OCTOBER 2005

The web is our only way to get the news out to the rest of the world.

New Orleans : miscellaneous reports of intrinsic interest reviewed.

Timeline

Friday, Aug. 26: Gov.

Kathleen Blanco declares a state of emergency in

Louisiana and requests troop assistance.

Saturday, Aug. 27: Gov.

Blanco asks for federal state of emergency. A federal

emergency is declared giving federal officials the

authority to get involved.

Sunday, Aug. 28: Mayor Ray Nagin orders mandatory evacuation of New Orleans. President Bush warned of Levee failure by National Hurricane Center. National Weather Service predicts area will be "uninhabitable" after Hurricane arrives. First reports of water toppling over the levee appear in local paper.

Monday, Aug. 29: Levee

breaches and New Orleans begins to fill with water, Bush

travels to Arizona and California to discuss Medicare.

FEMA chief finally responds to federal emergency,

dispatching employees but giving them two days to arrive

on site.

Tuesday, Aug. 30: Mass looting reported, security shortage cited in New Orleans. Pentagon says that local authorities have adequate National Guard units to handle hurricane needs despite governor's earlier request. Bush returns to Crawford for final day of vacation. TV coverage is around-the-clock Hurricane news.

Wednesday, Aug. 31: Tens of thousands trapped in New Orleans including at Convention Center and Superdome in "medieval" conditions. President Bush finally returns to Washington to establish a task force to coordinate federal response. Local authorities run out of food and water supplies.

Thursday, Sept. 1: New

Orleans descends into anarchy. New Orleans Mayor issues a

"Desperate SOS" to federal government. Bush

claims nobody predicted the breach of the levees despite

multiple warnings and his earlier briefing.

Friday, Sept. 2: Karl Rove begins Bush administration

campaign to blame state and local officials—despite

their repeated requests for help. Bush stages a

photo-op—diverting Coast Guard helicopters and crew

to act as backdrop for cameras. Levee repair work

orchestrated for president's visit and White House press

corps.

Saturday, Sept. 3: Bush blames state and local officials. Senior administration official (possibly Rove) caught in a lie claiming Gov. Blanco had not declared a state of emergency or asked for help.

Monday, Sept. 5: New Orleans officials begin to collect their dead.

(Adapted from: Katrina Timeline, http://thinkprogress.org/katrina-timeline/ )

Those are the facts. State and local officials BEGGED for help as people in their city suffered. The Bush administration didn't get the job done and when their failure became an embarrassment they attacked those asking for help.

The New York Times reported on Friday that Karl Rove and White House communications director Dan Bartlett "rolled out a plan...to contain the political damage from the administration's response to Hurricane Katrina." The core of the strategy is "to shift the blame away from the White House and toward officials of New Orleans and Louisiana."

We can't let them get away with this. Please sign our petition today and do your part.http://political.moveon.org/helpvictims/?id=5965-2979492-npagZDFPbLOhBhcRy2M59g&t=4

This is just the first step. We need to continue to help those in need directly and make sure our government does their job. There will be a time to figure out who specifically to blame and what to change. In the meantime, the Bush administration needs to get to work helping those in need.

Thanks for all you do,

THIS IS THE STORY

OF HOW PEOPLE SUFFEREDTrapped in New Orleans by the Flood

-- and Martial Law

BY Larry

Bradshaw and Lorrie Beth Slonsky

www.dissidentvoice.org

September 7, 2005

First Published in Socialist

Worker

Larry Bradshaw and Lorrie Beth Slonsky are emergency medical services (EMS) workers

Two days after Hurricane

Katrina struck New Orleans, the Walgreens store at the

corner of Royal and Iberville Streets in the city’s

historic French Quarter remained locked. The dairy

display case was clearly visible through the widows. It

was now 48 hours without electricity, running water,

plumbing, and the milk, yogurt, and cheeses were

beginning to spoil in the 90-degree heat. The owners and

managers had locked up the food, water, pampers and

prescriptions, and fled the city. Outside Walgreens’

windows, residents and tourists grew increasingly thirsty

and hungry. The much-promised federal, state and local

aid never materialized, and the windows at Walgreens gave

way to the looters.

What you will not see, but what we witnessed, were the

real heroes and sheroes of the hurricane relief effort:

the working class of New Orleans.The maintenance workers

who used a forklift to carry the sick and disabled. The

engineers who rigged, nurtured and kept the generators

running. The electricians who improvised thick extension

cords stretching over blocks to share the little

electricity we had in order to free cars stuck on rooftop

parking lots. Nurses who took over for mechanical

ventilators and spent many hours on end manually forcing

air into the lungs of unconscious patients to keep them

alive. Doormen who rescued folks stuck in elevators.

Refinery workers who broke into boat yards,

“stealing” boats to rescue their neighbors

clinging to their roofs in flood waters. Mechanics who

helped hotwire any car that could be found to ferry

people out of the city. And the food service workers who

scoured the commercial kitchens, improvising communal

meals for hundreds of those stranded.

Most of these workers had lost their homes and had not heard from members of their families. Yet they stayed and provided the only infrastructure for the 20 percent of New Orleans that was not under water.

On Day Two, there were approximately 500 of us left in the hotels in the French Quarter. We were a mix of foreign tourists, conference attendees like ourselves and locals who had checked into hotels for safety and shelter from Katrina.

Some of us had cell phone contact with family and friends outside of New Orleans. We were repeatedly told that all sorts of resources, including the National Guard and scores of buses, were pouring into the city. The buses and the other resources must have been invisible, because none of us had seen them.

We decided we had to save ourselves. So we pooled our money and came up with $25,000 to have ten buses come and take us out of the city. Those who didn’t have the requisite $45 each were subsidized by those who did have extra money.

We waited for 48 hours for the buses, spending the last 12 hours standing outside, sharing the limited water, food and clothes we had. We created a priority boarding area for the sick, elderly and newborn babies. We waited late into the night for the “imminent” arrival of the buses. The buses never arrived. We later learned that the minute they arrived at the city limits, they were commandeered by the military.

By Day Four, our hotels had run out of fuel and water. Sanitation was dangerously bad. As the desperation and despair increased, street crime as well as water levels began to rise. The hotels turned us out and locked their doors, telling us that “officials” had told us to report to the convention center to wait for more buses. As we entered the center of the city, we finally encountered the National Guard.

The guard members told us we wouldn’t be allowed into the Superdome, as the city’s primary shelter had descended into a humanitarian and health hellhole. They further told us that the city’s only other shelter -- the convention center -- was also descending into chaos and squalor, and that the police weren’t allowing anyone else in.

Quite naturally, we asked, “If we can’t go to the only two shelters in the city, what was our alternative?” The guards told us that this was our problem -- and no, they didn’t have extra water to give to us. This would be the start of our numerous encounters with callous and hostile “law enforcement.”

We walked to the police command center at Harrah’s on Canal Street and were told the same thing -- that we were on our own, and no, they didn’t have water to give us. We now numbered several hundred.

We held a mass meeting to decide a course of action. We agreed to camp outside the police command post. We would be plainly visible to the media and constitute a highly visible embarrassment to city officials. The police told us that we couldn’t stay. Regardless, we began to settle in and set up camp.

In short order, the police commander came across the street to address our group. He told us he had a solution: we should walk to the Pontchartrain Expressway and cross the greater New Orleans Bridge to the south side of the Mississippi, where the police had buses lined up to take us out of the city.

The crowd cheered and began to move. We called everyone back and explained to the commander that there had been lots of misinformation, so was he sure that there were buses waiting for us. The commander turned to the crowd and stated emphatically, “I swear to you that the buses are there.”

We organized ourselves, and the 200 of us set off for the bridge with great excitement and hope. As we marched past the convention center, many locals saw our determined and optimistic group, and asked where we were headed. We told them about the great news.

Families immediately grabbed their few belongings, and quickly, our numbers doubled and then doubled again. Babies in strollers now joined us, as did people using crutches, elderly clasping walkers and other people in wheelchairs. We marched the two to three miles to the freeway and up the steep incline to the bridge. It now began to pour down rain, but it didn’t dampen our enthusiasm.

As we approached the bridge, armed sheriffs formed a line across the foot of the bridge. Before we were close enough to speak, they began firing their weapons over our heads. This sent the crowd fleeing in various directions.

As the crowd scattered and dissipated, a few of us inched forward and managed to engage some of the sheriffs in conversation. We told them of our conversation with the police commander and the commander’s assurances. The sheriffs informed us that there were no buses waiting. The commander had lied to us to get us to move.

We questioned why we couldn’t cross the bridge anyway, especially as there was little traffic on the six-lane highway. They responded that the West Bank was not going to become New Orleans, and there would be no Superdomes in their city. These were code words for: if you are poor and Black, you are not crossing the Mississippi River, and you are not getting out of New Orleans.

Our small group retreated back down Highway 90 to seek shelter from the rain under an overpass. We debated our options and, in the end, decided to build an encampment in the middle of the Ponchartrain Expressway -- on the center divide, between the O’Keefe and Tchoupitoulas exits. We reasoned that we would be visible to everyone, we would have some security being on an elevated freeway, and we could wait and watch for the arrival of the yet-to-be-seen buses.

All day long, we saw other families, individuals and groups make the same trip up the incline in an attempt to cross the bridge, only to be turned away -- some chased away with gunfire, others simply told no, others verbally berated and humiliated. Thousands of New Orleaners were prevented and prohibited from self-evacuating the city on foot.

Meanwhile, the only two city shelters sank further into squalor and disrepair. The only way across the bridge was by vehicle. We saw workers stealing trucks, buses, moving vans, semi-trucks and any car that could be hotwired. All were packed with people trying to escape the misery that New Orleans had become.

Our little encampment began to blossom. Someone stole a water delivery truck and brought it up to us. Let’s hear it for looting! A mile or so down the freeway, an Army truck lost a couple of pallets of C-rations on a tight turn. We ferried the food back to our camp in shopping carts.

Now -- secure with these two necessities, food and water -- cooperation, community and creativity flowered. We organized a clean-up and hung garbage bags from the rebar poles. We made beds from wood pallets and cardboard. We designated a storm drain as the bathroom, and the kids built an elaborate enclosure for privacy out of plastic, broken umbrellas and other scraps. We even organized a food-recycling system where individuals could swap out parts of C-rations (applesauce for babies and candies for kids!).

This was something we saw repeatedly in the aftermath of Katrina. When individuals had to fight to find food or water, it meant looking out for yourself. You had to do whatever it took to find water for your kids or food for your parents. But when these basic needs were met, people began to look out for each other, working together and constructing a community.

If the relief organizations had saturated the city with food and water in the first two or three days, the desperation, frustration and ugliness would not have set in.

Flush with the necessities, we offered food and water to passing families and individuals. Many decided to stay and join us. Our encampment grew to 80 or 90 people.

From a woman with a battery-powered radio, we learned that the media was talking about us. Up in full view on the freeway, every relief and news organizations saw us on their way into the city. Officials were being asked what they were going to do about all those families living up on the freeway. The officials responded that they were going to take care of us. Some of us got a sinking feeling. “Taking care of us” had an ominous tone to it.

Unfortunately, our sinking feeling (along with the sinking city) was accurate. Just as dusk set in, a sheriff showed up, jumped out of his patrol vehicle, aimed his gun at our faces and screamed, “Get off the fucking freeway.” A helicopter arrived and used the wind from its blades to blow away our flimsy structures. As we retreated, the sheriff loaded up his truck with our food and water.

Once again, at gunpoint, we were forced off the freeway. All the law enforcement agencies appeared threatened when we congregated into groups of 20 or more. In every congregation of “victims,” they saw “mob” or “riot.” We felt safety in numbers. Our “we must stay together” attitude was impossible because the agencies would force us into small atomized groups.

In the pandemonium of having our camp raided and destroyed, we scattered once again. Reduced to a small group of eight people, in the dark, we sought refuge in an abandoned school bus, under the freeway on Cilo Street. We were hiding from possible criminal elements, but equally and definitely, we were hiding from the police and sheriffs with their martial law, curfew and shoot-to-kill policies.

The next day, our group of eight walked most of the day, made contact with the New Orleans Fire Department and were eventually airlifted out by an urban search-and-rescue team.

We were dropped off near the airport and managed to catch a ride with the National Guard. The two young guardsmen apologized for the limited response of the Louisiana guards. They explained that a large section of their unit was in Iraq and that meant they were shorthanded and were unable to complete all the tasks they were assigned.

We arrived at the airport on the day a massive airlift had begun. The airport had become another Superdome. We eight were caught in a press of humanity as flights were delayed for several hours while George Bush landed briefly at the airport for a photo op. After being evacuated on a Coast Guard cargo plane, we arrived in San Antonio, Texas.

There, the humiliation and dehumanization of the official relief effort continued. We were placed on buses and driven to a large field where we were forced to sit for hours and hours. Some of the buses didn’t have air conditioners. In the dark, hundreds of us were forced to share two filthy overflowing porta-potties. Those who managed to make it out with any possessions (often a few belongings in tattered plastic bags) were subjected to two different dog-sniffing searches.

Most of us had not eaten all day because our C-rations had been confiscated at the airport -- because the rations set off the metal detectors. Yet no food had been provided to the men, women, children, elderly and disabled, as we sat for hours waiting to be “medically screened” to make sure we weren’t carrying any communicable diseases.

This official treatment was in sharp contrast to the warm, heartfelt reception given to us by ordinary Texans. We saw one airline worker give her shoes to someone who was barefoot. Strangers on the street offered us money and toiletries with words of welcome.

Throughout, the official relief effort was callous, inept and racist. There was more suffering than need be. Lives were lost that did not need to be lost.

* Thanks to Alan Maass at Socialist Worker, where this account was first published.Larry Bradshaw and Lorrie Beth Slonsky are emergency medical services (EMS) workers from San Francisco and contributors to Socialist Worker. They were attending an EMS conference in New Orleans when Hurricane Katrina struck. They spent most of the next week trapped by the flooding -- and the martial law cordon around the city.

September 5, 2005 -- Urgent International Appeal. U.S.

troops in New Orleans are

treating hurricane victims as members of "Al

Qaeda." Reports coming to WMR

report that the greater New Orleans area has been turned

into a virtual military

zone where troops threaten bewildered and hungry

survivors who approach them for

help. One resident of the unflooded Algiers section of

New Orleans on the west

bank of the Mississippi River reports that the 65,000

population of the

neighborhood has been reduced by forced evacuations to

2000 even though there

are relatively undamaged schools, parks, and churches

available to house the

homeless. The remaining population of Algiers is in

urgent need of medical

supplies. The same situation exists in Jefferson Parish

and other areas in the

greater New Orleans area. U.S. troops are treating the

remaining people in New

Orleans and its suburbs as "suicide bombers,"

according to the Algiers resident.

FEMA's operations are nothing more than a ruse to

depopulate the poor

African-American and whites from the metropolitan area. A

natural disaster has

now turned into a human rights catastrophe in the making.

Our corporate news

media is totally controlled by the Bush administration

with an information

embargo now in force from the Gulf coasts of Louisiana

and Mississippi. Thecable

news channels are now praising the White House's

response. This is a blatant lie

from a dictatorship that controls the media through

financial control and

intimidation. The web is our only way to get the news out

to the rest of the

world.

*************************************************************

The

Great New Orleans Land Grab

The

17th Street Canal levy was breeched on purpose?

by Ernesto Cienfuegos

La Voz de Aztlan

http://www.aztlan.net/new_orleans_land_grab.htm

Los Angeles, Alta California - September 7, 2005 - (ACN)

There were numerous incidents that occurred during and

immediately after Katrina struck that point to the

"unthinkable". It now appears that a

sophisticated plan was implemented that utilized the

"cover of a hurricane" to first destroy and

than take over the City of New Orleans? As the

world watched the events unfolding, one could not help

think that something was terribly afoot concerning the

rescue by FEMA of the city's poor and predominate Black

population. It seems that a well laid out plan

was put into effect to grab valuable real estate from

well established but

poverty stricken Black families of New Orleans? What

is being implemented

now is nothing less than a sophisticated scheme to purge

and ethnically

cleanse what Whites have termed "Black and 'welfare

bloated' New Orleans".

Among the most telling anomalies pointing to something

terribly afoot is

the gun battle, killing 5, that occurred at the breeched

levy between the

New Orleans Police Department and, what have now been

identified as US

military agents. An Associated Press

report, which has now disappeared,

stated that at least five USA Defense Department

personnel where shot dead

by New Orleans police officers in the proximity of the

breeched levy. A

spokesman for the Army Corps of Engineers said later that

those killed

were "federal contractors" on their way

to "repair" a canal. The

"contractors" were on their way to launch

barges into Lake Pontchartrain,

in an operation to "fix" the 17th Street Canal,

according to the Army

Corps of Engineers spokesman. Deputy Police Chief W.J.

Riley of New

Orleans later reported that his policemen had shot at

eight suspicious

people near the breeched levy, killing five or six.

Who were these "military agents" that

were killed by the police near the

17th Street Canal breeched levy and what were

they doing there? Why did

the New Orleans police find it necessary to shoot and

kill 5 or 6 of them?

No one is saying anything and it appears that the news

story has now been

swept under the rug. Were these US Department of Defense

personnel a

Special Forces group or Navy Seals with top secret orders

to sabotaged the

levy? There are verifiable reports that at least 100 New

Orleans police

officers have disappeared from the face of the earth and

that two have

committed suicide. Could these be policemen that died

defending the levy

against sabotage by "federal contractors"?

Another telling incident that points to a

"nefarious plan" is what New

Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin said at the height of the

crisis. He said

publicly, "I fear the CIA may take me out!"

Mayor Nagin, a Black, said

this twice. He told a reporter for the Associated Press: "If the CIA slips

me something and next week you don't see me, you'll all

know what

happened." Later he told interviewers for CNN on a

live broadcast that he

feared the "CIA might take me out." What does

Mayor Ray Nagin know and why

does he fear the CIA?

In an interview by WWL TV, Mayor Nagin complained

vociferously that

Louisiana National Guard Blackhawk helicopters were being

stopped from

dropping sandbags to plug the levy soon after it

breeched. There is

evidence that no repairs were allowed on the levy

until after New Orleans

was totally flooded!

Many civilian groups who were attempting to aid

people trapped in their

attics, on their roofs and at the Superdome are reporting

that FEMA, other

federal agents and the US military essentially

"stopped" them from doing

so. Convoys that were organized by truckers and

carrying "food and water"

were blocked by agents of the federal government

on the highways and roads

leading to New Orleans. The American Red Cross, in

addition, encountered

numerous incidents and has made formal complaints.

A private ham radio network that deployed throughout the

hurricane

ravished region reported that the airwaves were

being "jammed" making it

impossible to communicate emergency information.

Churches, hospitals and

other essential community groups reported that the first thing that the US

military did, when they arrived, was to cut their

telephone lines and

confiscate communications devices. We all witnessed news reports and heard

statements by flood victims concerning the behavior of

the US military.

Many Black families complained that military

vehicles did not stop to

assist them but just drove by. One news report showed

military personnel

playing cards inside a barrack while Black citizens were

dying of thirst

and hunger.

Today, it is very revealing how the federal

government is handling the

disaster. They want every Black out of New Orleans and

those who insist on

staying in their homes will be removed by force.

The government, through

some media, is utilizing scare tactics to cleanse New

Orleans of all

Blacks. They want no witnesses and this will make the

"land grab" a lot

easier to undertake.

| Re. filthy water with chemicals etc One scare tactic is

calling the flood water "a horrid toxic soup of feces and rotting flesh of corpses". Leaking fuel and other chemicals have created a thin slick floating on the floodwater. Soldiers and police fill the city, moving about in long convoys of military lorries, Humvee jeeps and commandeered buses along streets which are unlit at night because there is no electricity. Police cars cruise by, their lights flashing silently. One police spokesman described Mr Nagin's order to use force to evacuate people as a public relations nightmare. "That's an absolute last resort," Capt Marlon Defillo told the Associated Press news agency. Environmental experts have warned that the planned pumping of New Orleans' contaminated waters into the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain could have damaging effects for years to come. They say the water could kill fish and poison the surrounding wetlands. But Mr McDaniel, secretary of the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, said there was no option but to pump the water straight into Lake Pontchartrain. "It is almost unimaginable the things we are going to have to plan for and deal with," said Mike McDaniel, a Louisiana environment official. Mr McDaniel said reconnecting residents to fresh water mains would take years, and water would have to be brought in. BBC Evacuation 'not disease driven' The evacuation of survivors from storm stricken New Orleans is not justified by the risk of disease from stagnant water, say health experts. They say the threat of outbreaks of diseases such as cholera from the water is low. However, the poor living conditions and difficulty in getting medical care to any who fall sick are reason enough for people to be moved from the area.The city's mayor ordered the forced evacuation of the 5,000-10,000 residents thought still to be living in New Orleans despite the lasting effects of Hurricane Katrina. Mayor Ray Nagin said all citizens except those involved in the rescue effort should leave immediately. Illnesses are probably not justification for an evacuation, but the conditions in which people are living in are certainly much more reason Dr Jean Luc Poncelet of the World Health Organizatio |

The military thugs are now getting tough

with Black families that have owned their old but

beloved homes for many generations. Mr. Rufus

Johnson, a family patriarch who lives in the French

Quarter, said in an interview, "The army has

given me an ultimatum to leave or suffer the consequences

of a forced eviction. I do not understand . My

entire family and I survived Katrina and now they want to

throw me out of the home we have had for generations".

Mr. Johnson lives in a neighborhood where the

flood has subsided and his home is not heavily damaged

yet FEMA wants him out!

The fact that Vice President Dick Cheney is

heavily involved in the FEMA operations from behind the

scenes is very troublesome. Cheney and his cronies at

Halliburton are in line for the lucrative contracts to

"reconstruct a New Orleans". Deals are already

being made with a Las Vegas business group to construct

multi-million dollar casinos in the Big Easy

on prime real estate that was owned by Black families.

Whites throughout history have been notorious

"land grabbers". In the USA they first

confiscated land that belonged to American Indians. Most

of the Indians ended up in worthless tracts of land

called "reservations".

| Bush lifts wage rules for Katrina President signs executive order allowing contractors to pay below prevailing wage in affected areas. By Reuters In a notice to Congress, Bush said the hurricane had caused "a national emergency" that permits him to take such action under the 1931 Davis-Bacon Act in ravaged areas of Alabama, Florida, Louisiana and Mississippi. http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article10218.htm |

*******************************************************

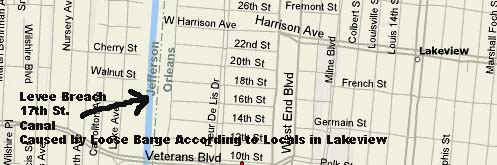

- 17th St. Canal: Locals from Lakeview subdivision of New Orleans report that after Katrina passed a loose barge struck levee causing breach that flooded city.

- WMR has just been informed by

evacuees in Baton Rouge from Lakeview, a

well-to-do New Orleans neighborhood, that the

flooding of the city was caused by a loose barge

striking the levee on the 17th Street Canal. The

breach was not caused by rising flood waters as

reported by FEMA and other agencies. Lakeview is

some 1.5 miles down Veterans Boulevard from the

17th St. Canal

breach.

- Distraught evacuees want to know why the Coast Guard or the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers did not secure the barge. The evacuees who witnessed the barge striking the levee also want to know why the major media is not covering this story. It is not known what company owns the barge.

- September 5, 2005 -- Urgent International

Appeal. U.S.

troops in New Orleans are treating hurricane

victims as members of "Al Qaeda."

Reports coming to WMR report that the greater New

Orleans area has been turned into a virtual

military zone where troops threaten bewildered

and hungry survivors who approach them for help.

One resident of the unflooded Algiers section of

New Orleans on the west bank of the Mississippi

River reports that the 65,000 population of the

neighborhood has been reduced by forced

evacuations to 2000 even though there are

relatively undamaged schools, parks, and churches

available to house the homeless. The remaining

population of Algiers is in urgent need of

medical supplies. The same situation exists in

Jefferson Parish and other areas in the greater

New Orleans area. U.S. troops are treating the

remaining people in New Orleans and its suburbs

as "suicide bombers," according to the

Algiers resident. FEMA's operations are nothing

more than a ruse to depopulate the poor

African-American and whites from the metropolitan area. A natural disaster hasnow turned into a human rights catastrophe in the making. Our corporate news media is totally controlled by the Bush administration with an information embargo now in force from the Gulf coasts of Louisiana and Mississippi. Thecable news channels are now praising the White House's response. This is a blatant lie from a dictatorship that controls the media through financial control and intimidation. The web is our only way to get the news out to the rest of the world.

As a U.S. human rights activist who has reported on genocide in Rwanda, Sudan, West Papua and other parts of the world, I am appealing to my human rights and civil liberties contacts around the world -- Africa, Europe, Latin America, Australia, Canada, Asia and the Pacific -- to immediately bring this humanitarian crisis to the attention of your elected representatives, your governments, and international organizations. They must make immediate demarches to the American diplomatic embassies and offices in your countries. The United States is under the control of a despotic regime that is permitting American citizens and legal residents to die from starvation and disease. This is why the Bush regime refused offers of international assistance -- they are depopulating an entire city that before the storm was 70 percent African American, with the remaining 30 percent largely comprised of those of Creole, French Acadian, and American Indian descent. The United Nations must take this up as an urgent unfolding crisis that has an international impact. Please help our people.

Meanwhile, the communications jamming in the New Orleans area continues. it is now being reported by truck drivers on Interstate-10 as affecting the Citizens' Band (CB) frequencies. ...

September 4, 2005 -- Reports continue that communications in and around New Orleans are being purposely jammed (and severed) by the US government . The jamming is having an adverse impact on emergency, disaster recovery, and news media communications. The jamming is even affecting police radio frequencies in Jefferson Parish, according to an Australian news report.

The President of Jefferson Parish Aaron Broussard told Meet the Press today that FEMA cut his parish's emergency communications lines and he had to have his sheriff restore the severed lines and post armed deputies to ensure that FEMA did not try to cut the communications lines again. Broussard's statement: "Yesterday--yesterday--FEMA comes in and cuts all of our emergency communication lines. They cut them without notice. Our sheriff, Harry Lee, goes back in, he reconnects the line. He posts armed guards on our line and says, 'No one is getting near these lines.'"

Jamming radio and other communications such as television signals is part of a Pentagon tactic called "information blockade" or "technology blockade." The tactic is one of a number of such operations that are part of the doctrine of "information warfare" and is one of the psychological operations (PSYOPS) methods used by the US Special Operations Command. Jamming is currently being used by US forces in Iraq and was used by the US Navy in the botched coup attempt against President Hugo Chavez in April 2002. US Navy ships off the Venezuelan coast jammed diplomatic, military, emergency services, police, and even taxi cab frequencies in Caracas and other large cities.

| Subject: Were the

levees of New Orleans breached on purpose...??? From: nanotechman | All nanotechman's Messages | Date: 9/1/2005 2:02:22 PM ( 9 days ago ) ... viewed 135 times since Feb 20 2005 |

|

September 01, 2005 ... Were the levees of New Orleans breached on purpose after the storm passed ? I used to live in new orleans as I went to school at Tulane Universtiy,and was there last may as I attended the spring session of the American Geophysical Union meeting giving my presentation on x-rays in the solar system ... as a student at Tulane in the early 70's I road my bicycle on those levees ... they were built to withstand such a hurricane and they did ... until only after this storm passed and New Orleans was actually recovering ... I just did an analysis on the breaches and the pattern of breaches is toooooo perfectly placed ... obviously planned locations to flood the city from all sides ... the city was about to recover from the worst hurricane seen in modern times ... my analysis is that the Army Corps of Engineers is the only group capable of placing the destruction of the levees in such a precise pattern and carrying it out to such perfection ... the pattern assured the complete destruction of this vital US city ... a breach in a few places could be dealt with by the cities pump system and it was doing its job ... there is no question that the breaches were placed intentionally to flood from all sides and as I said the only group capable of carrying out this task is the US army Corps of Engineers ... the destruction of NewOrleans was intentional from start to finish and could only be carried out by a group well equipped to do such a job ... jim mccanney |

French QuarterVibrantly coloured buildings stand proudly intact, their wrought-iron balconies having weathered the storm. Even the flowers in the window boxes look healthy. Mildred E Bates looks healthy as well, despite a bandaged finger. She sits on a step looking out at the world, her grey dreadlocks pulled back from her smiling, gold-toothed face. What has she been doing since the storm? "Enjoying being free." Survivor: Mildred Bates BBC

In the historic French Quarter - which

escaped much of the flooding that afflicted areas just a

few hundred yards away - Voodoo Bar owner Gilligan is

wiping down a fridge stacked with bottles of warm beer.

He offers up a toast to "a new beginning". On

Sunday, a defiantly exuberant parade took place on

Bourbon Street. A dozen revellers dressed to the nines

said they were determined to show that life goes on.

Across New Orleans, the adversity has forged a real

community spirit among those determined to stay. Philip

Turner, 62, says he is going shopping. He knows a shop

where tinned food is still on the shelves, waiting to be

claimed. "I've been to Vietnam," he says.

"I know how to survive."BBC

'Times-Picayune' Calls

for Firing of FEMA Chief

Editor & Publisher

Sunday 04 September 2005

New York - The Times-Picayune of New Orleans on Sunday published its third print edition since the hurricane disaster struck, chronicling the arrival, finally, of some relief but also taking President Bush to task for his handling of the crisis, and calling for the firing of FEMA director Michael Brown and others.

In an "open letter" to the president, published on page 15 of the 16-page edition, the paper said it still had grounds for "skepticism" that he would follow through on saving the city and its residents. It pointed out that while the government could not get supplies to the city numerous TV reporters, singer Harry Connick and Times-Picayune staffers managed to find a way in.

It also cited "bald-faced" lies by Michael Brown. "Those who should have been deploying troops were singing a sad song about how our city was impossible to reach," the staffers pointed out. "We're angry, Mr. President, and we'll be angry long after our beloved city and surrounding parishes have been pumped dry."

Here is the text.

***

We heard you loud and clear Friday when you visited our devastated city and the Gulf Coast and said, "What is not working, we're going to make it right."

Please forgive us if we wait to see proof of your promise before believing you. But we have good reason for our skepticism.

Bienville built New Orleans where he built it for one main reason: It's accessible. The city between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain was easy to reach in 1718.

How much easier it is to access in 2005 now that there are interstates and bridges, airports and helipads, cruise ships, barges, buses and diesel-powered trucks.

Despite the city's multiple points of entry, our nation's bureaucrats spent days after last week's hurricane wringing their hands, lamenting the fact that they could neither rescue the city's stranded victims nor bring them food, water and medical supplies.

Meanwhile there were journalists, including some who work for The Times-Picayune, going in and out of the city via the Crescent City Connection. On Thursday morning, that crew saw a caravan of 13 Wal-Mart tractor trailers headed into town to bring food, water and supplies to a dying city.

Television reporters were doing live reports from downtown New Orleans streets. Harry Connick Jr. brought in some aid Thursday, and his efforts were the focus of a "Today" show story Friday morning.

Yet, the people trained to protect our nation, the people whose job it is to quickly bring in aid were absent. Those who should have been deploying troops were singing a sad song about how our city was impossible to reach.

We're angry, Mr. President, and we'll be angry long after our beloved city and surrounding parishes have been pumped dry. Our people deserved rescuing. Many who could have been were not. That's to the government's shame.

Mayor Ray Nagin did the right thing Sunday when he allowed those with no other alternative to seek shelter from the storm inside the Louisiana Superdome. We still don't know what the death toll is, but one thing is certain: Had the Superdome not been opened, the city's death toll would have been higher. The toll may even have been exponentially higher.

It was clear to us by late morning Monday that many people inside the Superdome would not be returning home. It should have been clear to our government, Mr. President. So why weren't they evacuated out of the city immediately? We learned seven years ago, when Hurricane Georges threatened, that the Dome isn't suitable as a long-term shelter. So what did state and national officials think would happen to tens of thousands of people trapped inside with no air conditioning, overflowing toilets and dwindling amounts of food, water and other essentials?

State Rep. Karen Carter was right Friday when she said the city didn't have but two urgent needs: "Buses! And gas!" Every official at the Federal Emergency Management Agency should be fired, Director Michael Brown especially.

In a nationally televised interview Thursday night, he said his agency hadn't known until that day that thousands of storm victims were stranded at the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center. He gave another nationally televised interview the next morning and said, "We've provided food to the people at the Convention Center so that they've gotten at least one, if not two meals, every single day."

Lies don't get more bald-faced than that, Mr. President.

Yet, when you met with Mr. Brown Friday morning, you told him, "You're doing a heck of a job."

That's unbelievable.

There were thousands of people at the Convention Center because the riverfront is high ground. The fact that so many people had reached there on foot is proof that rescue vehicles could have gotten there, too.

We, who are from New Orleans, are no less American than those who live on the Great Plains or along the Atlantic Seaboard. We're no less important than those from the Pacific Northwest or Appalachia. Our people deserved to be rescued.

No expense should have been spared. No excuses should have been voiced. Especially not one as preposterous as the claim that New Orleans couldn't be reached.

Mr. President, we sincerely hope you fulfill your promise to make our beloved communities work right once again.

When you do, we will be the first to applaud.

-------

WALL STREET JOURNAL

By Christopher Cooper (excerpt)September 8th 2005

A few blocks from Mr. O'Dwyer, in an exclusive gated community known as Audubon Place, is the home of James Reiss, descendent of an old-line Uptown family. He fled Hurricane Katrina just before the storm and returned soon afterward by private helicopter. Mr. Reiss became wealthy as a supplier of electronic systems to shipbuilders, and he serves in Mayor Nagin's administration as chairman of the city's Regional Transit Authority. When New Orleans descended into a spiral of looting and anarchy, Mr. Reiss helicoptered in an Israeli security company to guard his Audubon Place house and those of his neighbors.

He says he has been in contact with about 40 other New Orleans business leaders since the storm. Tomorrow, he says, he and some of those leaders plan to be in Dallas, meeting with Mr. Nagin to begin mapping out a future for the city.

The power elite of New Orleans -- whether they are still in the city or have moved temporarily to enclaves such as Destin, Fla., and Vail, Colo. -- insist the remade city won't simply restore the old order. New Orleans before the flood was burdened by a teeming underclass, substandard schools and a high crime rate. The city has few corporate headquarters.

The new city must be something very different, Mr. Reiss says, with better services and fewer poor people. "Those who want to see this city rebuilt want to see it done in a completely different way: demographically, geographically and politically," he says. "I'm not just speaking for myself here. The way we've been living is not going to happen again, or we're out."

Not every white business leader or prominent family supports that view. Some black leaders and their allies in New Orleans fear that it boils down to preventing large numbers of blacks from returning to the city and eliminating the African-American voting majority. Rep. William Jefferson, a sharecropper's son who was educated at Harvard and is currently serving his eighth term in Congress, points out that the evacuees from New Orleans already have been spread out across many states far from their old home and won't be able to afford to return. "This is an example of poor people forced to make choices because they don't have the money to do otherwise," Mr. Jefferson says.

Calvin Fayard, a wealthy white plaintiffs' lawyer who lives near Mr. O'Dwyer, says the mass evacuation could turn a Democratic stronghold into a Republican one. Mr. Fayard, a prominent Democratic fund-raiser, says tampering with the city's demographics means tampering with its unique culture and shouldn't be done. "People can't survive a year temporarily -- they'll go somewhere, get a job and never come back," he says.

Mr. Reiss acknowledges that shrinking parts of the city occupied by hardscrabble neighborhoods would inevitably result in fewer poor and African-American residents. But he says the electoral balance of the city wouldn't change significantly and that the business elite isn't trying to reverse the last 30 years of black political control. "We understand that African Americans have had a great deal of influence on the history of New Orleans," he says.

A key question will be the position of Mr. Nagin, who was elected with the support of the city's business leadership. He couldn't be reached yesterday. Mr. Reiss says the mayor suggested the Dallas meeting and will likely attend when he goes there to visit his evacuated family

Black politicians have controlled City Hall here since the late 1970s, but the wealthy white families of New Orleans have never been fully eclipsed. Stuffing campaign coffers with donations, these families dominate the city's professional and executive classes, including the white-shoe law firms, engineering offices, and local shipping companies. White voters often act as a swing bloc, propelling blacks or Creoles into the city's top political jobs. That was the case with Mr. Nagin, who defeated another African American to win the mayoral election in 2002.

Creoles, as many mixed-race residents of New Orleans call themselves, dominate the city's white-collar and government ranks and tend to ally themselves with white voters on issues such as crime and education, while sharing many of the same social concerns as African-American voters. Though the flooding took a toll on many Creole neighborhoods, it's likely that Creoles will return to the city in fairly large numbers, since many of them have the means to do so.

© 2005 Dow Jones & Company

"Smoking gun" documents nail FEMA, Chertoff, and Bush

Fri Sep 9th, 2005 at 11:03:04 PDT

Rep. Waxman does it again!

He's just posted a letter to Secretary Chertoff from Ranking Member Waxman and Chairman Davis which describes documents from the Department of Homeland Security that show that FEMA was aware in 2004 that a "catastrophic hurricane" could hit New Orleans and "trap hundreds of thousands of people in flooded areas and leave up to one million people homeless." FEMA officials wrote: "the gravity of the situation calls for an extraordinary level of advance planning."

More after the fold...

Sharon Jumper's diary :: ::

Here's the letter that was sent to Chertoff today

The House Committee on Government Reform has obtained from the Department of Homeland Security a document describing the "Scope of Work" of a contract issued by the Federal Emergency Management Agency for the development of a "Southeastern Louisiana Catastrophic Hurricane Plan."

We are writing to request any plans and other documents that were developed under this contract.

FEMA's Scope of Work contemplated that a private contractor, Innovative Emergency Management, Inc. (IEM), would complete the work under the contract in three stages. "Stage One" called for a simulation exercise involving FEMA and the state of Louisiana that would "feature a catastrophic hurricane striking southeastern Louisiana." "Stage Two" called for "development of the full catastrophic hurricane disaster plan." And "Stage Three" involved unrelated earthquake planning.

A task order issued under the contract called for IEM to execute "Stage One" between May 19 and September 30, 2004, at a cost of $518,284. On June 3, 2004, IEM issued a press release announcing that it would "lead the development of a catastrophic hurricane disaster plan for Southeast Louisiana and the City of New Orleans under a more than half a million dollar contract with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security/Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)." A second task order issued on September 23, 2004, required IEM to "complete the development of the SE Louisiana Catastrophic Hurricane plan." The cost of this task order was $199,969.

The "Background" section of the Scope of Work stated that "the emergency management community has long feared the occurrence of a catastrophic disaster," which the document describes as "an event having unprecedented levels of damage, casualties, dislocation, and disruption that would have nationwide consequences and jeopardize national security..."

...According to the Scope

of Work, the contact "will assist FEMA, State, and

local government to enhance response planning activities

and operations by focusing on specific catastrophic

disasters:

those disasters that by

definition will immediately overwhelm the existing

disaster response capabilities of local, State, and

Federal Governments." With respect to

southeastern Louisiana, the specific "catastrophic

disaster" to be addressed was "a slow-moving

Category 3, 4, or 5 hurricane that ... crosses New

Orleans and Lake Pontchartrain." The

Scope of Work explained:

Various hurricane studies suggest that a slow-moving Category 3 or almost any Category 4 or 5 hurricane approaching Southeast Louisiana from the south could severely damage the heavily populated Southeast portion of the state creating a catastrophe with which the State would not be able to cope without massive help from neighboring states and the Federal Government.

The Scope of Work further stated: "The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Louisiana Office of Emergency Preparedness (LOEP) believe that the gravity of the situation calls for an extraordinary level of advance planning to improve government readiness to respond effectively to such an event."

The specific disaster

scenario contemplated under the contract is strikingly

similar to the actual disaster caused by Hurricane

Katrina. The contract envisioned that "a

catastrophic hurricane could result in significant

numbers of deaths and injuries, trap hundreds of

thousands of people in flooded areas, and leave up to one

million people homeless."

The Scope of Work expressly directed the contractor to plan for the following specific conditions:

* "Over one million people would evacuate from New Orleans. Evacuees would crowd shelters throughout Louisiana and adjacent states."

* "Hurricane surge would block highways and trap 300,000 to 350,000 persons in flooded areas. Storm surge of over 18 feet would overflow flood-protection levees on the Lake Pontchartrain side of New Orleans. Storm surge combined with heavy rain could leave much of New Orleans under 14 to 17 feet of water. More than 200 square miles of urban areas would be

flooded."* "It could take weeks to `de-water' (drain) New Orleans: Inundated pumping stations and damaged pump motors would be inoperable. Flood-protection levees would prevent drainage of floodwater. Breaching the levees would be a complicated and politically sensitive problem: The Corps of Engineers may have to use barges or helicopters to haul earthmoving equipment to open several hundred feet of levee."

* "Rescue operations would be difficult because much of the area would be reachable only by helicopters and boats."

* "Hospitals would be overcrowded with special-needs patients. Backup generators would run out of fuel or fail before patients could be moved elsewhere."

* "The New Orleans area would be without electric power, food, potable water, medicine, or transportation for an extended time period."

* "Damaged chemical plants and industries could spill hazardous materials."

* "Standing water and disease could threaten public health."

* "There would be severe economic repercussions for the state and region."

* "Outside responders and resources, including the Federal response personnel and materials, would have difficulty entering and working in the affected area."

It appears that IEM

completed the task order for "Stage One," the

hurricane simulation. An exercise know as

"Hurricane Pam," was conducted by FEMA and IEM

in July 2004, bringing together emergency officials from

50 parish, state, federal, and volunteer organizations to

simulate the conditions described above and plan an

emergency response. As a result of the

exercise, officials reportedly developed proposals for

handling debris removal, sheltering, search and rescue,

medical care, and

schools.

It is not clear, however, what plans or draft plans, if any, IEM prepared to complete "Stage Two," the development of the final catastrophic hurricane disaster plan. The task order for "Stage Two" provided that the "period of performance" was September 23, 2004, to September 30, 2005.

The basis for the award of the planning work to IEM is also not indicated in the documents we received. The task orders were issued to IEM by FEMA under an "Indefinite Delivery Vehicle" (IDV) contract between IEM and the General Services Administration. According to the Federal Procurement Data System, FEMA received only one bid (from IEM) for the task orders.

The documents from the Department raise multiple questions about the contract with IEM and the planning for a catastrophic hurricane in southeastern Louisiana. To help us understand these issues, we request that the Department provide the following documents and information:

(1) Any documents relating to the "Stage One" simulation exercise, including documents prepared for exercise planners and participants, transcripts or minutes of exercise proceedings, participant evaluations, and after action reports;

(2) Any final or draft plans for a catastrophic hurricane in southeastern Louisiana prepared under "Stage Two" of the contract, including any final or draft Catastrophic Hurricane Disaster Plan, Basic Plan Framework, Emergency Support Function Annex, or Support Annex; and

(3) An explanation of the procurement procedures used in selecting IEM for the contract and task orders, as well as a description of IEM's qualifications and the justification for selecting IEM.

We recognize that

Department officials are engaged in ongoing relief

efforts, and we do not want to impair those efforts in

any way. For this reason, we have tailored our

request to the discrete set of documents and information

set forth above. To expedite your response to this

request, we have enclosed copies of the Scope of Work,

task orders, and other documents cited in this

letter.

Sincerely,

Rep. Tom

Davis

Chairman

Rep. Henry Waxman

Ranking Minority Member

WHOOPEE NEWS PUSH

Grätz i-News

Service