september 2004

Bank with close ties to Bush administration engulfed in scandal

By Joseph Kay

24 August 2004

The Justice Department announced on Friday that it is launching a criminal investigation into Riggs Bank. In recent months, the Washington-based bank has become engulfed in a scandal related to charges of money-laundering, corruption and terrorist financing.

Riggs, which touts itself as “the most important bank in the most important city in the world,” has been known for decades as the bank of the Washington elite, including politicians, foreign ambassadors and the wealthy. It has held presidential accounts stretching back to the time of the Civil War, and is a prominent fixture in the political and social establishment of the nation’s capital.

Or rather, it was a prominent fixture. In July, PNL Financial Services agreed to buy Riggs for $779 million. The sale will become final by early next year.

The bank’s prominent embassy and international operations will be shut down in an attempt to bury a scandal that has the potential of becoming much larger. That an institution like Riggs could so quickly disintegrate is an indication of the extent of the corruption that has overtaken American finance and government.

There are three separate activities for which Riggs has come under investigation: (1) its relationship with the Saudi royal family and the potential financing of two of the September 11 hijackers through an account owned by the wife of the Saudi ambassador; (2) its relationship with the corrupt and dictatorial regime of the oil-rich West African country of Equatorial Guinea; and (3) its banking business with the former military dictator of Chile, Augusto Pinochet.

The Saudi accounts

The public revelations concerning the bank’s relationship with Saudi Arabia came mainly through the publication of a Newsweek article on December 2, 2002 (“The Saudi Money Trail”). The news magazine reported that in January 2000, two of the hijackers who were on the plane that crashed into the Pentagon—Nawaf Alhazmi and Khalid Almihdhar—received monetary aid and other assistance from Omar al-Bayoumi.

Alhazmi and Almihdhar are at the center of suspicions of US government complicity in the 9/11 attacks—and for good reason. The CIA had identified the two as early as January 2000 as Al Qaeda operatives, and the Washington Post reported in June 2002 that the FBI also knew of the two from January of 2000. Yet they were allowed to enter the US and live openly in San Diego for 18 months prior to the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington. Newsweek reported in September 2002 that the roommate of Alhazmi and Almihdhar in San Diego was an FBI informant!

According to the December 2002 Newsweek article on Riggs Bank, al-Bayoumi “apparently did work for Dallah Avco, an aviation-services company with extensive contracts with the Saudi Ministry of Defense and Aviation, headed by Prince Sultan, the father of the Saudi ambassador to the United States, Prince Bandar. According to informed sources, some federal investigators suspect that al-Bayoumi could have been an advance man for the 9/11 hijackers, sent by Al Qaeda to assist the plot that ultimately claimed 3,000 lives.”

Al-Bayoumi may have been receiving assistance in his activities from sections of the Saudi royal family. The Newsweek article states: “About two months after al-Bayoumi began aiding Alhazmi and Almihdhar, Newsweek has learned, al-Bayoumi’s wife began receiving regular stipends, often monthly and usually around $2,000 and totaling tens of thousands of dollars. The money came in the form of cashier’s checks, purchased from Washington’s Riggs Bank by Princess Haifa bin Faisal, the daughter of the late King Faisal and wife of Prince Bandar, the Saudi envoy who is a prominent Washington figure and personal friend of the Bush family. The checks were sent to a woman named Majeda Ibrahin Dweikat, who in turn signed over many of them to al-Bayoumi’s wife...”

Dweikat’s husband, Osama Basnan, is reported to be a sympathizer of Al Qaeda and is known to have had friendly relations with the two hijackers, Alhazmi and Almihdhar.

Al-Bayoumi apparently came under suspicion shortly after the attacks of September 11. He was picked up by British intelligence, which found evidence that he had made two phone calls to diplomats at the Saudi Embassy in Washington. However, he was released and is reported to be in Saudi Arabia.

Further, according to Newsweek: “Osama Basnan showed up in Houston last April [2001] while Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah came to town with a vast entourage en route to President George W. Bush’s ranch. According to informed sources, Basnan met with a high Saudi prince who has responsibilities for intelligence matters and is known to bring suitcases full of cash into the United States.”

There are suspicions that Basnan may have been a member of Saudi intelligence, suggesting that Saudi intelligence was closely monitoring, if not aiding, the activity of the September 11 hijackers through its accounts at Riggs.

Newsweek noted that the FBI, as of December 2002, still had an investigation open into the transactions. In July 2003, the FBI accused Riggs Bank of failing to abide by anti-money-laundering (AML) regulations.

Prior to and after the attacks of September 11, it was not unusual for Saudi clients to transfers of millions of dollars in and out of the bank with no questions asked. This was in violation of AML regulations, which require the reporting of all transaction involving such large sums of money.

The bank was eventually fined $25 million in May 2004 for violating these regulations. However, the FBI has issued a statement saying it found no evidence of terrorist financing. The Bush administration has refused to release the intelligence behind the investigation, citing “national security concerns.”

Even after the FBI’s accusations in July 2003, the bank continued to allow massive cash transfers by the Saudi ambassador. Under pressure, the bank announced this past March that it was closing all Saudi accounts.

Equatorial Guinea and General Pinochet

On July 14, 2004, the Minority Staff of the US Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, at the request of Democrat Carl Levin, the ranking minority member of the subcommittee, issued a report that dealt mainly with the bank’s accounts for Equatorial Guinea and Augusto Pinochet.

The report found that “the evidence reviewed by the Subcommittee staff establishes that, since at least 1997, Riggs has disregarded its anti-money laundering (AML) obligations, maintained a dysfunctional AML program despite frequent warnings from OCC [Office of the Comptroller of the Currency] regulators, and allowed or, at times, actively facilitated suspicious financial activity.” The OCC, a branch of the Treasury Department, is responsible for regulating nationally chartered banks.

Equatorial Guinea was Riggs’ largest client. It held over 60 accounts at the bank, with varied holdings of $300-700 million. Its ruler, Teodoro Obian Nguema Mbasogo, came to power in a military coup in 1979 and is infamous for his corruption and brutality. Relations with the United States became strained in the mid-1990s, when the Clinton administration broke off diplomatic ties. However, these were restored by the Bush administration in 2003. The country holds interest for the United States because of its large oil reserves.

Riggs appears to have held both Equatorial Guinea government treasury accounts and the personal accounts of Obiang, his family members, and ministers in his government.

According to the subcommittee report, Riggs “serviced the EG [Equatorial Guinean] accounts with little or no attention to the bank’s anti-money laundering obligations...” For example, “Riggs opened multiple personal accounts for the President of Equatorial Guinea, his wife, and other relatives; helped establish shell offshore corporations for the EG President and his sons; and over a three-year period, from 2000 to 2002, facilitated nearly $13 million in cash deposits into Riggs accounts controlled by the EG President and his wife.”

Riggs also opened an account that received large sums of money from oil companies that did business with Equatorial Guinea, including Exxon Mobil, Amerada Hess, Marathon Oil and ChevronTexaco. Riggs allowed the wire transfer of over $35 million from the account to two unknown companies. “The Subcommittee has reason to believe that at least one of these recipient companies is controlled in whole or in part by the EG President.”

Riggs appears to have acted as a conduit for large-scale bribes or other corrupt machinations between the giant oil corporations and the dictator of a country with which they were eager to do business. The report also noted that these oil companies made a number of large payments (sometimes valued at over $1 million) to individual officials or family members for a variety of services.

The manager of Riggs’ accounts for Equatorial Guinea was Simon P. Kareri, who was eventually fired by the bank in January 2004. According to a bank employee, on more than one occasion Kareri visited the Equatorial Guinean embassy and returned with a suitcase full of $3 million in cash, which was deposited in the bank with no reports to financial regulators.

According to the subcommittee report, “The bank leadership permitted [Kareri] ...to become closely involved with EG officials and business activities, including advising the EG government on financial matters and becoming the sole signatory on an EG account holding substantial funds. The bank exercised such lax oversight of the account manager’s activities that, among other misconduct, the account manager was able to wire transfer more than $1 million from the EG oil account at Riggs to another bank for an account opened in the name of Jadini Holdings, an offshore corporation controlled by the account manager’s wife.”

In addition to its dealings with the Saudi royal family and Equatorial Guinea’s dictator, Riggs had a close relationship with the former dictator of Chile, Augusto Pinochet. Pinochet held numerous active accounts at Riggs between 1994 and 2002, even while he was under house arrest in Britain and his assets were supposedly frozen.

According to the subcommittee report, “The aggregate deposits in the Pinochet accounts at Riggs ranged from $4 to $8 million at a time.... Riggs account managers took actions consistent with helping Mr. Pinochet to evade legal proceedings seeking to discover and attach his bank accounts.... Riggs opened multiple accounts and accepted millions of dollars in deposits from Mr. Pinochet with no serious inquiry into questions regarding the source of his wealth; helped him set up offshore shell corporations and open accounts in the names of those corporations to disguise his control of the accounts; altered the names of his personal accounts to disguise their ownership; transferred $1.6 million from London to the United States while Mr. Pinochet was in detention and the subject of a court order to attach his bank accounts; conducted transactions through Riggs’ own accounts to hide Mr. Pinochet’s involvement in some cash transactions; and delivered over $1.9 million in cashiers checks to Mr. Pinochet in Chile to enable him to obtain substantial cash payments from banks in that country.”

The scope of the corruption, money-laundering and other suspicious activities is indeed astonishing. While it was engaged in these activities, the bank operated under the not-so-watchful eye of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. In spite of clear indications of regulatory violations at least as early as 1997, the OCC took no actions.

Particularly closely involved with the OCC’s investigation into the Pinochet accounts was the comptroller’s examiner-in-charge, R. Ashley Lee, who worked at the OCC from 1998 to October 2002. According to the subcommittee report, “In 2001, [Lee]...advised more senior OCC personnel against taking a formal enforcement action against Riggs, because the bank had promised to correct identified AML deficiencies. In 2002, he ordered examiners not to include a memorandum or work papers on the Pinochet examination to the OCC’s electronic database.”

Lee went to work for Riggs two weeks later, quickly becoming an executive vice president and the chief risk officer. The subcommittee report states: “During his next 18-months at the bank, he attended a number of meetings with OCC personnel related to Riggs’ AML problems,” despite regulations prohibiting former OCC employees from attending meetings on OCC-related maters.

Ties to the Bush family

The revelations of the activities at Riggs Bank demonstrate how commonplace and extensive criminal activity has become within the American financial and political establishment. Not coincidentally, the bank’s activity has a great deal in common with certain features prominent in the Bush administration: the heavy influence of oil interests, the close ties with the Saudi ruling elite, the funding and support given to dictators and former dictators, including General Pinochet.

The relationship of Riggs to the Bush administration is more than tangential. Riggs owns a money management firm, J. Bush & Co., operated by Jonathan Bush, the brother of George H.W. Bush and the current president’s uncle.

Jonathan Bush played a very important role in helping find investors for the various failed oil businesses that George W. Bush ran before he began his career in politics. Jonathan Bush also helped raise money for George H.W. Bush and is a former chair of the New York Republican State Finance Committee. In 2000, he was briefly named president and CEO of Riggs Investment Management Company (RIMCO), a wholly owned subsidiary of Riggs Bank.

While Jonathan Bush appears not to have been directly involved in the Saudi, Pinochet or Equatorial Guinean accounts, his position at Riggs is an indication of the close ties between the bank and the Bush family.

Moreover, Riggs is owned by the Allbritton family, a Texas family with close ties to the Republican establishment. Joe Allbritton, the former head of Riggs who bought the bank in the mid-1970s, is a friend of the Bush family. His son, Robert Allbritton, is the current chairman and CEO.

The Allbritton family is known among the Washington elite for the party it traditionally holds after the annual Alfalfa Club dinner, hosted to mark the birthday of Robert E. Lee, the southern general in the Civil War. The New York Times (“A Washington Bank, A Global Mess,” April 11, 2004) notes, “The Alfalfa roster includes presidents, politicians, diplomats and business impresarios, all bound together by being either formidably influential or fabulously rich. Attendees have included luminaries like Prince Bandar bin Sultan, Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to the United States; Jack Valenti, the president of the Motion Picture Association of America; and others with surnames like Greenspan, Kissinger and Rehnquist. President Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney made their first joint public appearance after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks at the Alfalfa gathering in 2002.”

Valenti, who, like Allbritton and Bush, is a former Texas businessman, is also on the board of directors of Riggs Bank.

A television station also owned by Allbritton was in the news earlier this year after it refused to air an ad critical of the Bush administration’s policy in Iraq.

Perhaps even more than the Enron scandal, the Riggs scandal is a deeply political scandal. No doubt, much of what went on at Riggs remains to be uncovered. With the announced sale of Riggs to PNL, which will be completed by early next year, the owners of the bank are clearly attempting to contain the scandal’s fallout. Forwarded by Robert Nohejl ,The News Report.

Fiat's

Reprieve: Saving the

System, 1979-1987

by Bob Landis

Agent K: “Did he say anything to you?” Officer Edwards: “Yeah, he said the world was coming to an end.” Agent K: “Did he say when?”Men in Black (2001)

Reading the pro-gold

submissions incorporated in the Report of

the U.S. Gold Commission

twenty-some years ago is a humbling exercise. A lot of

those old commentaries could have been written today.

They say just what gold bugs say now: our monetary system

is doomed, and its end will be marked by a major monetary

crisis. The concluding chapter of the Minority Report

(Volume II, Annex A) put it thus:[1]

Should Congress not adopt the recommendations outlined

above, we can expect core inflation rates to rise over

the next decade, and at an accelerated rate – so

that in ten years from now we can expect cheering in the

media when the inflation rate falls below 50%. As

inflation deepens and accelerates, inflationary

expectations will intensify, and prices will begin to

spurt ahead faster than the money supply. / It will be at

that point that a fateful decision will be made –

the same that was made by Rudolf Havenstein and the

German Reichsbank in the early 1920’s: whether to

stop or greatly slow down the inflation, or to yield to

public outcries of a “shortage of money” or a

“liquidity crunch” (as business called it in

the mini-recession of 1966). / In the latter case, the

central bank will promise business or the public that it

will issue enough money to enable the money supply to

“catch up” with prices. When that fateful event

occurs, as it did in Germany in the early 1920’s,

prices and money could spiral upward to infinity and it

could cost $10 billion to buy a loaf of bread. America

could experience the veritable holocaust of runaway

inflation, a cataclysm which would make the Depression of

the 1930’s – let alone an ordinary recession

– seem like a tea party.

Ahem. To state the obvious, the gold

bugs of a generation ago got it wrong. Congress did not

adopt their sound money recommendations, and yet the sky

did not fall, the paper-based system muddled through

famously, and in fact it was gold that entered into a 20

year bear market in dollar terms.

| Axioms of the Global Economic Order By Clif Droke, Gold Strategies Review For years the debate has raged on between the long-term bears and the long-term bulls, those who believe the U.S. stock market and economy is doomed to crash in 1929 fashion, and those who believe the economic outlook brighter for the foreseeable future. At no time in recent years has the debate been as sharp or as acrid as it has this year. Even former bulls have converted and have gone over into the bearish camp in 2004, apparently lulled by the arguments of a global economic slowdown and record levels of debt. It’s amazing what the 10-year cycle can do in the way of influencing investor psychology. This happens every fourth year of every decade -- the last of the long-term holdouts get shaken from the bullish tree and turn bearish. The bears, meanwhile, get even more bearish than normal, which of course paves the way (psychologically) for the big rally that begins typically by the fourth quarter of the X4 year and continues well into the X5 year each and every decade. You can’t have a bull market without a relatively high percentage of angry bears, and this year has given us this much-needed element which will serve as so much rocket fuel for the broad market and economy in the months ahead. Don’t get me wrong. It’s not like I can’t sympathize with all the bearish arguments being bandied around out there. I used to be bearish myself but was brought to see the light in early 2003 after a major long-term pivotal support in the Dow was successfully tested for the fourth time in six years. This, among other observations, proved to my satisfaction that the controllers of America’s financial destiny had no intention of crashing the market anytime soon. This leads me to the subject of this missive, namely, the "Global Economic Order," or GEO for short. That’s just a fancy way of saying "global economy." It should be obvious to anyone who pays attention to world affairs and follows closely the current line of the major corporate and financial interests that a major goal of the money Elites is a fully integrated world economy. And world economy, whether we like it or not, is what we’re going to get before all is said and done. In a nutshell, this is why the bearish argument cannot and will not be allowed to be fulfilled this decade. We haven’t arrived at the long sought-after Elitist goal of Global Economic Order (GEO) yet. There are still Third World countries to be "democratized’ (which means to pave the way for global economic integration). There are still trade barriers to be dismantled. And until the globalization process is complete, America’s financial controllers will not allow the world’s premier engine of economic growth to slide into serious recession, nor will its vital stock market or real estate markets be allowed to crash. It’s that simple, yet the bears keep tripping over the obviousness of it. An Internet friend recently e-mailed me the following observation concerning this failure of the bears to take into account the careful control and manipulation of financial markets: "You’d think these guys who talk nothing but Austrian school economics would remember what Adam Smith had to say about the obviousness of elitist manipulation." What an insightful point! And herein lies the seed of the bears’ (as well as the Austrian School proponents’) errors: they give credence to the concept of a vague, nebulous "Invisible Hand," never once realizing that the Invisible Hand is actually the behind-the-scenes influence of the money controllers! In today’s world that would be mostly the central bank cartels, including the Fed. The bears have this mistaken notion that the Fed doesn’t ultimately control the course of the U.S. economy and that eventually the economy will get beyond the Fed’s control. But they have again failed to consider the Golden Rule of finance: "He who has the gold makes the rule!" The interests that control the issuance of money can and do control the financial system and economic superstructure in which the money circulates. A recession/depression cannot happen unless the Fed creates it by restricting the money supply. Conversely, a financial boom cannot get underway unless directed by the Fed. This is not a statement of approval of the Fed’s operations but merely an observation of fact -- a simple yet often overlooked fact. It’s the cornerstone axiom of the GEO. That leads us to an inescapable conclusion. If in fact the Fed dictates the state of the economy, why would they create the conditions necessary for a recession/depression at this point in time? Clearly, they haven’t yet succeeded in the primary goal of a fully integrated GEO. So why botch the operation, the product of many decades of careful labor, now? Why crash the stock and real estate markets now when they are needed most to keep things flowing along at an even keel before the introduction of GEO? In my opinion, the bears need to be asking these questions among themselves. Believe it or not, there was actually a time when the Elites had planned to crash the U.S. economy and engineer a worldwide depression. The Great Depression of the early 1930s was a trial run of sorts in this direction. The financial controllers had assumed that Americans would turn to the government and cry out for help, desperate to the point of surrendering their Constitutional rights and allowing the Elites to bring about the plan for an integrated world economy through necessity. The Clinton years, however, opened their eyes and made them see that a different approach was needed. During this time of widespread (if artificial) prosperity, the Elitists observed what happened when Americans were given whatever their hearts desired. While rich in material possessions during the boom years of the late ‘90s, Americans were totally oblivious to major changes in the world economic and political scene. They were equally oblivious to the steady erosion of Constitutional liberties, federal creep, and huge tax increases that happened right under their noses during the Clinton era. As long as they were prosperous, Americans were placated and the Elitists found little resistance in proceeding with their plans of bringing about a fully functional GEO. This, they discovered, was the key to their success --engineer a bull market and keep the economy afloat as long as possible to keep everyone happy and distracted while the GEO is quietly being assembled. Thus, the bullish case won out over the bearish case. And it will most likely continue to win out for the remainder of this decade. It will become apparent to the last of the bearish hold-outs by the end of this year that their longed-for stock market crash isn’t happening as instead the markets continue to move higher. It will especially be apparent next year when there is no more pressure on top of the markets from the 10-year cycle, which even now is in the process of bottoming. The very fact that market has held up so far this year under the falling 10-year cycle is further proof that the market is being supported by the manipulators. The market has a tendency to decline beneath its falling 120-day moving average in X4 years when the 10-year cycle bottoms. This has so far been the case this year. But once the Dow breaks out above the 120-day moving average (currently at 10,200) it will rally in a big way and will astonish the bears who were fully expecting a summer crash. The bears will be further surprised when the fourth quarter witnesses further gains as well as improvement in the general economy. Another big surprise for the bears will be when oil prices continue lower in coming months, as the oil price has already peaked (as predicted in my August 11 commentary, "Is Oil Running Out of Gas?"). This has been another of they lynchpin arguments for a major global recession/depression. They never tire of talking of "Peak Oil." (If by "peak" oil they mean the oil price uptrend has peaked, then I fully agree!) Unfortunately for them, the bears have been the victims of a skillful propaganda campaign by some behind-the-scenes interest (probably short sellers who wanted to increase the downside potential in oil by getting everyone to expect a sustained long-term uptrend in the oil price). There is no "Peak Oil"! The world is positively swimming in the stuff, as perpetual oil wells have been discovered in Mexico. There are also numerous capped and untapped oil and gas wells throughout North America and elsewhere. The recent high oil and gas prices were partly a function of temporary supply disruptions (along with a high degree of market manipulation) stemming from the late war in Iraq. But aside from these temporary supply disruptions that occur from time to time, here is one reason why natural resource prices in general will remain at reasonable levels in coming years: the Elites will continue to steal resources from Third World countries, thus keeping supplies high and prices relatively low. China, the world’s up-and-coming Super Economy, has been another major concern this year. We never cease to hear in the financial press how that China is about to slip head-long into major recession or depression and that its stock market is doomed to crash. Here again the bearish case is wrong. China has bottomed. This is a simple fact that will be proven correct in coming months, although many haven’t recognized it yet. The Elites will not allow China to break down after spending the better part of 30 years of building up to the level it has reached today. GEO depends in large measure on China. Anyone who thinks the Elites will allow China to sink now needs a reality check! These are just some of the axioms of the Global Economic Order. The clear and stated goal of the ruling Elites is a fully functional, totally integrated world economy. And until they get it, they won’t allow the U.S. to sink into the financial bottomless pit. The engineered bull market recovery will continue into the foreseeable future. --------------------------------------------------------------------------- Clif Droke is the editor of the 3-times weekly Momentum Strategies Report, a forecast of U.S. equities and markets. He is also the author of more than 20 financial books, including the top-selling "Moving Averages Simplified." For free samples of his work, visit www.clifdroke.com. September 1 2004 © 1995-2004 © Gold Seek LLC Forwarded by Ron Bradley |

Left unaddressed, this bad call makes it easy to dismiss the balance of the Minority Report as similarly flawed or at best irrelevant. Moreover, it implicitly impeaches the credibility of all sound money advocates even today. After all, why should anyone pay attention to a bunch of Chicken Littles who’ve been demonstrably wrong for a generation? So it behooves us to address this question, and examine why we didn’t slip into terminal monetary crisis, as predicted, back in the 1980’s.

Our inquiry will take us through

jargon-infested waters, so we will take pains to define

our terms. We write as gold bugs, but we will also be

guided by the teachings of the great Austrian economists,

principally Ludwig von Mises and Murray N. Rothbard.

Anatomy of a Hoax For the naïve mind there

is something miraculous in the issuance of fiat money. A

magic word spoken by the government creates out of

nothing a thing which can be exchanged against any

merchandise a man would like to get. How pale is the art

of sorcerers, witches, and conjurors when compared with

that of the government’s Treasury Department![2]

To understand how our monetary system was rescued, we first need to get clear on what that system is.[3] This is not as easy as it should be. That’s because in substance it’s just a government printing press, of the type reflected in the foregoing quote from Mises. But in form it’s a holdover from an earlier time when we had a “fractional reserve” banking system with gold as the reserve asset. The structure and terminology of our current system only make sense in their original context, where, for all the many problems associated with fractional reserve banking, there was at least something real at the heart of it. Given the disconnect between form and substance in our current system, the enormous confusion that now attends the subject, even on the part of knowledgeable people, is perfectly understandable. But it makes a brief review of Fed 101 essential to making sense of what happened in the 1980’s.

The creation of our fiat money, that is, money issued by decree, or “fiat”, occurs in two phases. Phase I is controlled by the Fed, which does two things. First, it sets the level of non interest-bearing “reserves” that banks are required to hold, expressed as a percentage of their checking deposit base. That percentage is known as the “reserve ratio”. Adjusting this ratio up or down has a massive contractionary or expansionary impact on the money supply, given the multiplier effect described below, and for that reason it has been left alone for years at a marginal rate of 10%. Banks must maintain these reserves either in the form of Federal Reserve Notes kept on hand (“vault cash”), or in the form of balances held in an account at a Federal Reserve Bank (“reserve balances”).

Second, the Fed creates the reserves, and injects them into the banking system. This is where the gulf between form and substance is most telling, causing reasonable people to marvel at the brazenness of it all. The Fed creates reserves out of thin air, in the form of fresh paper notes (“Federal Reserve Notes” or “dollars”) that it prints up, or in the form of checks written on itself. It can inject reserves into the banking system in two ways. One way is to lend them to specific banks, at a rate of interest known as the “discount rate.” Reserves borrowed in this fashion are called, logically enough, “borrowed reserves.” This used to be an important tool of monetary policy, but is rarely used today.

The other way is to buy things, and pay for them with cash or credit. This is the primary tool today. Whatever the Fed buys, or “monetizes”, goes on its balance sheet as an asset. Whatever it spends, goes on the Fed’s balance sheet as a liability, but becomes a reserve asset on the books of the vendor, or on the books of the vendor’s bank, if the vendor itself is not a bank. These transactions occur either through outright purchases and sales, which have a relatively long-term impact on the level of reserves in the system, or, more commonly, through temporary arrangements known as repurchase agreements, most of which unwind quickly. The Fed buys things only from a select group of friendly finance contractors, now 22 in number, known collectively as “primary dealers.”[4] Some of these primary dealers are banks themselves; the rest operate through other member banks. Reserves created by means of these purchase and sale transactions are known as “non-borrowed reserves.”

Once the Fed has bought something and paid for it with “reserves” thus created out of thin air, Phase II kicks in. Phase II is controlled by the banks and the banks’ customers in what remains in form, despite the ethereal quality of it all, a fractional reserve banking system. The new reserve asset, which the vendor bank received in payment from the Fed, gives the bank the power to begin a process of creating more new money. The aggregate amount of new money that can be created is a multiple of the new reserve asset, equal to the reciprocal of the marginal reserve ratio, today, 10.

To illustrate this process, Rothbard walks us through it, step by step.[5] Say the Fed buys an asset for $10 from Big Bank One. That $10 will support another $100 of fresh money in the banking system in the form of new customer deposit accounts. But the new $100 doesn’t materialize all at once, or on the books of Big Bank One alone. Instead, it comes into being as the result of a gradual series of loan transactions that Big Bank One sets in motion. In what Rothbard calls a “ripple effect”, Big Bank One lends out a portion of the $10, namely $9, (1 minus the reserve requirement, or .9, times $10). That $9 ultimately gets deposited at Big Bank Two, which is the second stop in the series. Big Bank Two lends out .9 times the $9, or $8.10, and so forth, throughout the series. At the end of the series, the total new money thus created in the form of fresh deposit accounts is roughly equal to $100. Thus is our money borrowed into existence.

The same process works in reverse if the Fed, instead of buying something, sells it. This has the effect of draining reserves from the banking system, and will result in a similarly high powered contraction of the money supply.

The Fed buys things from, and sells things to, its primary dealers in what are known as “open market” transactions, so called because the Fed is operating outside its cloistered walls in the open market. The contact point is a trading desk set up in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, one of the 12 regional Fed branches. The Desk is daily in the market for U.S. Treasury securities, which comprises one of the deepest and most liquid markets in the world, with average daily turnover in the hundreds of billions of dollars. It does so in order to implement the monetary policy adopted by the “Fed Open Market Committee” (the “FOMC”) in its monthly meetings, now followed breathlessly, often without the slightest comprehension, by a host of commentators.

The way Open Market Operations work is at root quite simple. The Desk and the primary dealers maintain a market in reserves, the so called “Fed funds market.” To increase the supply of reserves in the banking system, the Desk will buy Treasuries from the primary dealers, on either a short or a longer term basis, thereby putting fresh cash in their pockets. If the supply of fresh reserves on offer from the Fed exceeds the system’s demand, as reflected in the primary dealers’ appetite, the price of those reserves, the so-called “Fed funds rate”, will tend to go down. Conversely, to decrease reserves in the banking system, the Desk will in effect bid for reserves by offering securities from its portfolio. This requires the buying primary dealers to cough up cash, thereby draining reserves. If the Fed’s demand for reserves from the primary dealers exceeds the supply available, the price of reserves, the Fed funds rate, will tend to go up.

Note that these simple hydraulics give the Fed only two things it can focus on in implementing monetary policy. It can focus on the quantity of reserves in the system. Or, it can focus on the price of those reserves, the Fed funds rate. That’s it. If it focuses on quantity, it will pick a level of reserves it’s happy with and stick with it, regardless of ebb and flow of demand from within the system. If it focuses on price, it will be darting in and out of the market with countless transactions at the margin designed to keep the Fed funds rate, rather than the quantity of reserves in the system, at a desired level.

As to the quantity of money out in the system, the Fed has direct control over just one thing: the “monetary base”, or “base money.” This is the sum of Federal Reserve Notes outstanding and reserve balances, that is, member bank reserve-deposits at Fed banks. The power to create base money is limited. It does not extend to the many other permutations of paper that make up the alphabet soup of the so-called monetary aggregates, the Ms we hear so much about:[6]

M1, which consists of currency, travelers checks, demand deposits and other checkable deposits;

M2, which consists of M1 plus savings deposits (including money market deposit accounts) and small denomination (under $100,000) time deposits issued by financial institutions; and shares in retail money market mutual funds (funds with initial investments under $50,000), net of retirement accounts;

M3, which consists of M2 plus

large-denomination ($100,000 or more) time deposits;

repurchase agreements issued by depository institutions;

Eurodollar deposits, specifically, dollar-denominated

deposits due to nonbank U.S. addresses held at foreign

offices of U.S. banks worldwide and all banking offices

in Canada and the United Kingdom; and institutional money

market mutual funds (funds with initial investments of

$50,000 or more); and the most recent (and arguably the

trendiest) entry,

MZM (Money, Zero Maturity), which consists of M2

minus small-denomination time deposits, plus

institutional money market funds (that is, those included

in M3 but excluded from M2).

The Fed’s control over the monetary aggregates declines as the subscript numbers get bigger. M3, for example, includes institutional money market funds with a $50,000 minimum investment. This element of “broad money” is totally outside the Fed’s purview. No reserves need be posted against any money market funds, let alone those held by big institutions. Technically, such funds should not be considered fiat “money” at all, as they are not immediately convertible into cash. Nevertheless, they are a prominent component in a monetary aggregate that is closely identified with Fed policy. Even M1, the narrowest monetary aggregate, consists principally of things not subject to the Fed’s direct control. So when you read breathless Internet commentary that claims the Fed is ramping up, or chopping, M3, you know you are in the presence of a misunderstanding.

As to the price of money

in the system, we see that the Fed can directly influence

the Fed funds rate through its open market operations.

But this is just overnight money. How does the Fed funds

rate actually influence the price of money farther out on

the yield curve? According to the Fed’s website, it

just does: it “triggers events”:

Changes in the federal funds rate trigger a chain

of events that affect other short-term interest rates,

foreign exchange rates, long-term interest rates, the

amount of money and credit, and, ultimately, a range of

economic variables, including employment, output, and

prices of goods and services.

Right. Actually, Fed economists and others have written a lot over the years analyzing the relationship among the various interest rates in terms of concepts such as the “Liquidity Effect”, the “Fisher Effect”, etc.[7] To those of the Austrian persuasion, these sorts of complex ratios and formulas are presumptively bogus. The real answer is that somebody has to buy or sell longer dated securities farther out on the curve in order to bring those other rates into line. If the market won’t do it, the Fed has to, directly or indirectly. Of late, the Asian central banks have acted as enforcers, freeing the Fed from the need to bulk up its or its agent banks’ balance sheets.[8] We will see below, in our discussion of interest rates under the Volcker Fed, how divergent even short term rates can get when neither the Fed nor its proxies perform this function.

From a technical standpoint, the

Achilles’ heel of the fiat money creation mechanism

is its dependence, in Phase II, on human action outside

the Fed’s control. This is the downside of keeping

the old pre-fiat form in place. The Fed can force

reserves into the system, because if primary dealers

don’t play they don’t stay primary dealers. And

the dealers (or their banks, as the case may be) have an

economic incentive to put reserves so injected to work,

because reserves don’t pay interest, and thus “excess

reserves”, or reserves over the minimum

required, are undesirable. But it is still the case that

once inside the system, reserves need to be needed. Banks

have to want to lend, and people have to want to borrow,

before the reserves can work their way through the system

and become money. The system is like a shark that has to

keep moving, or it dies. If the Fed sets the table and

nobody shows up, it gets a deflationary contraction that

it cannot influence, let alone control. This is what the

Fed confronted in everybody’s favorite oxymoron, the

Great Depression, when, as Rothbard put it:[9]

The Fed tried frantically to inflate after the 1929

crash, including massive open market purchases and heavy

loans to banks. These attempts succeeded in driving

interest rates down, but they foundered on the rock of

massive distrust of the banks. Furthermore, bank fears of

runs as well as bankruptcies by their borrowers led them

to pile up excess reserves in a manner not seen before or

since the 1930s.

Seventy years later, despite the massive substantive change that’s occurred since then, this remains the Fed’s nightmare scenario. The more recent experience in Japan following the collapse of its bubble is a subject of intense scrutiny and dread at today’s Fed.[10] That’s why Fed officials spend so much time giving speeches telling us they’re in charge and everything’s okay so go ahead and borrow (create) money. Please.

But speeches and spin only go so far.

How do you get people to borrow money into existence if

they don’t feel like it? The same way you get people

to take anything off your hands: you price it to sell.

Here it is helpful to consider the nebulous concept of

“real” interest rates, as opposed to

“nominal” interest rates.[11]

The theoretical concept is often roughly approximated as

a market, or nominal, rate less the expected rate of

inflation, and sometimes—after the fact—the

real rate is crudely calculated by subtracting the actual

rate of inflation from the prevailing nominal rate of

interest, or market yield. More sophisticated modelers of

expectations usually assume that expected future rates of

inflation are formed by current and/or recent past

inflation rates. There is thus no real rate of interest

to be discovered, there are merely a variety of attempts

approximately to measure it.

If the Fed wants to induce money creation in Phase II that it thinks would otherwise not occur, it can offer money at negative real rates, by setting the Fed funds rate below inflation expectations. This is in fact what it is doing now. At 1.5%, the Fed funds rate is well below inflation expectations. Consequently, people are literally being paid to create money.

But what if people get full, and

won’t borrow even if they’re paid to do so? We

quote Fed Governor Ben Bernanke, who has publicly

articulated the issue:[12]

Because central banks conventionally conduct monetary

policy by manipulating the short-term nominal interest

rate, some observers have concluded that when that key

rate stands at or near zero, the central bank has

"run out of ammunition"--that is, it no longer

has the power to expand aggregate demand and hence

economic activity. It is true that once the policy rate

has been driven down to zero, a central bank can no

longer use its traditional means of stimulating aggregate

demand and thus will be operating in less familiar

territory.

The Fed’s solution? Simple, says

Governor Bernanke. We’ll just slip into something a

little more comfortable, and let our inner self shine

through. No more reliance on pesky human action (id.):

Like gold, U.S. dollars have value only to the

extent that they are strictly limited in supply. But the

U.S. government has a technology, called a printing press

(or, today, its electronic equivalent), that allows it to

produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes at essentially

no cost. By increasing the number of U.S. dollars in

circulation, or even by credibly threatening to do so,

the U.S. government can also reduce the value of a dollar

in terms of goods and services, which is equivalent to

raising the prices in dollars of those goods and

services. We conclude that, under a paper-money system, a

determined government can always generate higher spending

and hence positive inflation.

The disconnect between form and substance in the system’s architecture is rivaled by the disconnect between means and ends in the Fed’s mission.

With only the crude hydraulics of a fractional reserve system ostensibly at its command, the Fed is charged, not with maintaining a stable monetary unit, a defensible goal for a central bank that would be difficult enough (indeed, historically unprecedented) for a fiat currency, but rather with achieving “maximum employment, sustainable economic growth, and price stability.”[13] Its mission is thus preposterous. But instead of owning up to the limitations inherent in the Fed’s architecture, its officials always play along, pretending to be all knowing and all powerful. This puts them under rather severe pressure, and inevitably leads, we submit, to cheating – undisclosed market intervention in furtherance of otherwise unattainable policy objectives. But we get ahead of ourselves.

So now, having completed

our little refresher course in fiat money, we can turn to

consider what happened to save the system in the early

1980’s.

That Eighties Show

Looking back at the monetary world of

1980 is rather like viewing a Currier & Ives print.

It was a simpler time. The ongoing experiment in fiat

money and “managed currencies” was only nine

years old. The global monetary system was limited in

geographic scope: the Soviet empire was still a closed

system cut off from the West, and China had not yet begun

to recover from its destructive internal upheavals. A

plausible contender for the role of competing reserve

currency was scarcely a gleam in daddy’s eye.

The U.S. domestic financial system was itself a relic of

the Bretton Woods era. Commercial banks, still separated

from investment banks and still performing traditional

banking functions like lending and intermediation of

private savings, were the principal financial

institutions. The Government Sponsored Entities that

today function as sectoral central banks, Fannie Mae and

Freddy Mac, were mere striplings. Fannie Mae’s first

purchase of a mortgage-backed security was still a year

away. The system was tightly regulated: interest rates

paid by financial institutions were capped, and only

certain financial institutions were permitted to pay

interest at all.

Financial technology was primitive. Spreadsheets were still done by hand inside the Wall Street banks, and Vydec still vied with Wang in the steno pools in the major law firms. Andy Krieger, the young derivatives trader dubbed “Patient Zero” who in 1987 would single-handedly short “the entire money supply of New Zealand,” was still studying South Asian philosophy.[14] Global OTC derivatives, had they been tracked back then by the Bank for International Settlements, would have had an aggregate notional amount of near zero.

The United States was a creditor, not a debtor. The world’s largest, in fact. The term “carry trade” had not been invented, and the Fed would not succeed in turning the United States into “The Greenspan Nation”[15] and the world into a “gigantic hedge fund”[16] for another 24 years.

But for all its quaintness in

today’s terms, the monetary world of 1980 was in

grave danger.

The Second Stage of Inflation

Inflation, wrote Mises early in his

career, is a monetary expansion that results in a decline

in the exchange value of money:[17]

In theoretical investigation there is only one meaning

that can rationally be attached to the expression

inflation: an increase in the quantity of money (in the

broadest sense of the term, so as to include fiduciary

media as well), that is not offset by a corresponding

increase in the need for money (again in the broader

sense of the term), so that a fall in the objective

exchange value of money must occur.

Later, writing at the height of the

German inflation, Mises described how inflationary

psychology creates a decreased demand for money. This

decreased demand is reflected in higher turnover of

money, as people hasten to get out of cash and into

something else. This is probably the closest he ever came

to embracing a concept of velocity:[18]

…as the monetary depreciation progresses, it is

evident that the demand for money, that is for the

monetary units already in existence, begins to decline.

If the loss a person suffers becomes greater the longer

he holds on to money, he will try to keep his cash

holding as low as possible. The desire of every

individual for cash no longer remains as strong as it was

before the start of the inflation, even if his situation

may not have otherwise changed. As a result, the demand

for money throughout the entire economy, which can be

nothing more than the sum of the demands for money on the

part of all individuals in the economy, goes down.

And some thirty years after that, he

described the three main stages of inflation in a homely

metaphor:[19]

Inflation works as long as the housewife thinks: “I

need a new frying pan badly. But prices are too high

today; I shall wait until they drop again.” It comes

to an abrupt end when people discover that the inflation

will continue, that it causes the rise in prices, and

that therefore prices will skyrocket infinitely. The

critical stage begins when the housewife thinks: “I

don’t need a new frying pan today; I may need one in

a year or two. But I’ll buy it today because it will

be much more expensive later.” Then the catastrophic

end of the inflation is close. In its last stage the

housewife thinks: “I don’t need another table;

I shall never need one. But it’s wiser to buy a

table than keep these scraps of paper that the government

calls money, one minute longer.”

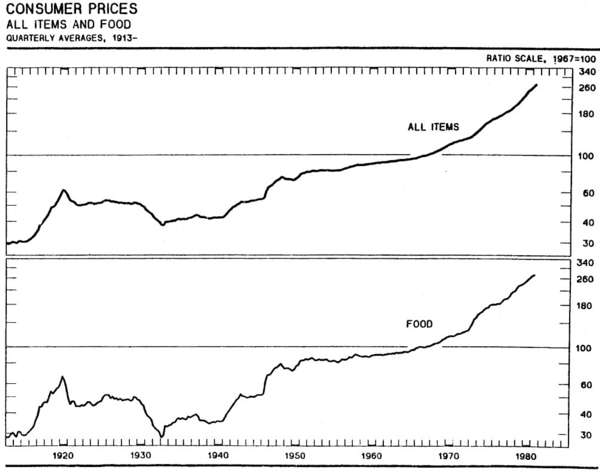

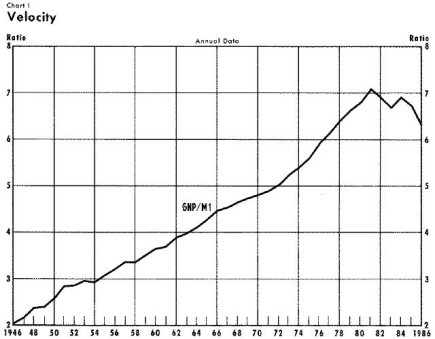

By the end of the 1970’s, we had reached stage two. The Appendix to the Minority Report contains a number of charts and tables that graphically depict the gravity of the situation as seen by contemporary observers. We reproduce a few below for ease of reference.

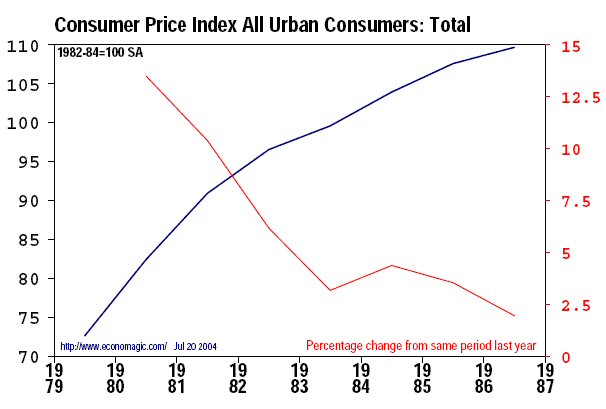

The Consumer Price Index had reached worrying levels.

Source: Minority Report Appendix, Chart 3

Today, the CPI has lost credibility among

knowledgeable observers due to results-oriented

adjustments of its components in defiance of the reality

of everyday experience.[20] At the time of the Gold Commission, however,

such measures had not yet fallen into disrepute. Even

Austrian economists conceded that for all their inherent

flaws, price indexes contributed to inflationary

psychology:[21]

The index-numbering method is a very crude and imperfect

means of “measuring” changes occurring in the

monetary unit’s purchasing power. As there are in

the field of social affairs no constant relations between

magnitudes, no measurement is possible and economics can

never become quantitative. But the index-number method,

notwithstanding its inadequacy, plays an important role

in the process which in the course of an inflationary

movement makes the people inflation-conscious.

People were indeed becoming inflation-conscious. Contracts routinely contained inflation adjustment clauses, and housewives were beginning to buy that frying pan sooner rather than later.

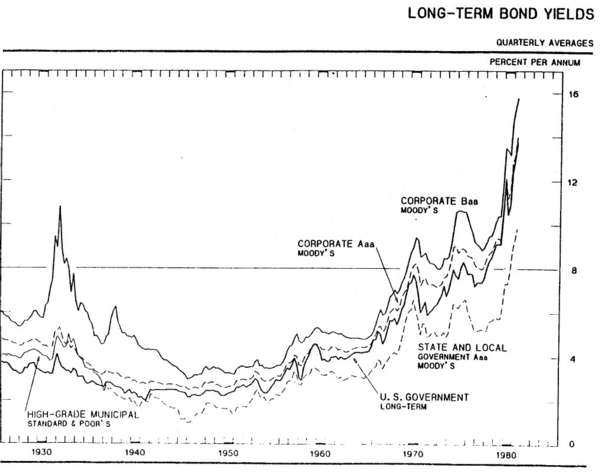

The bounty needed to induce people to hold dollar-denominated assets was skyrocketing, at both ends of the yield curve. Long term nominal interest rates were stratospheric, reflecting utter destruction in the bond market.

Source: Minority Report Appendix, Chart 9

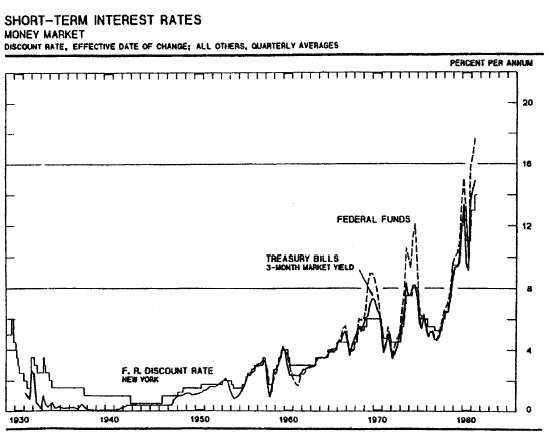

Short term rates were climbing too.

Source: Minority Report Appendix, Chart 5

It did not help matters that real interest rates, given the high price inflation, were actually low or negative for much of the 1970’s. Rates were still shocking, and the high rates were emblematic of systemic distress.

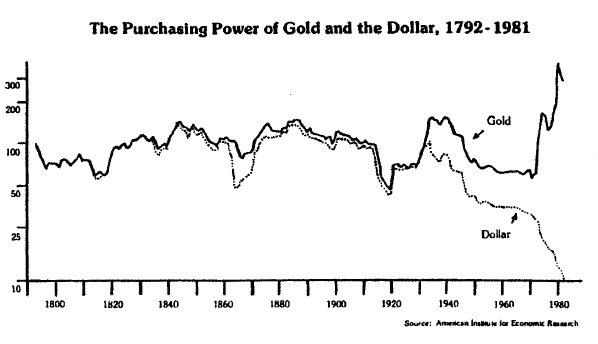

Ominously, the fiat monetary system had already lost several pitched battles in its war with gold. Lacking today’s price management technology, the U.S. and European monetary authorities had been forced to attempt to quell the gold price by means of open sales of physical metal throughout the preceding 18 years. The London Gold Pool of the 1960’s had broken down in abject failure in March 1968, leading to the abrogation of the Bretton Woods gold exchange monetary system three years later. The U.S. Treasury gold sales of the 1970’s ended in 1979, and the last of the parallel sales by the International Monetary Fund occurred on May 7, 1980.

Like interest rates, and despite the

best efforts of the monetary authorities, the gold price

was soaring, hitting $850 in the afternoon London fix on

January 15, 1980. The false premise at the core of the

fiat monetary system, the conceit that paper printed by a

government bureau is money and that gold is not, was

being exposed for all to see.

Source: Minority Report Appendix, Chart 1

Public confidence, the essential support

for fiat money, was at risk. The memory of gold as money

had not yet been fully extinguished, as reflected in the

very fact that shortly thereafter a Congressional

Commission was established to study the issue. Moreover,

the next President of the United States, who had

popularized the term “misery index” during the

election campaign, was himself a closet gold bug:[22]

Like the supply siders in congress, Reagan privately

advocated restoration of the gold standard as the

ultimate way of guaranteeing stable money. “You

can’t control inflation as long as you have fiat

money,” he told his aides. The President’s

attachment to gold was almost never mentioned in public,

however. His political advisers feared that it would

sound “kooky” and “old-fashioned” to

voters.

The very structure of the system was eroding. Membership in the Federal Reserve System was at that time elective for banks operating under state, rather than federal charters. Fed membership was expensive: member banks had to comply with the reserve ratio, and tie up funds in reserve assets that paid no interest. So new banks were being formed under state statutes, and existing members were quitting the Federal Reserve System altogether, switching their charters from federal to state and opting out of the Fed’s burdensome regulatory scheme.[23] The power of the central bank, the linchpin of the fiat monetary system, was waning.

Something had to be done. There was still time to avert a stage three inflation, but there was no time to lose.

The Making of a Legend:

Volcker the Monetarist

On August 6, 1979, Paul Adolph Volcker, a

tall, cigar-smoking ascetic, had become Chairman of the

Fed, replacing mid-term the hapless G. William Miller. In

Volcker, one of its original architects, the fiat

monetary system had finally found the perfect champion:[24]

Volcker was a public servant who had served the

government in both capitals, Washington and Wall Street.

He was a policy maker under four Republican and

Democratic Presidents and had spent years on Capitol Hill

fencing with congressional committees and lobbying for

votes. He was in Treasury when John F. Kennedy proposed

the stimulative tax cuts of the early 1960s and when

Lyndon Johnson launched the U.S. war in Indochina. Under

Nixon, he worked closely with Treasury Secretary John

Connally, an urbane Texas politician who frequently

complained about Volcker’s dowdy appearance.

(Connally once threatened to fire him if Volcker did not

get a haircut and buy a new suit.) / Together, Connally

and Volcker engineered the most fundamental change in the

world’s monetary system since World War II –

the dismantling of the Bretton Woods agreement that had

made the U.S. dollar the stable bench mark for all

currencies.

Actually, the foregoing passage likely

understates Volcker’s role in killing Bretton Woods,

as his boss, the only U.S. Treasury Secretary ever to

declare personal bankruptcy, was not noted for his

mastery of monetary arcana.

According to legend, once installed as

Chairman, Volcker quickly sized up the situation and

reoriented monetary policy to focus on the quantity

of money, rather than its price. This

famous policy shift was announced to the world in the

October 6 Record of Policy Actions of the FOMC, which

heralded:[25]

...a shift in the conduct of open market operations to an

approach placing emphasis on supplying the volume of bank

reserves estimated to be consistent with the desired

rates of growth in monetary aggregates, while permitting

much greater fluctuations in the federal funds rate than

before.

As the Fed’s primer puts it:[26]

The reserve targeting procedure from 1979 to 1982

gradually came to provide assurance to financial markets

and the public at large that the Federal Reserve would

not underwrite a continuation of high and accelerating

inflation. Reinforcing this procedure’s built-in

effects on money market conditions were judgmental

changes in nonborrowed reserve objectives and in the

discount rate. Monetary policy contributed importantly to

lowering the inflation rate sharply, albeit not without a

significant increase in interest rate volatility and a

period of marked decline in output.

It is easy to see why it is in the

interest of the Fed to embrace the Volcker legend. For

its moral is that the all-knowing, all-seeing Fed,

reluctantly but sternly facing down a crisis, did what it

had to do to kill inflation. It had the power, it had the

knowledge, and, with the right person in charge, it had

the will. If things ever get out of hand again – not

that they’d ever tolerate that, mind you –

they’d do the same thing, and whip inflation’s

sorry backside once more.

Volcker’s monetary policy was dubbed

“monetarism” by a media unschooled in monetary

theory. True monetarists, like Keynsians, accept the

legitimacy of a fiat monetary system. But unlike

Keynsians, they believe there must be a strict,

rule-based method of gradually and consistently

increasing the money supply, in contradistinction to the

herky-jerky instincts of the modern Fed. The Gold

Commission contained a number of monetarists, and their

influence is evident in the Majority Report. But the

Fed’s monetary statistics plainly show that while

Chairman Volcker was no doubt many things, a monetarist

he was not.

The Quantity of Money under the Volcker Fed

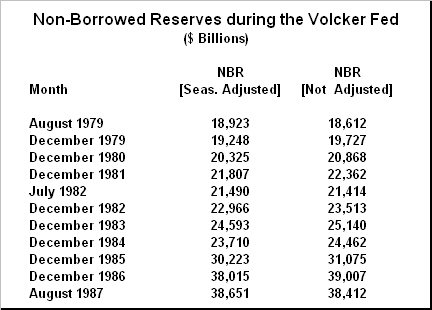

Consistent with legend, the Volcker Fed

during its so-called monetarist period was indeed rather

stingy with the supply of non-borrowed reserves to the

system.

Source: Federal Reserve

It should be noted, however, that even

during its stingy phase, the Volcker Fed made sure to

enhance the system’s back door access to borrowed

reserves, just in case. It did this by means of discount

rates that were generally set at significantly lower

levels than Fed funds rates. See table entitled “Key

Interest Rates during the Volcker Fed” in the

following section.

In any event, the stinginess was short-lived. Things

changed dramatically in July 1982. From that point on,

the Fed put the hammer to the floor and inaugurated what

would become its standard response thereafter to any

perceived systemic threat: extremely aggressive monetary

expansion. The specific catalyst for this was the failure

on July 6, 1982, of a “reckless little bank in

Oklahoma” known as Penn Square.[27] Penn

Square’s paper was widely held by a number of

important money center banks whose failure in turn was

not an attractive prospect to the monetary authorities. A

more general catalyst was the imminent sovereign default

of Mexico.

Over the next five years, non-borrowed reserves

(“NBR”) expanded at a heroic rate, roughly

doubling the levels at the beginning of the Volcker Fed.

By way of comparison, over the eight year period

commencing August 1971, that is to say, during the

inflationary hurricane preceding Volcker, Seasonally

Adjusted NBR only increased from 14,380 to 18,923, and

Not Seasonally Adjusted NBR only increased from 14,094 to

18,612. By way of further comparison, over the eight year

period commencing August 1987, that is to say, during the

warmup phase of the Greenspan Fed, Seasonally Adjusted

NBR only increased from 38,651 to 57,326, and Not

Seasonally Adjusted NBR only increased 38,412 to 56,655.

The Maestro, no slouch himself in the monetary reserve

creation department, was a piker in comparison to

post-Penn Square Volcker.

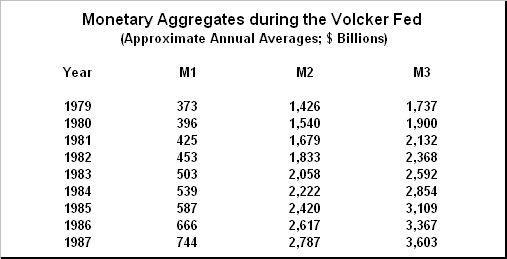

The vaunted monetary aggregates followed suit. As with

the reserve levels themselves, in the pre-Penn Square

period, the increases in the money stock, while hardly

hairshirt material, were modest in comparison to the

carnival that followed.[28]

Source: Federal Reserve

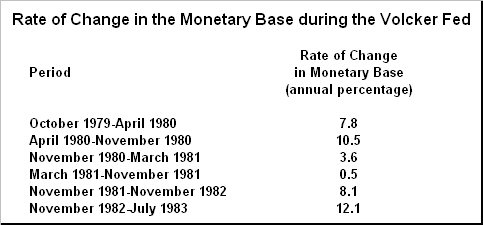

The Monetary Base under the Volcker Fed

An important plank in the monetarist critique of the

Volcker Fed is the erratic behavior of the monetary base,

the only monetary aggregate that the Fed can directly

control. The basic charge is that rather than focus on

what it could control, the Volcker Fed focused on what it

couldn’t, namely the other monetary aggregates. The

following table shows the rate of increase in the

monetary base for the periods indicated. By comparison,

the rate of change in the monetary base in the year

leading up to Volcker’s appointment was 7.2%.

Source: Monetary Trends, Federal Reserve

Bank of St. Louis, September 1983, cited in Richard

Timberlake, Monetary Policy in the United States

(University of Chicago Press, 1993), p. 359.

Indeed, Richard Timberlake marshals the foregoing data to

support his charge that Volcker’s Fed, far from

being monetarist in its policies, was just another Fed,

ramping up the money supply to aid an incumbent president

in an election year, and choking back once the results

were in.[29]

Prior to the presidential election of 1980, Fed policy

had been highly stimulative in the face of manifest

inflation. This experience, as well as the Fed’s

performance in earlier presidential elections, inspired

observers to rename the FOMC the “Committee to

Reelect the President.” The Record of Policy Actions

of the FOMC never mentioned the retention of the

incumbent president as a “goal” of policy.

Nonetheless, most of the Reserve Board members in any

given election year owed their appointments to the

incumbent and had every incentive to “play

ball.” The Fed’s performances just before,

during, and just after elections in 1960, 1964, 1968,

1972, 1976, and 1980 seemed to be clearcut examples of a

pattern that was restrictive and then stimulative during

the year before the election, and then usually

restrictive enough to slow down the inflationary reaction

after the election.

And the wide swings in the monetary base were clearly inconsistent with monetarist doctrine, which prescribed “a gentle and systematic reduction in the rate of increase in the monetary base until the growth rates of the money stocks, observed as indicators, came down to noninflationary values.”[30]

Having said that, in fairness it is not

clear that what was happening to the monetary base was

entirely within the Fed’s control. The problem is

that, as Rothbard points out,[31] the two

constituents of the monetary base, cash and reserves,

move in opposite directions. That is, cash in circulation

represents reduced reserves: once outside the banks, it

no longer counts as a reserve asset, and loses its

multiplier. If people decide to pull money out of their

bank accounts and hold it in the form of cash as opposed

to leaving it in the form of abstract deposits on the

banks’ books, this depletes reserves, turning high

powered money into chump change and initiating a rippling

contractionary process. So adjustments must be made at

the bank: aggregate deposits must shrink or reserves must

be replenished through Open Market Operations. The

contradictions inherent in our fiat money, the spawn of a

beast with the brain of a printing press and the body of

a fractional reserve banking system, are not to be

reconciled simply by focusing on the “right”

monetary aggregate.

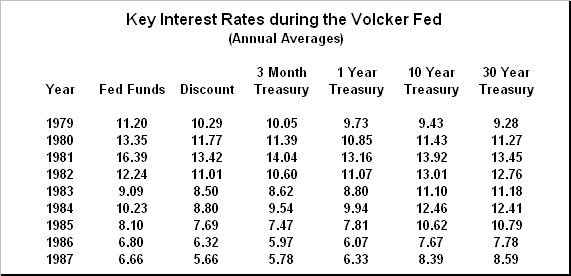

The Price of Money under the Volcker Fed

For all the talk of quantity, under the Volcker Fed

the real action was in price. The Fed essentially stood

aside and let short rates rip; the monetarist mumbo jumbo

provided intellectual cover:[32]

Throughout Volcker’s anti-inflation campaign, the

nation was instructed by the Fed to watch M-1 and the

monetary aggregates as the correct gauge of its monetary

policy. But the monetary numbers zig-zagged up and down

in a bewildering manner that confused even the

economists. The public and the politicians would have had

a far more accurate sense of what was happening if they

had ignored M-1 and simply followed interest rates and

their relative levels. Except for two brief periods in

the summer months of 1980 and the last quarter of 1981,

the Federal Reserve had succeeded in holding most

short-term interest rates above long-term rates for an

extraordinary length of time – two and one half

years. This abnormality explained things far more

reliably than what was happening to M-1 growth or the

other aggregates.

Interestingly, the average annual Fed

funds rate was actually higher than the one year Treasury

rate throughout Volcker’s tenure. Take note,

convergence theorists.

Source: Federal Reserve

The Demand for Money under the Volcker

Fed

But more important than changes in the

supply or even in the price of money under the Volcker

Fed was a pronounced increase in the demand for

money.Volcker himself, sounding like an Austrian

economist, put his finger on the demand issue in 1983:

“Individuals and businesses apparently desired to

hold more money than usual relative to incomes.”[33]

This increase in demand left tracks in

statistics generated by a mainstream mathematical formula

known as velocity. Velocity is a term used

to express the concept of turnover of units of money in

relation to broader measures of economic activity, like

GNP. As such, it is one of those equations without

meaning for Austrian economists. Indeed, Mises

specifically rejected velocity as a top-down explanatory

formula:[34]

The mathematical economists refuse to start from the

various individuals’ demand for and supply of money.

They introduce instead the spurious notion of velocity of

circulation fashioned according to the patterns of

mechanics.

Mises grudgingly acknowledged the

possibility of using velocity as a record of bottom-up

behavior, however:[35]

If there is any sense in such notions as volume of trade

and velocity of circulation, then they refer to the

resultant of the individuals' actions. It is not

permissible to resort to these notions in order to

explain the actions of the individuals.

We propose to seize that opening. The

following table shows how, after increasing steadily for

35 years, velocity of M1 suddenly fell off a cliff.

Source: Courtney C. Stone and Daniel L. Thornton, Solving

the 1980s’ Velocity Puzzle: A Progress Report

(Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, August/September

1987)

What the Fed’s chart appears to

signify is that instead of trying to get rid of their

depreciating cash, people were holding on to it. This

behavior is the exact opposite of that associated with

inflation, and the Fed’s chart, viewed merely as an

historical record, neatly captures the breaking of the

fever. It doesn’t explain why the housewife was no

longer so anxious to swap out of her cash to get that

frying pan, it just reflects the fact that this was

happening.

Back in 1914, Mises defined deflation

as the converse of inflation:[36]

Again, deflation (or restriction, or contraction)

signifies a diminution of the quantity of money (in the

broader sense) which is not offset by a corresponding

diminution of the demand for money (in the broader

sense), so that an increase in the objective exchange

value of money must occur.

This definition does not appear to

encompass a demand-driven deflation occurring within the

context of a credit expansion, that is, a situation in

which an increase in the quantity of money is

insufficient to satisfy a disproportionate increase in

the demand for money. So it is with some trepidation that

we observe that such a micro-deflation is precisely what

appears to have occurred under the Volcker Fed. The

associated decline in the rate of increase in price

levels is what mainstream economists refer to when they

use the term “disinflation.”

The resultant increase in the objective

exchange value of money found expression in a steep

decline in the rate of increase in prices tracked by the

various indexes.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

The increased demand for money was also

reflected in a marked increase in its price in real

terms. Notwithstanding the decline in nominal rates under

the Volcker Fed as shown in a previous table, real

interest rates reached levels seen only once before in

the Twentieth Century, during the Great Depression. [37]

Auf Wiedersehen, Inflation

A similar decline in velocity had marked

the monetary stabilization that followed the storied

German inflation some 60 years earlier. This was the

catastrophic, stage three inflation mentioned in the

initial excerpt from the Minority Report.

Costatino Bresciani-Turroni, a first

hand observer of the German inflation who later wrote the

definitive treatment of the subject, describes what

Austrian economists refer to as the “crack-up

boom” that was unfolding by August 1923:[38

]In the autumn of 1923 the monetary situation was as

follows: There was a great quantity of paper marks, whose

nominal value increased at a fantastic rate, but which in

reality, despite the great increase in the velocity of

the circulation, were sufficient only for a part of the

transactions in German internal business. In the total

circulation legal money now only played a secondary part,

and the need of a circulating medium was largely

satisfied by “emergency” means of payment, or

by illegal currencies.

The reduced role of the legal issue

created the necessary conditions for monetary reform, a

process that took place roughly from August through

November 1923. The reform involved the introduction of

new types of money. These were all conjuror’s

tricks, unbacked paper experiments issued in great

quantity and announced with great fanfare as “money

with a stable value.” The first of the new money

issued was in the form of “Gold Treasury Bonds”

and notes backed by a “Gold Loan”, issued

principally at the provincial and town level.

Bresciani-Turroni describes them thus:[39]

It is unnecessary to state that the guarantee of the

so-called “money with a stable value” was

purely fictitious. Actually the Gold Loan and the Gold

Treasury Bonds were mere paper without any cover. /

Indeed, the law of August 14th, 1923, on the Gold Loan of

500 million gold marks, contained only this limited

promise: “In order to guarantee the payment of

interest and the redemption of the loan of 500 million

gold marks, the Government of the Reich is authorized, if

the ordinary receipts do not provide sufficient cover, to

raise supplements to the tax on capital, in accordance

with detailed regulations to be determined later.”

These vague words constituted the entire guarantee behind

the Gold Loan! Nevertheless, the Gold Loan Bonds and the

notes issued against the Gold Loan deposits did not

depreciate in value. The public allowed itself to be

hypnotized by the word “wertbestandig”

(Stable-value) written on the new paper money. And the

public accordingly accepted and hoarded these notes (the

Gold Loan Bonds almost disappeared from circulation) even

whilst it rejected the old paper mark—preferring not

to trade rather than receive a currency in which it had

lost all faith

The most famous of these expedients was

the Rentenmark, which was authorized in October and

introduced into circulation in November 1923. Its

introduction was not accompanied by the recall of any of

the existing legal money in circulation, and its enabling

decree expressly authorized issuance in the amount of 2.4

billion, or approximately ten times the aggregate real

value of legal money then in circulation. Despite this,

and largely for psychological reasons, it was a smashing

success:[40

]In October and in the first half of November lack of

confidence in the German legal currency was such that, as

Luther wrote, “any piece of paper, however

problematical its guarantee, on which was written

‘constant value’ was accepted more willingly

than the paper mark.” If the Government had been

able to suspend the issues of paper money for the State,

probably confidence in the mark would have revived, as

had happened in the case of the Austrian crown, and as

occurred later with the Hungarian crown. But think what

would have been the psychological effect of the

Government announcing that it would issue more paper

marks to about ten times the value of the total amount of

paper circulating on November 15th, 1923! No one would

have had any faith in the promise of the Government that

later the issues would be stopped. The precipitous

depreciation of the paper mark would have continued. But

on the basis of the simple fact that the new paper money

had a different name from the old, the public thought it

was something different from the paper mark, believed in

the efficacy of the mortgage guarantee and had

confidence. The new money was accepted, despite the fact

it was an inconvertible paper currency. It was held and

not spent rapidly, as had happened in the last months

with the paper mark

Bresciani-Turroni explicitly describes the

success of the Rentenmark in terms of lower velocity:[41]

It is not difficult to explain why the monetary reform

had been accompanied not by a contraction

but by an actual increase in the quantity

of legal money in circulation. The lack of confidence in

the paper mark being lessened, consumers, producers, and

merchants ceased to be pre-occupied with the necessity of

reducing their holdings of paper marks to the minimum. In

other words, the velocity of circulation of paper

marks declined. That helped to create the need

for a new circulating medium, so that new paper marks

could be issued within the limits of this need, without