october 2004

Some years later I had crossed all the social mores of that little cell of Dublin's literary world of pubs by publishing UP Broadsheets (named in celebration of the grave ticket in James Joyce's Ulysses) poems and prose,some of the contributors were students from University College Dublin and that was forbidden; also I played with my children, (which Paddy maintained was unseen before in Dublin streetscapes); and betimes drank beer with those three good friends, Paddy himself, Professor David Franklin and Paddy Ryan. Paddy had brazenly and correctly tried to prevent me marrying a stupid fellow who fathered my two girls, but he stood by me when I lived alone with them. We would remember then the times he pumped up my bicycle wheels as I frantically bicycled around Dublin several years before from one of my three jobs a day to the other.We would meet on the canal bank as I pushed the old crank along to the corner where I was living on Leeson Street. When I came back from Italy in later years with my two daughters, when it was gossiped that I was "mad", he came to my gate and welcomed me home, and afterwards sent me a guardian, Peter Cohen, whose rule was : "So now, you make her laugh!". A rule he faithfully followed and which enabled me establish an even keel as a lone mother.

It is my sadness that Paddy had died before I got into further publishing and street selling of the Treblin Times. A venture he would have welcomed. Later on, pregnant once more with a new lame-by-night-and-day fellow I ran away from everybody and took lodgings for us in London. I saw no-one. I waited for the birth of my child - I awoke one morning in the Medical Mission of Mary's to find Paddy's wife Kathryn at my bedside, poking my son with a smile on her face. "Here's someone who has been here before,"she said."Now, come back to Ireland." I did.Paddy represented for me the truth of living, I could say things to him I would never utter to others except possibly Patrick Magee,the actor, who gave me a literary education during my existence in London. I felt that none in Dublin paid any attention to the small particulars in life, that Paddy gave particular attention to. He was one whom, as a friend put it recently, thought "there was more to life than life".He turned me on to reading with joy several books he loved for their true gift to literature,Don Quixote and Gil Blas, books I often open and read today. He thought about my little family and he and Kathryn shared their humourous understanding of Dublin life with me. I would not like, now I am in this momentum of memory, to forget to mention James Dwyer who took delivery of all the poems sent in for a competition that Paddy was judging. A sea of papers and envelopes threatening to deluge their very lives i n Heytesbury Lane, where I spent a happy year.Dear Paddy, I did hear your voice once , years after you were dead. I was at a rather large dinner party silently listening to the guffaws of reminiscence about you, and someone then turned on a record of a reading you gave, that soft voice, that loving intonation of the text, the tears ran down my face. Everyone was embarrassed.Jocelyn Braddell, editor

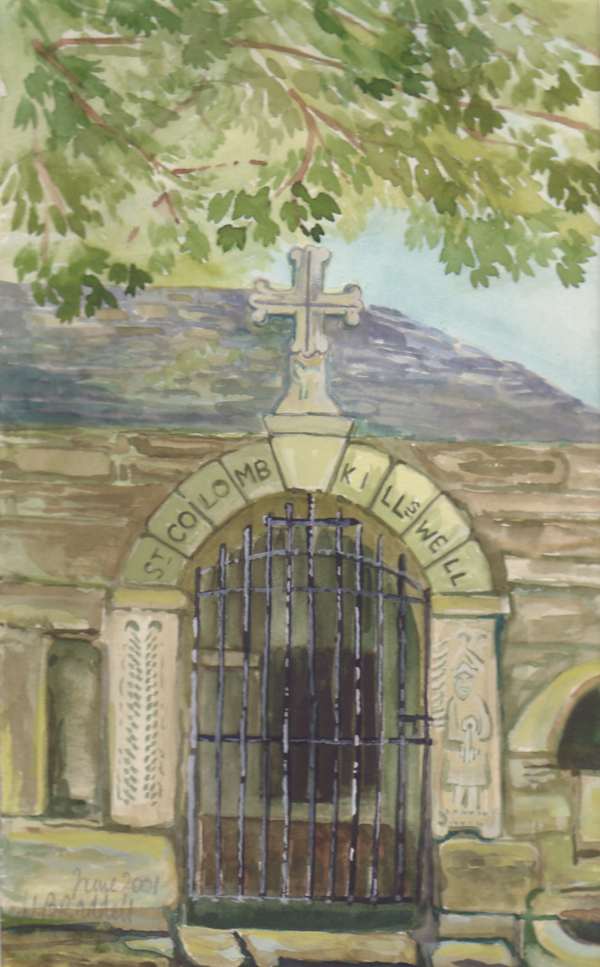

IN PRAISE OF WELLS

Patrick Kavanagh

Ireland of the Welcomes 1959

Patrick Kavanagh (1904-1967) Regarded himself primarily as a poet, but his prose works are far

more numerous than poetry in his

published oeuvre.

more numerous than poetry in his

published oeuvre.Meegan's Well, Cassidy's Well, Feehan's Well - these were famous wells in my youth. They still survive in my imagination as well as in reality, though the well as we know it is giving way to the laid-on supply of water. It is a pity, ofcourse. It is not merely the clear spring water with a possible trout in it for decoration or the thorn-bush overhanging it, but something more. Perhaps the thing I most recall is the gossiping women at the well.

I never liked the chore of walking a crooked path for 500 yards to Meegan's Well, which gave us our regular supply. and I often dreamed that it would be wonderful if there was a spring under our house and we could have a pump in there. Actually there was a powerful spring under the house and in front of it too, but Nicholas Kearney, the water-diviner, was unable to find water anywhere about our house but on the insanitary side of the dung-hill (nowadays known in deference to niceness but not to vividness, as the compost heap.) Not so long ago the present occupiers of that house got another diviner who found the spring mentioned, from which the water is now piped.

Looking at this spring I thought of all the times I carried two tin cans of water from the distant well and I was reminded of a rhyme that was in an old school book:

There was a man who had a

clock, his name was Mathew Mears,

He wound it regularly every day for four and twenty

years;

At length his precious time-piece proved an eight

day-clock to be

And a madder man than Mathew Mears you wouldn't wish to

see.

And so by me and the well. I felt that I had been

put to so much unnecessary work. But it was worth it.

Beautiful things such as wells have ways of surviving.

There is first the idea of a holy well, of which there

are many in Ireland.There has been up to this present day

the belief that it is unlucky to close a well even when

it is in the middle of a field and a hindrance to

tillage. A well so placed has, or had, the privileges of

'lone bush'.

One of the most beautiful of holy wells is Father Moore's

Well beside Kildare Town. One day in the summer of 1954 a

friend who was driving me to Limerick suggested that we

visit this well of which I had not heard before. And

whatever may be the orthodox holiness of it, its natural

beauty flashed into my mind.

The man who told us about the well and the priest after

whom it is named did not know much about Father Moore,

whose biretta and other vestments are to be seen beside

the well. But he did tell us that you couldn't boil the

water, a quality attributed to most dedicated wells, and

which keeps them from being disturbed. The idea of a well

having a dedicated purpose makes it more beautiful than

normally; we see it as beauty must be seen, obliquely; it

enters our mind sideways,shyly.

In the days of my youth, which was still the days of the

horse-drawn vehicle, the eve of the 15th of August was an

exciting time. In my memory are two visions of that hour.

In one we are finishing the cutting of our acre of

conacre oats in the top end of Wood's field. Red Rooney

is finishing the cutting - with a scythe. I remember the

length and texture of that oats because it was an

important evening. I can hear and sometimes see Terry

Lennon getting ready the horse-cart to drive his family

to the well. the rain looks like holding off, though it

was a tradition for it to rain on that evening.

In a short while the cart rattles down the lane loaded

with about six women on two seat-boards, the three back

passengers facing backwards. It took a horse about three

hours to make the journey one way, and that was a long

time to live in the contemplation of nature. That slow

movement taught us something that in after-life we are

apt to run short of, the patience to be alone, the

patience to realise that we live long, not through speed,

but through still contemplation. The proceedings at

Lady's Well in those days were rather rough, but they

exuded sincerity and vital tradition. It was a cultural

entity that was around us there, Lady Well itself is

covered over with a little house and this prevents its

well qualities displaying themselves fully. But it is a

true spring well all the same, and it evokes in my mind a

whole countryside with all its life.

We owe a good deal to Philip

Dixon Hardy for his little book The Holy Wells of

Ireland, which is easy enough to come by. Hardy was a

stupid fellow, not given to analyzing his real motives,

who said that his object in writing was 'to hold up to

the eye of the public the superstitions and degrading

practices associated with them.' In the course of being

angry and self-righteous he gives us a good deal of

information..... He tells us of the pagan origin of well

worship and mentions the Pattern of St Michael's Well,

Ballinskelligs, on the 29th of September, the feast of St

Michael the Archangel, 'which concurs with the autumnal

Equinox and consequently with the Baal Times of the

Druids.' But I do not claim to be a scholar. I only say a

well is a thing of beauty and I am well aware of the high

justice of the fact that the most sacred place of

pilgrimage in Christendom is Lourdes, centered round a

well.

But such considerations are too vague for me. I think of

the common wells again; Tommy Connor's Well was beside

the railway, and Rooney's Well was in a hollow among

blackthorns. As I remember it Mary Rooney (who spoke

Irish) is standing beside the well with a red

handkerchief around her head and she is telling me of the

prophecy that a coach without horses would go along the

road and that it would pass through Owney McGahon's very

house. That was the railway from Iniskeen to

Carrickmacross, not then built, and now closed.

At this point I must remind myself not to be too

generally enthusiastic for all wells. For therein lies

Essayist's Whimsy. Beauty is personal and sometimes of no

interest to others.

However I am glad brought the waters to life

Of wells that were known to me once by taste and by sight

The hawthorn on the flagged roof

Saying here is the place of Love

And you will never get over it quite.