october 2004

A Reckoning With History

The Washington Post Company

By W. Richard West Jr.

The

opening of the National Museum of the American Indian on

Tuesday speaks eloquently to the poetic possibilities of

history. With this

The

opening of the National Museum of the American Indian on

Tuesday speaks eloquently to the poetic possibilities of

history. With this

powerfully symbolic act, the history of the Americas will

have circled back

on itself to a point of reckoning and resolution five

centuries in the

making. The hemisphere's first citizens will have a

commanding presence in

the political center of the nation, occupying the last

site on the hallowed

grounds of the Mall next door to the Capitol itself.

I cannot contemplate this long journey through the

shadowed valleys of

American history without remembering, as its very

personification, the life

of my late Southern Cheyenne father, Dick West. He was

born in 1912 in

Darlington, Okla., during the nadir of Southern Cheyenne

cultural life. It

had been shattered by the wars of the 19th century and

the annihilation of

the great buffalo herds. At 6 he was forcibly removed

from his parents' home

and sent to federal boarding schools, where he was

dressed in a military

uniform, his long hair was cut and he was prohibited from

speaking Cheyenne.

He remained there for the next 15 years and was trained,

finally, to be a

bricklayer and carpenter, notwithstanding his obvious

gifts as an artist and

his knowledge of traditional Plains art.

Despite these compromised beginnings, my father

ultimately triumphed in a

long and productive life, passing away at 83 in 1996,

well into my tenure as

director of the National Museum of the American Indian.

He remained proudly,

almost fiercely, Cheyenne all his days. In his twenties

he worked hard to

graduate from college when most American Indians did not,

and later he

became the first Native person to receive a graduate

degree in fine arts

from the University of Oklahoma. He became a famed Native

artist and major

figure in the 20th-century Native fine arts movement. A

college teacher, he

taught generations of Native artists who literally have

defined the field in

this century and the one past.

As the museum opening approaches, I often contemplate my

father's life as a

profound, indeed defining, example for me. He worked with

determination to

ground me in the Cheyenne culture that for him had been

retained against the

explicit and oppressive policies of federal

"de-culturalization" he had

faced. To honor him and his hard-won wishes for me, I,

too, have remained a

Southern Cheyenne all of my life. Two years ago I was

asked to join the

Southern Cheyenne Society of Chiefs, which oversees the

ceremonial life of

the tribe, and to sit in council where my

great-grandfather Thunderbull and

my great-uncle Elliott Flying Coyote sat before me.

But my father also believed, almost adamantly, that I

should prepare,

through education, for what he believed would be the

future of the Southern

Cheyenne: a future not held back by cultural insularity.

After college and

graduate school, I trained as an attorney and represented

American Indian

tribes before the courts and Congress for many years

before becoming

director of the National Museum of the American Indian a

decade and a half

ago.

On a far larger, hemispheric canvas, the museum, through

the eyes of Native

peoples themselves, will give voice, in exhibition and

program, to these

same stories of cultural challenge, resilience and

survival. The stories

tell of enduring values, long held, that have centered

the spiritual and

cultural lives of the Native communities of the Americas

for the millennia.

They address candidly the devastating impact of the

European encounter and

the social and cultural destruction that resulted. They

proclaim, however,

with pride and truth looking to the future, the cultural

constancy of

21st-century Native communities in the Americas and their

steadfast refusal

to become mere ethnographic remnants of ancient

histories.

In so doing, the National Museum of the American Indian

stands as an

illuminating metaphor for a broader and fundamental

change in the cultural

consciousness of the contemporary Americas. That

consciousness moves to

recognize and respect the place of Native America as the

originating element

of the cultural heritage of all who call themselves

citizens of the

Americas. It also begins to honor, at long last, the

presence and worthiness

of 40 million contemporary indigenous people and hundreds

of Native

communities as essential components of the cultural life

and vitality of the

hemisphere.

I regret deeply that my father will not be with me on

Tuesday. But in

poignant ways, I know he really is -- because his life of

beautiful and

remarkable cultural faith and triumph against daunting

odds is the story of

Native America writ large that lives in the heart of this

museum.

The writer is director of the National Museum of the

American Indian

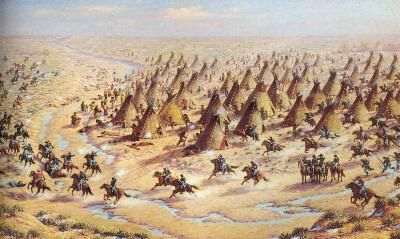

The Sand Creek Massacre

Southern Cheyenne

November 29, 1864

Governor John Evans of Colorado Territory sought to open up the Cheyenne and Arapaho hunting grounds to white development. The tribes, however, refused to sell their lands and settle on reservations. Evans decided to call out volunteer militiamen under Colonel John Chivington to quell the mounting violence. Evans used isolated incidents of violence as a pretext to order troops into the field under the ambitious, Indian-hating military commander Colonel Chivington. Though John Chivington had once belonged to the clergy, his compassion for his fellow man didn't extend to the Indians.

In the spring of 1864, while the Cival War raged in the east, Chivington launched a campaign of violence against the Cheyenne and their allies, his troops attacking any and all Indians and razing their villages. The Cheyennes, joined by neighboring Arapahos, Sioux, Comanches, and Kiowas in both Colorado and Kansas, went on the defensive warpath. Evans and Chivington reinforced their militia, raising the Third Colorado Calvary of short-term volunteers who referred to themselves as "Hundred Dazers". After a summer of scattered small raids and clashes, white and Indian representatives met at Camp Weld outside of Denver on September 28. No treaties were signed, but the Indians believed that by reporting and camping near army posts, they would be declaring peace and accepting sanctuary.

Black Kettle was a peace-seeking chief of a band of some 600 Southern Cheyennes and Arapahos that followed the buffalo along the Arkansas River of Colorado and Kansas. They reported to Fort Lyon and then camped on Sand Creek about 40 miles north.

Shortly afterward, Chivington led a force of about 700 men into Fort Lyon, and gave the garrison notice of his plans for an attack on the Indian encampment. Although he was informed that BlackKettle has already surrendered, Chivington pressed on with what he considered the perfect opportunity to further the cause for Indian extinction. On the morning of November 29, he led his troops, many of them drinking heavily, to Sand Creek and positioned them, along with their four howitzers, around the Indian village.

Sand

Creek Massacre