september 2004

How Israel Created The Myth of Al-Qaeda

by Seymour Hersh ©Jun 24 '04

Seymour Hersh found out that hundreds of Mossad foreign fighters have been in Iraq for a long time.

Their specialty: car bombs, sexual torture, beheadings.

These Israeli citizens came into Iraq disguised as Arab or Kurdish civilians, businessmen. Maybe "contractors"? Under contract with the Pentagon's neocon office? Your tax dollars at work?

How much of their work is blamed on Abu Musab al-Zarqawi? How much of Israel's terrorism is blamed on "Al-Qaeda"?

I have investigated the development of the "mujahideen" and here is my conclusion:

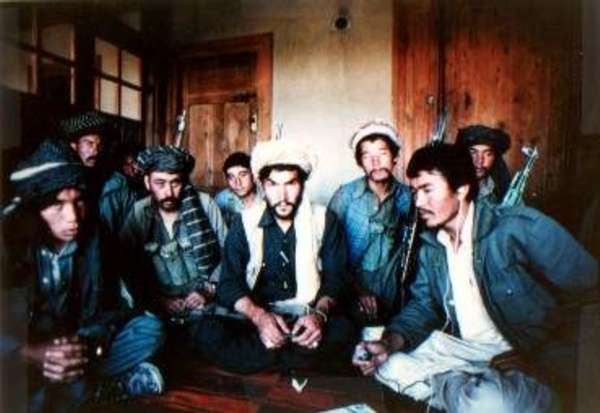

In the 80's, Israel supervised the recruitment of Arab Afghan "mujahideen" supposedly to fight against Russia. They became cannon fodder and refugees before they ended up in Guantanamo.

THEIR REAL PURPOSE WAS TO HELP ISRAEL CREATE A USEFUL MYTH: AL-QAEDA. The Arab mujahideen were rather harmless as recent revelations from Guantanamo have shown.

Israeli and Jewish-American intelligence specialists were trusted by the CIA--Israelis being "allies" and experts on the Middle East--to recruit the Arab "mujahideen" to be used by the US against Russia. Israelis disguised as Arab or Pakistani missionaries (tablighis) even ran the recruitment centers. Israelis playing Muslim missionaries (tablighis) were caught in India and Israel rushed to retrieve them.

The Arab "mujahideen" themselves were inefficient and almost useless. I have heard from the relatives of many who died in vain in clumsy incidents in Afghanistan.

All the Zionists wanted was a story, a myth that would enable them to create another myth: "Al-Qaeda." The Zionists needed this myth as an excuse for their long-term plans for the "war on terror," a war to destabilze the Middle East and pit the world against Muslims.

Neither Bin Laden nor the Arab refugees he took care of were of any military significance. The Afghans themselves were the real efficient mujahideen because they knew the territory and the tribal structure. The Afghans actually saw the Arabs as nuisance.

Arabs say "nothing comes out of a pot except what's in it." When the neocon liars speak about Arab/Islamic terrorism and Al-Qaeda, they are in fact talking about what they themselves are doing. They are talking about Israeli covert activities.

No Arabs are involved. Israeli commandos move around using forged or stolen Arab ID's and--if necessary--they wear masks to hide their real identities, such as in beheading videos.

Israelis continue to fake whatever it takes to prove that the "war on terror," i.e. the war on Arabs has to continue.

Listen to them more carefully, folks. The Zionists in our midst have been telling us the truth all along. Just replace "Arab" with "Israeli," replace "Al-Qaeda" with "Mossad," etc.

http:/= /sydney.indymedia.org/front.php3?article_id=42775

Seymour M. Hersh is one of America's premier investigative reporters. In 1969, as a freelance journalist, he wrote the first account of the My Lai massacre in South Vietnam. In the 1970s, he worked at the New York Times in Washington and New York; he has rejoined the paper twice on special assignment. He has won more than a dozen major journalism prizes, including the 1970 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting and four George Polk Awards.

He is also the author of six books, including The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Los Angeles Times BookAward, The Target Is Destroyed: What Really Happened to Flight 007 and What America Knew About It, and The Samson Option: Israels NuclearArsenal andAmericas Foreign Policy.

Published

28 November, 2003:

Does

al-Qaeda exist?

by Brendan O'Neill

www:spikedonline.com

'Al-Qaeda

bombing foiled' says the front page of today's UK Sun,

reporting the arrest yesterday of 24-year-old student

Sajid Badat in Gloucester, England, on suspicion of

involvement in terrorist activity. Other reports have

referred to Badat as 'having links with al-Qaeda' and

being a potential 'suicide bomber' (1).

Also this week, media reports claim that al-Qaeda

may have developed 'car-bomb capability' in the USA, and

that al-Qaeda has compiled a 'kidnappers' manual' and is

plotting to snatch American troops from Iraq and other

parts of the Middle East. Every day since the 9/11

attacks of 2001 there have been media reports about

al-Qaeda - its leaders, members, capabilities, bank

accounts, reach and threat. What is this al-Qaeda? Does

such a group even exist?

Some terrorism experts doubt it. Adam Dolnik and Kimberly

McCloud reckon it's time we 'defused the widespread image

of al-Qaeda as a ubiquitous, super-organised terror

network and call it as it is: a loose collection of

groups and individuals that doesn't even refer to itself

as al-Qaeda'. Dolnik and McCloud - who first started

studying terrorism at the prestigious Monterey Institute

of International Studies in California - claim it was

Western officials who imposed the name 'al-Qaeda' on to

disparate radical Islamic groups and who blew Osama bin

Laden's power and reach 'out of proportion'. Both are

concerned about the threat of terror, but argue that we

should 'debunk the myth of al-Qaeda' (2).

There is a 'rooted public perception of what

al-Qaeda is', says Dolnik, who is currently carrying out

research on the Terrorism and Political Violence

Programme at the Institute of Defence and Strategic

Studies in Singapore; but, he says, such perceptions are

far from accurate. Dolnik argues that where many imagine

that al-Qaeda is 'a super organisation of thousands of

super-trained and super-secret members who can be

activated any minute', in fact it is better understood as

something like a 'global ideology that has not only

attracted many smaller regional groups, but has also

facilitated the boom of new organisations that embrace

this sort of radical and violent thinking'. Dolnik and

others believe that, in many ways, the thing we refer to

as 'al-Qaeda' is largely a creation of Western officials.

'Bin Laden never used the term al-Qaeda prior to 9/11',

Dolnik tells me. 'Nor am I aware of the name being used

by operatives on trial. The closest they came were in

statements such as, "Yes, I am a member of what you

call al-Qaeda". The only name used by al-Qaeda

themselves was the World Islamic Front for the Struggle

Against Jews and Crusaders - but I guess that's too long

to really stick.'

So where did 'al-Qaeda' come from? Dolink says

there are a number of theories - that the term was first

used by bin Laden's spiritual mentor Abdullah Azzam, who

wrote of al Qaeda al Sulbah, meaning the 'solid base', in

1988; or that it derives from a bin Laden-sponsored

safehouse in Afghanistan in the 1980s, when he was part

of the mujahideen fighting against the Soviet invasion,

again referring to a physical 'base' rather than to a

distinct organisation. But in terms of 'al-Qaeda' then

being used to define a group of operatives around bin

Laden - that, says Dolnik, originated in the West.

Al-Qaeda was used as a 'convenient label for a group that

had no formal name'

'The US intelligence community used the term

"al-Qaeda" for the first time only after the

1998 embassy bombings', he says, when suspected bin Laden

followers detonated bombs at the American embassies in

Kenya and Tanzania, killing 224 people. Dolnik says

al-Qaeda was used as a 'convenient label for a group that

had no formal name'. Prior to the 1998 bombings, US

officials were concerned about Osama bin Laden and the

financial backing he appeared to provide to Islamic

terror groups - but they rarely, if ever, mentioned

anything called 'al-Qaeda'.

According to British journalist Jason Burke, in

his authoritative Al-Qaeda: Casting a Shadow of Terror,

'Al-Qaeda is a messy and rough designation, often applied

carelessly in the absence of a more useful term' (3).

Burke points out that while many think al-Qaeda is 'a

terrorist organisation founded more than a decade ago by

a hugely wealthy Saudi Arabian religious fanatic', in

fact the term 'al-Qaeda' has only entered political and

mainstream discussion fairly recently:

'American intelligence reports in the early 1990s talk

about "Middle Eastern extremists…working

together to further the cause of radical Islam", but

do not use the term "al-Qaeda". After the

attempted bombing of the World Trade Center in 1993, FBI

investigators were aware of bin Laden but only "as

one name among thousands". In the summer of 1995,

during the trials of Islamic terrorists who had tried to

blow up a series of targets in New York two years

earlier, "Osam ben Laden" (sic) was mentioned

by prosecutors once; "al-Qaeda" was not.'

Like Dolnik, Burke points out that the name

al-Qaeda entered the popular imagination only after US

officials used it to describe those who attacked the

embassies in Africa. 'In the immediate aftermath of the

double bombings, President Clinton merely described a

"network of radical groups affiliated with and

funded by Usama (sic) bin Laden"', writes Burke.

'Clinton talks of "the bin Laden network", not

of "al-Qaeda". In fact, it is only during the

FBI-led investigation into those bombings that the term

first starts to be used to describe a traditionally

structured terrorist organisation' (4). According to some

experts, it was this naming of al-Qaeda by US officials

that kickstarted the public's misunderstanding of Islamic

terror groups. Dolnik points out that, while US officials

talked up a structured group, this so-called al-Qaeda did

not even have 'any sort of insignia - a phenomenon quite

rare in the realm of terrorism'.

Having given bin Laden and his henchmen a name, Western

officials then proceeded to exaggerate their threat. 'In

the quest to define the enemy, the US and its allies have

helped to blow it out of proportion', wrote Dolnik and

Kimberly McCloud of the Monterey Institute in 2002. They

pointed out that after 1998, US officials began

distributing posters and matchboxes featuring bin Laden's

face and a reward for his capture around the Middle East

and Central Asia - a process that 'transformed this

little-known jihadist into a household name and, in some

places, a symbol of heroic defiance' (5).

Now, Dolnik says that Western officials have

helped to blow al-Qaeda out of proportion in other ways,

too - by 'the automatic attribution of credit to the

group for disparate attacks; by making unintelligent and

unqualified statements about the group's very basic

"weapons of mass destruction" programme; by

treating al-Qaeda as a super-organisation; by creating

the impression that al-Qaeda can do just about anything'.

As a result, al-Qaeda has been turned into something it

is not. In the mid-1990s intelligence officials saw bin

Laden as 'one name among thousands'; within a few years

they had transformed him into a global threat who heads a

ruthless, structured organisation that is capable of

doing anything, anytime, anywhere.

Anybody can make an impact by claiming a link to the

largely mythical al-Qaeda

This invention, or certainly exaggeration, of al-Qaeda is

not only inaccurate; it also has a potentially

destabilising effect, encouraging regional groups to act

in the name of al-Qaeda in the knowledge that such

actions will have a massive impact on our

al-Qaeda-obsessed world. The talking up of al-Qaeda has

created a kind of brand name, which can be invoked by

small, isolated groups wishing to strike a blow beyond

their means.

Consider the recent suicide bombings in Istanbul.

Predictably, many in the West instantly attributed the

attacks to al-Qaeda, though it has since emerged that the

bombs were most likely made and detonated by local

Turkish groups. However, at least three Turkish groups

have claimed responsibility for the attacks in the name

of al-Qaeda. The West's obsession with al-Qaeda has given

terrorist outfits a convenient shortcut to grabbing the

world's attention and scaring us senseless.

According to Dolnik: 'In a world where one email sent to

a news agency translates into a headline stating that

al-Qaeda was behind even the blackouts in Italy and the

USA, anyone can claim to be al-Qaeda - not only groups

but also individuals'.

Sajid Badat, the 24-year-old student arrested by

British police in Gloucester yesterday, on suspicion of

planning to carry out a terrorist attack, was immediately

referred to in media reports as a 'suicide bomber' and

'al-Qaeda terrorist' - after it was revealed that he had

boasted to college mates and neighbours: 'I'm in

al-Qaeda.' Whatever the truth of the allegations against

him, however, it is clear that anybody can make an impact

today by claiming a link to the largely mythical

al-Qaeda. The script for such claims has already been

written, by fearful Western officials who have made

'al-Qaeda', whatever that might be, into an instantly

recognisable, frightening, global phenomenon.

How can we challenge the widespread but warped

understanding of what 'al-Qaeda' is? Dolnik worries that

it might be 'too late', but he has some ideas: 'We could

have a balanced assessment of the group's capabilities,

including its embarrassing failures - some al-Qaeda plots

were flat-out ridiculous. We could emphasise al-Qaeda's

heretical nature within Islam, in order to decrease the

overt support for the group among fellow Muslims who are

forced to align "with us or against us". We

could stop calling everything al-Qaeda does

"new" or "unprecedented" - I am aware

of at least 10 concrete plans to use aeroplanes to crash

them into buildings and one actual successful attempt as

far back as 1976. And we could stop calling small amounts

of recovered chemicals "chemical weapons" -

without effective weaponisation, these are about as

dangerous as bullets without a gun.'

(1) Al-Qaeda bombing foiled, Sun, 28 November 2003

(2) See Debunk the myth of al-Qaeda, Adam Dolnik and

Kimberly A McCloud, Christian Science Monitor, 23 May

2002

(3) Al-Qaeda: Casting a Shadow of Terror, Jason Burke, IB

Tauris, 2003

(4) Al-Qaeda: Casting a Shadow of Terror, Jason Burke, IB

Tauris, 2003

(5) See Debunk the myth of al-Qaeda, Adam Dolnik and

Kimberly A McCloud, Christian Science Monitor, 23 May

2002 Forwarded by John Richardson

| article#42775 |