization of the “neighborhood community.” Together they make up extensive networks on the neighborhood and district scale that act without intermediaries, a feature only beginning to appear on the larger scale of FEJUVE. At the level of the FEJUVE, the communal culture dissolves and gives way to the “other” culture--the mestizo-white culture, according to anthropologist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, characterized by clientelism, nationalism, and colonialism. But it is precisely the experience of a horizontal structure “that successfully intensified during the periods of civil uprising in October of 2003.”

The form of mobilization and action of the base communities sheds light on what this social structure is and what it means. To analyze this requires taking a close look at the micro-structures of neighborhood mobilization, since it is during mobilization when their power is deployed and the aspects normally hidden or submerged in everyday life become visible. In general, testimonies and analysis agree that during the rebellion the people went beyond their leaders and the organizations themselves, to the point that several medium-level leaders explained “we were bound by our constituencies.” It was implicit pressure from below, and as such is uncontainable when unleashed. Roxana Seijas, director of FEJUVE, indicates something surprising about the relationship between the base communities and their leaders: “Here at the head and its surroundings, they refer to us leaders as the stuffing.” That is to say that the leaders are superficial, decoration on the cake, but the people expect them to work hard. Her testimony demonstrates two key aspects of communal culture: being a leader is not a privilege, but a service that is never independent of its base, and, and since leaders are “stuffing,” they can be changed for others without causing the organization to fail, and without producing trauma or changes in direction of the organization.

That is how the rebellion “took off without an organizer or leader, and was executed directly by the inhabitants of the neighborhoods and streets;” the neighborhood councils “were not organizing structures of the mobilization, but rather, structures of territorial identity within which other kinds of loyalties, organizational networks, solidarities, and initiatives were deployed autonomously over and above--and in some cases, completely independently of--the neighborhood council.” In many cases, the neighborhood council was merely invoked in a symbolic manner for marches and walks initiated, in reality, by flexible territorial grassroots networks that were created during the actual events, and became “command, deliberation, and decisionmaking structures.”

Something like this can only happen if there already exists, in daily life, the habit of self-organization. These networks were shaped as mobilization committees, Committees for the Defense of Natural Gas, or, on occasion, committees that do not take form through their name, but rather, are simply the natural manner in which inhabitants come together to resolve everyday problems, and at certain moments take on the self-defense of the community.

The assemblies played a decisive role. Building on their ample assembly experience from neighborhood councils, the inhabitants of the neighborhoods came together in informal but massive assemblies that became places for meeting and deliberation, social legitimization and legalization of the movement, and a center for exchanging information. Local radio stations, for their part, strengthened communication on the grassroots level and provided massive cohesion, in particular the Erbol (Radio Education of Bolivia) network, linked to the Catholic Church.

The

ancestral system of shifts that originated in rural

communities enabled  communities

to keep the protestors fed, and maintain road blockages

and near-constant street actions. The system of rotation,

or shifts, is used for all collective actions, from

representation to road blocks, and it consists of

rotating by district or zone, community, and family.

While some members are directly participating, others

rest and attend to their daily lives. For example, in one

zone where 100 inhabitants participate in a road block,

half do a shift from 6:00 in the morning to 3:00 in the

afternoon and the other half does it from 3:00 in the

afternoon till 12:00 at night; after that, the vigil is

voluntary. In this way, everyone participates and while

some are forming a blockade or protesting, others make

food, and prepare to participate in their shift. In

addition, the rotation allows those hundred people to not

have to participate every day, but rather be relieved by

other communities or zones or groups of families. In this

way, each person can directly participate in the street

every few days, or weeks even, allowing the social action

to be maintained indefinitely, thus wearing down the

State and repressive apparatus. In some mobilizations,

like the one that took place in September of 2000, half a

million Aymaras participated through rotation (out of a

total of 1.5 million who live in Bolivia), which reveals

that practically all of the population was involved in

some way or another through this form of non-hierarchical

division of labor.

communities

to keep the protestors fed, and maintain road blockages

and near-constant street actions. The system of rotation,

or shifts, is used for all collective actions, from

representation to road blocks, and it consists of

rotating by district or zone, community, and family.

While some members are directly participating, others

rest and attend to their daily lives. For example, in one

zone where 100 inhabitants participate in a road block,

half do a shift from 6:00 in the morning to 3:00 in the

afternoon and the other half does it from 3:00 in the

afternoon till 12:00 at night; after that, the vigil is

voluntary. In this way, everyone participates and while

some are forming a blockade or protesting, others make

food, and prepare to participate in their shift. In

addition, the rotation allows those hundred people to not

have to participate every day, but rather be relieved by

other communities or zones or groups of families. In this

way, each person can directly participate in the street

every few days, or weeks even, allowing the social action

to be maintained indefinitely, thus wearing down the

State and repressive apparatus. In some mobilizations,

like the one that took place in September of 2000, half a

million Aymaras participated through rotation (out of a

total of 1.5 million who live in Bolivia), which reveals

that practically all of the population was involved in

some way or another through this form of non-hierarchical

division of labor.

Insurrections--Deployment from Below

In the 90s, during the peak of neoliberalism, important changes took place in El Alto. As the above-mentioned social movements grew stronger, a notable change occurred in the political scene. In the 1989 elections, a new party, Conscience of the Nation (CONDEPA, by its Spanish initials) obtained 65% of the votes, surprisingly shunting the traditional parties (MNR, MIR, ADN) to marginal positions. This only happened in El Alto and La Paz, thus revealing the sharp difference in the political behavior of the Aymara people, who had faithfully supported CONDEPA for almost a decade.

CONDEPA was formed by

the popular singer and commentator Carlos Palenque, whose

media outlets--Metropolitan Radio and Channel 4, together

forming the Popular Radio-Television System--were closed

in 1988 by the MNR government. Palenque and CONDEPA were

rejected by the elite white and mestizo middle classes,

who denounced them as “pandering to the people”

and “sensationalist.” Nevertheless, CONDEPA was

the expression of the Aymara poor of both cities, the

sectors marginalized and scorned by the elite. “It

was a party that not only expressed but also defended

Andean reciprocity and culture,” generating citizen

loyalties increased by Palenque’s access to the

media, which he used to denounce “the unjust

prevailing order in the name of those excluded from the

economic, social, political, and cultural arena.”

CONDEPA was formed by

the popular singer and commentator Carlos Palenque, whose

media outlets--Metropolitan Radio and Channel 4, together

forming the Popular Radio-Television System--were closed

in 1988 by the MNR government. Palenque and CONDEPA were

rejected by the elite white and mestizo middle classes,

who denounced them as “pandering to the people”

and “sensationalist.” Nevertheless, CONDEPA was

the expression of the Aymara poor of both cities, the

sectors marginalized and scorned by the elite. “It

was a party that not only expressed but also defended

Andean reciprocity and culture,” generating citizen

loyalties increased by Palenque’s access to the

media, which he used to denounce “the unjust

prevailing order in the name of those excluded from the

economic, social, political, and cultural arena.”

CONDEPA eventually fell into the same game of corruption and clientelism it had denounced and could not recuperate from the death of its leader in 1997, suffering a leadership crisis that led to its political death in the 2002 elections. Nonetheless, it played an important role in the development of the self-esteem of popular Aymara sectors. CONDEPA emerged when the urban Aymara poor were in the full-blown process of self-affirmation, a process that could not have been carried out through the established parties--on the right or left--but rather, by using an “outsider” whom they visualized as part of their cultural world. “The solid constitution of the cultural identity of the inhabitants of El Alto has expressed itself in the collective vote,” says one study on the topic, which reveals that in this city, voting “obeys forms of collective behavior imbued with cultural significance.”

The crisis of CONDEPA is parallel to the rise of the Movement toward Socialism (MAS) and the Indigenous Movement Pachakutik (MIP). Both received strong support in El Alto, and are the parties best connected to these new social actors. By 2003, El Alto’s social movement, which had been fueled by the “water war” in Cochabamba in April of 2000 and the rural Aymara mobilizations in September of the same year, had become the principle actor in the country. On March 5, 2001, FEJUVE backed a protest that had a large impact--especially on the outskirts of the city where people took the streets and avenues and you could see “women sitting in the middle of the street chewing coca leaves and chatting in Aymara and Spanish…” while the main avenues “had become a space for group assemblies where even little boys and girls participated.”

According to Mamani, the tendency to organize by blocks and zones is growing, while during bigger campaigns a sort of “inter-neighborhood reunification with indigenous characteristics” is produced. The pivotal year of 2003 started with strong actions. In La Paz on February 12 and 13 armed confrontations took place between protesting police and the soldiers repressing them, killing 11 police officers and 4 soldiers. Meanwhile, in El Alto a crowd attacked the mayor’s office and Coca-Cola’s facilities, sacking and burning them. It was the second time the El Alto mayor’s office was burned by a crowd, in this case infuriated by the poor management of the MIR mayor. During these days, when the headquarters of the primary political parties (MIR, MNR, AND) and governmental offices were also set on fire, 33 people died in La Paz and El Alto.

On the first of September of 2003, while in

rural areas campesinos protested Chile’s sale of

natural gas, in El Alto a movement began against the Maya

y Paya (“One and Two” in Aymara), tax codes

that would have increased property taxes. On the 15th and

16th, the city was completely shut down and the

population gathered in front of the mayor’s office,

blocking streets in every neighborhood and closing the

principal exits of the city. On the 16th, the mayor

back-pedaled, annulling the tax codes--a resounding

triumph for the social mobilization. But on Sept. 20, the

Warisata Massacre took place, (Warisata was a historic

Aymara ayllu, or school, located in Omasuyos, near Lake

Titicaca), in which four indigenous people and one

soldier died.

On the first of September of 2003, while in

rural areas campesinos protested Chile’s sale of

natural gas, in El Alto a movement began against the Maya

y Paya (“One and Two” in Aymara), tax codes

that would have increased property taxes. On the 15th and

16th, the city was completely shut down and the

population gathered in front of the mayor’s office,

blocking streets in every neighborhood and closing the

principal exits of the city. On the 16th, the mayor

back-pedaled, annulling the tax codes--a resounding

triumph for the social mobilization. But on Sept. 20, the

Warisata Massacre took place, (Warisata was a historic

Aymara ayllu, or school, located in Omasuyos, near Lake

Titicaca), in which four indigenous people and one

soldier died.

In a climate of collective repudiation and indignation, on October 2 a 24-hour protest shut down the streets of El Alto. At Radio Saint Gabriel, the Aymara management--led by Felipe Quispe, director of the rural producers’ organization CSUTCB--carried out a hunger strike. The city became “a structuring factor for the indigenous people of Bolivia,” both in the cities and in the countryside. On October 8, an indefinite strike was declared in El Alto against the sale of natural gas, called for by FEJUVE, COR, and the UPEA. The massive strike could be seen in the occupation of neighborhood territories by inhabitants, who blocked streets and avenues, and dug deep ditches to prevent military trucks and tanks from passing. On the same day, the military opened fire, wounding two young people. The repression grew, causing 67 deaths and 400 wounded; the violence intensified and on Oct. 12 and 13 alone 50 people were killed.

In spite of the militarization of the city and the brutality of the repression, the people of El Alto forced Sánchez de Lozada’s resignation as president. They also put a halt to the sale of gas. What will happen in a country where the people have lost their fear of tanks, violent repression, and massacre? All signs indicate that the future of Bolivia is moving away from the white and mestizo elites and toward the Aymara, Quechua, and other indigenous peoples and the poor.

A Future Full of Surprises

After

October 2003 came the uprising of May-June of 2005. It is

the fifth Aymara  uprising so

far in the 21st century. The first major uprising took

place on April 9, with its epicenter in Achacachi, of the

Omasuyos Province. The second was in September and

October of the same year throughout all of the Northern

Plateau and the Northern Valley of the district of La

Paz. The third uprising lasted almost two months and took

place in June and July of 2001 with its epicenter also in

the large area of the Northern Plateau. The fourth had

its epicenter in El Alto, in October of 2003. Finally,

the May-June uprising also was concentrated in El Alto.

The central demands were the nationalization of

hydrocarbons, a call for a national constituent assembly,

and opposition to the provincial autonomy demanded by the

elite class of Santa Cruz.

uprising so

far in the 21st century. The first major uprising took

place on April 9, with its epicenter in Achacachi, of the

Omasuyos Province. The second was in September and

October of the same year throughout all of the Northern

Plateau and the Northern Valley of the district of La

Paz. The third uprising lasted almost two months and took

place in June and July of 2001 with its epicenter also in

the large area of the Northern Plateau. The fourth had

its epicenter in El Alto, in October of 2003. Finally,

the May-June uprising also was concentrated in El Alto.

The central demands were the nationalization of

hydrocarbons, a call for a national constituent assembly,

and opposition to the provincial autonomy demanded by the

elite class of Santa Cruz.

“Here again the neighborhood councils and labor organizations interact as true neighborhood governments. Decisions are made collectively and publicly by way of neighborhood assemblies. Little by little, the uprising radiates, first into the neighborhoods, and later to other districts and provinces,” maintains Mamani. This time the center was Senkata, a liquid and combustible gas storage plant. There, hundreds of men and women took shifts night and day for 18 days to prevent, in the words of the participants, “not one drop of gas” from going to La Paz and other places.

One of the most

remarkable, and at the same time hopeful, facts is that

all this grassroots activity has been carried out without

the existence of centralized, unified structures. Perhaps

the fact that the Aymara have never had a State has

something to do with it. Nevertheless, the lack of

existence of this type of centralized apparatus has not

minimized the effectiveness of the movements. In fact, it

could be argued that if unified, organized structures had

existed, not as much social energy would have been

unleashed. The key to this overwhelming grassroots

mobilization is, without doubt, the basic

self-organization that fills every pore of the society

and has made superfluous many forms of representation.

For the first time the nucleus of the indigenous movement

is located in a large city where strong urban communities

have emerged. This foretells profound and sweeping

changes in the Bolivian social movement that could very

well radiate out toward other populations in other parts

of the continent.

One of the most

remarkable, and at the same time hopeful, facts is that

all this grassroots activity has been carried out without

the existence of centralized, unified structures. Perhaps

the fact that the Aymara have never had a State has

something to do with it. Nevertheless, the lack of

existence of this type of centralized apparatus has not

minimized the effectiveness of the movements. In fact, it

could be argued that if unified, organized structures had

existed, not as much social energy would have been

unleashed. The key to this overwhelming grassroots

mobilization is, without doubt, the basic

self-organization that fills every pore of the society

and has made superfluous many forms of representation.

For the first time the nucleus of the indigenous movement

is located in a large city where strong urban communities

have emerged. This foretells profound and sweeping

changes in the Bolivian social movement that could very

well radiate out toward other populations in other parts

of the continent.

Raúl

Zibechi is a member of the Editorial Council of the

weekly Brecha de Montevideo, a professor and investigator

of social movements at the Multiversidad Franciscana de

América Latina, and an adviser to various social groups.

He is a monthly contributor to the IRC Americas Program

(online at americas.irc-online.org).

(Translated by Nick Henry)

| For decades, research has been carried out to understand adaptation of human populations to high altitude. A major goal has been to compare how populations with a long history of residence at high altitude and populations with no history of adaptation to high-altitude respond to hypoxia (low oxygen concentration). This research aims to understand the role of natural selection in the adaptation process, and the physiological pathways involved. Two populations that have been commonly studied in this research are the Aymara and Quechua form the Andean Plateau. These populations have been living at high-altitude for more than 10,000 years. Numerous studies have been devoted to the physiological patterns of adaptation to hypoxia of these populations. Many of the aforementioned studies compare the physiological responses to hypoxia of high-altitude natives (e.g. Aymara or Quechua) and low-altitude natives (e.g. Europeans) living at high altitude. However, given the known history of admixture between Europeans and Native Americans in this area, controlling for admixture becomes a critical factor to elucidate the relative role of ancestry vs. developmental influences in adaptation to high-altitude. Traditionally, admixture has been measured indirectly by surname analysis, or skin reflectance. Estimating admixture using genetic markers has been difficult in the past because of the limited number of informative markers available and the expensive and cumbersome genotyping procedures involved. However, the increasing availability of informative genetic markers and the development of powerful, robust and inexpensive genotyping techniques has made possible to obtain much more precise estimates of admixture. |

For

More Information

García Linera, Alvaro (coord.) (2004) Sociología de los movimientos sociales, Diakonía/Oxfam, La Paz.

Gómez, Luis (2004) El Alto de pie, Comuna, La Paz.

Guaygua, Germán y otros (2000) Ser joven en El Alto, Pieb, La Paz.

Mamani, Pablo (2004) Los microgobiernos barriales en el levantamiento de El Alto, inédito.

___________ (2004) El rugir de las multitudes, Aruwiyiri, La Paz.

Quisbert, Máximo (2003) FEJUVE El Alto 1990-1998, THOA, Cuadernos de Investigación No. 1.

Quispe, Marco (2004) De pueblo vacío a pueblo grande, Plural, La Paz.

Rojas, Bruno y Guaygua, Germán (2003) El empleo en tiempos de crisis, Avances de Investigación No. 24, La Paz, Cedla.

Rosell, Pablo (1999) Diagnóstico socioeconómico de El Alto. Distritos 5 y 6, Cedla, La Paz.

Rosell, Pablo y otros (2000) Ser productor en El Alto, Cedla, La Paz.

Rosell, Pablo y Rojas, Bruno (2002) Destino incierto. Esperanzas y realidades laborales de la juventud alteña, Cedla, La Paz.

![]()