october 2004

- Nuha al-Radi

Born Baghdad, Iraq, 1941. Trained at Byam Shaw School of Art, and Chelsea Pottery, 1961-3. Taught art at the American University, Beirut, 1971-5. Works include important governmental and private commissions. Artwork in private and public collections worldwide including the British Museum, London. Based in Baghdad, but commutes between Baghdad, Jordan, Lebanon and England.

Ode To Nuha - US Depleted

Uranium Takes Another

By Rana El-Khatib

9-8-4

My friend Nuha Al Radi died yesterday

due to complications from leukemia. An Iraqi

national educated in the U.K., she lived between

Iraq and Lebanon. Nuha's end was set into motion

the day President George H. Bush declared war on

Iraq during Operation Desert Storm in 1991.

Thanks to him, a generation of Iraqi citizens

lost their lives, starting with his bombs and

ending with his sanctions. Along the way, Bill

Clinton took the sanctions baton and flippantly

added a bombing raid or two killing many more

innocent Iraqis, before passing it on to George

W. Bush, who is now finishing off his father's

cruel legacy.

My friend Nuha Al Radi died yesterday

due to complications from leukemia. An Iraqi

national educated in the U.K., she lived between

Iraq and Lebanon. Nuha's end was set into motion

the day President George H. Bush declared war on

Iraq during Operation Desert Storm in 1991.

Thanks to him, a generation of Iraqi citizens

lost their lives, starting with his bombs and

ending with his sanctions. Along the way, Bill

Clinton took the sanctions baton and flippantly

added a bombing raid or two killing many more

innocent Iraqis, before passing it on to George

W. Bush, who is now finishing off his father's

cruel legacy.

The U.S., once again, has taken its big, abusive fist and planted it into the pit of my stomach and this time I am an American citizen. The first time I felt America,s merciless blow was in 1986 when Ronald Reagan killed my cousin in Libya just days after I had left her home in Tripoli. One of his F-111 fighter jets dropped a bomb on her parents, home as they slept, snuffing out her young 18 year old life and the lives of all the neighbors I had met only days before.

As the years passed, I have stood helplessly watching American tax dollars, Apaches and F-16s kill Palestinians like flies in support of Israel's brutal occupation. So many innocent people in the Middle East have been killed either directly or indirectly by they U.S., that the pang of loss within me is sometimes easily substituted with loathing. Nuha was an accomplished artist and

author. Her book, "Baghdad Diaries,"

now stares down at me from my bookshelf. I reach

for it, and begin to thumb through its pages. It

opens to Nuha,s hand-written note to me, which

reads, "For Rana, who is an inspiration to

every one - with much love, N."

Nuha was an accomplished artist and

author. Her book, "Baghdad Diaries,"

now stares down at me from my bookshelf. I reach

for it, and begin to thumb through its pages. It

opens to Nuha,s hand-written note to me, which

reads, "For Rana, who is an inspiration to

every one - with much love, N." - Nuha found something inspiring in everything she saw and touched - no matter how mundane or uninspiring it seemed to most. I race through my e-mail exchanges with her. I catch myself contemplating writing to her as though an e-mail from me might awaken her from her eternal sleep. I read and re-read her last e-mail to me, dated August 5, 2004.

- She seems so alive and hopeful -

"France is lovely. Just had my new blood

count done today and I am holding steady. So if

it continues, that's great, but I still keep

fingers and toes crossed, have a long way to go

still," and she ends with her signature

"Love N." Her words take on new meaning

now that I know I will never again get another

Nuha e-mail. Reality is a hard pill to swallow.

I knew Nuha only for a short while. But

during that time, I grew to love her so very

deeply. She was unique, caring and had a style

about her that was all her own. In Nuha, there

was a distinctive human with boundless energy and

creativity. She saw art in every day objects.

What people often discarded, she would pick up

and turn into whimsical figures that were

exclusively 'Nuha'.

I knew Nuha only for a short while. But

during that time, I grew to love her so very

deeply. She was unique, caring and had a style

about her that was all her own. In Nuha, there

was a distinctive human with boundless energy and

creativity. She saw art in every day objects.

What people often discarded, she would pick up

and turn into whimsical figures that were

exclusively 'Nuha'.

Nuha was never unrealistic. Unlike myself, she accepted reality and dealt with its blows. But she also relished life's magnificent moments. Nuha was always comfortable in her own skin, and her resilience was to be envied.

As I flip though her book, I am comforted just a little by her humor and matter-of-fact writing style as she describes the horrors of the bombs that tore her beautiful country apart in 1991. My eyes fall onto page 18:

Day 10 - I say, "Read my Lips",

today is the tenth day of the war and we are

still here. Where is your three to ten days swift

and clean kill? Mind you, we, are ruined. I don't

think I could set foot in the West again. If

someone like myself who is Western educated feels

this way, then what about the rest of the

country?

I can almost hear her English accent utter the words in her own Nuha way. And then I remember

the first time I sat down to play Scrabble with

her at my Uncle's home in Lebanon. I figured we

would have fun, but I had no idea who I was up

against. She started to put down the letters

'I.N.E.R.' and all I could think was, "What

is an 'iner'? But she kept going, and finished

off the word with 'T.I.A.' I looked at the word

again, and then back at her letter rack, and

realized that all her letters were gone! She

opened with the word INERTIA beginning with a

score of over 150 points. I knew I was in trouble

at that point. "Inertia?!" I protested

incredulously - "How did you come up with

'inertia'?!" She just smiled in her own

gentle way, and disparaged her far superior

skills with a good-natured retort, "Well,

that was the only word I could come up

with."

remember

the first time I sat down to play Scrabble with

her at my Uncle's home in Lebanon. I figured we

would have fun, but I had no idea who I was up

against. She started to put down the letters

'I.N.E.R.' and all I could think was, "What

is an 'iner'? But she kept going, and finished

off the word with 'T.I.A.' I looked at the word

again, and then back at her letter rack, and

realized that all her letters were gone! She

opened with the word INERTIA beginning with a

score of over 150 points. I knew I was in trouble

at that point. "Inertia?!" I protested

incredulously - "How did you come up with

'inertia'?!" She just smiled in her own

gentle way, and disparaged her far superior

skills with a good-natured retort, "Well,

that was the only word I could come up

with."

The most 'Nuha-esque' image that will forever be imbedded in my mind will be the fresh flower or two which always adorned her full head of black hair, poking out above her ear. They never seemed to fall or waiver from their spot above her warm, smiling face.

Three weeks prior to her passing, I mailed to Nuha at her sister,s N.Y. apartment an album of photos I had taken of birds, flowers and my two cats. Nuha loved nature. She loved all animals. And she was always tending to stray cats, dogs or injured birds of the city in which she lived - most recently the feral, often severely injured cats of Beirut. She seemed to enjoy my stories about the animals in my life - the quail in the yard, the hummingbirds I feed, the rabbits. But as luck would have it, my album arrived too late. Nuha had already left N.Y. She never received my little gift. I felt devastated, sensing then she might never see the birds and wildlife I often wrote to her about.

Nuha was killed by America,s bombs dumped on Iraq during the first Gulf War. She was not directly injured upon their impact. Instead, she has become an untallied victim of their carcinogenic aftermath, joining thousands of others who have suffered silently under the thick coat of deceptions about 'smart bombs' and 'limiting collateral damage.' As though foreseeing her own fate, Nuha makes reference throughout her book to the rampant grave illnesses that afflicted Iraq's citizens following Desert Storm, as she did on this particular entry on page 16.

15 November 1994 - Everyone seems to by dying of

cancer. Every day one hears about another

acquaintance or friend of a friend dying. How

many more die in hospitals that one does not

know? Apparently, over thirty percent of Iraqis

have cancer, and there are lots of kids with

leukaemia.

According to reputable sources, of the 580,400 soldiers who served in the first Gulf War, 11,000 are now dead. By 2000, 325,000 U.S. soldiers who served in the Gulf were on medical disability - a mere 13 years after being on combat duty.[1] Imagine then the ravages inflicted upon Iraq's population who did not have the option to leave.

The depleted uranium left by the U.S. bombing campaign has turned Iraq into a cancer-infested country. For hundreds of years to come, the effects of the uranium will continue to wreak havoc on Iraq and its surrounding areas.

If no one in the White House and Congress cares to speak out against the murder of millions of Iraqis, then perhaps someone might want to consider the harm the U.S. military has inflicted upon its own soldiers as a result of its brutal actions in Iraq. On page 41 of Nuha's book, she captures very eloquently her own feelings of exasperation toward Washington and its horrific policies:

Day 34 - What a brave man, [President

George H. Bush] passes judgment on us while he

plays golf far away in Washington. His forces are

annihilating us. I find it very difficult to

believe that we have been so discarded by

everyone, especially the Arabs. I presume that

this war will be the end of so-called Arab unity

- that was a farce even while it lasted. We had a

super barbecue lunch today. A lovely day, but

quite noisy - the racket is still going on even

now at midnight. I can't stand the Voice of

America going on

about American children and how they are

being affected by this war. Mrs. Bush, the so

called humane member of that marriage, had the

gall to say comfortingly to a group of school

kids, "Don't worry, it's far away and won't

affect you." What about the children here?

What double standards, what hypocricy! Where's

justice?

about American children and how they are

being affected by this war. Mrs. Bush, the so

called humane member of that marriage, had the

gall to say comfortingly to a group of school

kids, "Don't worry, it's far away and won't

affect you." What about the children here?

What double standards, what hypocricy! Where's

justice?

Nuha ends her book with the following statement:

Being the eternal optimist, I can only pray and hope that war can be avoided.

The U.S. has killed yet another innocent and peaceful person. Nuha is gone, following in the footsteps of millions that have passed before her, paving the way for millions to follow. Iraq is not as far away as Ms. Bush and family like to believe. Sooner or later, the murderous consequences of America's actions will catch up with us - all of us. For now, however, I mourn the loss of my friend Nuha - alone. - ____

- Rana El-Khatib is an author living

in Phoenix, Arizona. She is the author of the

collection of political poetry, BRANDED: The

Poetry of a So-Called 'Terrorist', which, along

with Nuha Al Radi's "Baghdad Diaries"

can be found at www.amazon.com. The author can be

reached at brandedpoetry@yahoo.com.

Rense.com

In Gaza, Israeli brutality on display dailyby Rana El-Khatib

25 January 2004

"Israel good!" were the last words my husband and I heard as we left the final checkpoint within Erez, the border crossing maintained by Israel to control all entries and exits to and from Gaza.

I turned back to get a closer look at the soldier. I saw a petite, attractive blonde, her face almost smiling. Her arms rested comfortably on a large-against-her-frame M-16. Her words echoed chillingly in my head – not because I did not want to believe her, but because I had just seen the other side of Israel: the "not-so-good" Israel.

We traveled to Gaza to return 6-year-old twin sisters, Asma and Hiba, to their refugee camp existence. The girls had spent the last five months in our Phoenix home recovering from major surgery. They had grown very fond of their doctors and the dozens of families they met here.

They also grew accustomed to the creature comforts of American life. Here, they had a soft bed. They could sleep the night through without the earsplitting sounds of artillery all around them. They had a television. They showered every day and enjoyed a tub filled with warm suds. They did not have to fear a helicopter. They had electricity all the time. They could be children.

In Gaza, they sleep on mats on the floor. They shower only when they have water. A helicopter sends them into a panic. Their father is not always able to travel to his nursing job. Electricity cuts off regularly. A soldier represents terror and hate. They are denied a childhood as we know it.

Our four disturbing days and three sleepless nights in Gaza were filled with the images and sounds of a society in turmoil. Atrophy infested every aspect of life, and a real sense of isolation hung in the air.

During the daylight, in the company of friends, we tried to overlook the dilapidated conditions. During the nights, it was a different story. Trying to sleep amid the raucous sounds of state-of-the-art Israeli weapons against the pathetic pap, pap, pap of Palestinian Kalashnikov guns was difficult.

At times, only a few rounds could be heard echoing above the city. At other times, my husband and I cringed helplessly at the thought of who was at the receiving end of the hail of bullets. When the shooting began, it silenced the cacophony of roosters crowing out of sync and the sporadic, spine-chilling shrill of hawks that pierced the dark.

And at least once each night, there remained one sound that jolted me back to consciousness – the vociferous brays of one anguished donkey. Every species seemed troubled.

Our ninth-floor room in our empty hotel offered a panoramic view of two very disparate worlds. Immediately below us, we could see the decrepit Palestinian world. In the distance, a settlement that might as well be labeled "Jews Only" nestled up neatly against the seashore, enclosed behind lush greenery and protected by armed soldiers in watchtowers.

When I asked if I could take photos, I was told simply, "The Israelis will see you and you could get shot." The bullet hole in our hotel window and rear wall facing it reinforced the wisdom of their recommendation.

Bullets also occasionally rain down from dreaded Israeli observation towers. These blots on the landscape protrude menacingly over the densely populated towns. And when the volleys of bullets hail down, for whatever given reason, they often kill or injure innocent people going about their daily lives, such as the life of 9-year old Hani.

We saw his lifeless and bloodied body at a hospital morgue. He had been shot in the head by one such bullet while playing soccer.

Israeli soldiers interfere with the most basic of freedoms, like the choice to leave one's home. When Palestinians are not jailed in their homes under curfew, their freedom is restricted by notorious checkpoints that can take anywhere from 15 minutes to 15 hours to cross.

At these checkpoints, soldiers peer out through small, darkened, rectangular windows from inside unsightly steel structures that overlook pothole-filled roads. Decisions as to who goes in and out of particular areas are often arbitrary and baseless.

Merkava tanks also dominate the society. Concealed inside 3-inch walls of steel, Israeli soldiers barrel forebodingly down small, densely populated streets. The tanks deliberately damage streets, churning the asphalt into crater-filled, sewage-seeping obstacle courses for emaciated donkeys and the relatively few cars to maneuver precariously around.

Soldiers will sometimes park the steel behemoths in one spot, shifting their cannons from side to side, provoking the young and the fearless to throw rocks at them. Consequently, the soldiers open fire into the crowds, leaving both destruction and death in their wake.

F-16 fighter planes serve as yet another notch in the belt of Israeli domination, reinforcing their total control over the Palestinians they rule. They streak sinisterly across the Gazan sky – day and night. Heaps of mangled concrete buildings lay in their wake.

The most spine-chilling face of Israel's occupation comes in the form of Apache helicopters. The mere sight of one causes pandemonium in the streets. People scramble to take cover. No one feels safe. Apache missions almost always set out to murder individuals who are unilaterally declared to be "threats to Israel's security."

In the process of executing people without any due process, innocent bystanders are killed as well. They were either unfortunate enough to be in the area when the assault took place, or were administering aid to the victims of the initial onslaught. These innocent human beings get tacked onto the mounting "collateral damage" pile.

Among Israel's most provocative actions is its ongoing expansion and development of new government-subsidized Jews-only housing for illegal settlers to live on stolen Palestinian land. These settlers drive on Jews-only roads that lead into lavish Jews-only colonies with manicured lawns and swimming pools. Palestinians, less than one mile away, do not even have enough clean water to drink.

Perhaps the most egregious act of Israel's occupation that we saw firsthand is its home demolitions and collective punishment policies. Thousands of homes and apartment buildings have been demolished. Entire families are forced into tents set up by the United Nations, making refugees of refugees for a second, third and even fourth time. It is estimated that some 40,000 Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank have been left homeless since September 2000.

We returned precious Asma and Hiba to a giant prison cell. Their crime is that they refuse to disappear silently into someone else's version of history and fact. Palestine may have been erased off the world's maps, but Palestinians have not. Asma and Hiba have not. At least not yet.

El-Khatib is a Palestinian-American poet and activist living in Phoenix. She is the author of BRANDED, The Poetry of a So-Called “Terrorist,” a collection of poems available from online booksellers beginning in March 2004. She can be contacted at brandedpoetry@yahoo.com.

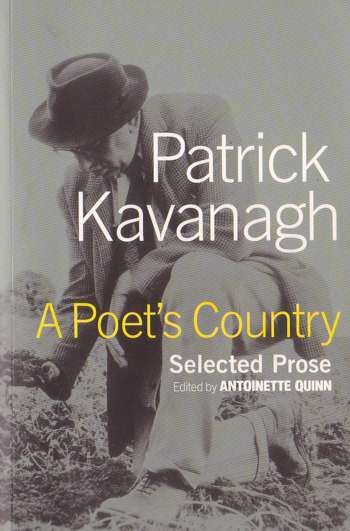

When you go to Lough Derg, by Patrick Kavanagh

It is to be regretted that sinners don't come to Lough Derg anymore. As one of the priests on the island said to me, when a modern man sins now he doesn't believe in sin. He rejects the fundemental fact of sin. the ethic has been torn up by the roots. And yet even then there is something in men which compels them to dredge in the harbours of the soul in self-denial. Lough Derg is above everything else a challenge to modern paganism. If a man brings his pride with him there is sure to be a fierce battle. the only thing that disturbed me on Lough Derg was the absence of obvious mental or spiritual struggle. I like dramatic conflict, the inner convulsions that erupt the burning lava of the soul through the crust of piety.