september 2004

| In 2003 global military

spending touched an all-time high of over 956

billion dollars, while the United Nations

estimates that just 11 billion dollars are

necessary to provide water and sanitation for the

people in developing countries, annually. |

- Stan Goff:

water.

Imperialism needs its stories, its pseudo-realities and pseudo-events, but it also needs its material. If the industrial-capitalist world-system needs oil as the basis of its continued capital accumulation, the human beings who inhabit and form part of this system need water.

Oil, water, food. These are

tied together more tightly than the Gordian knot. And the

pressure of their convergence is highest where the

resources are most scarce, or most hotly contested, or

both: behold the Holy Land.

Instead of beginning an examination of Palestine and

Israel with a study of religion and ethnicity (let's not

forget that 40% of Palestinians are Christian), we should

begin by looking at water.

It's hard not to take for granted what we have abusively wasted for so long. But it turns out that, despite the cherished illusions of the west, there is no cosmic faucet from which potable fresh water springs eternal. We'll figure that out soon enough, because it's becoming uncomfortably obvious as geopolitics and climate change combine to make us even thirstier than our 40,000 square miles of suburban lawns.1

Peter Grimes of Johns Hopkins University writes about water globally:

A closely related problem emerging in recent years has been a growing shortage of fresh water. The aspect of the global water cycle of concern here is the rate of flow. Fresh water on land is renewed by ocean evaporation (and desalinization) followed by rain over land, after which it eventually returns to the sea. Over geological time, fresh water has accumulated in glacial snow packs and underground aquifers. [my emphasis] (A huge example of the latter is the "Oglala Aquifer"--named after the Sioux tribe-which stretches from the Dakotas south as far as Kansas and Colorado.) The demand for fresh water for both irrigation (currently 70% of global demand and urbanization has come to exceed the flow provided by rain, most severely in drought-prone areas. To compensate, deeper wells have tapped aquifers. The Oglala Aquifer has been tapped to supply Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and farms in southern California to augment the flow of the Colorado River (itself so drained that during some summers it no longer makes it to the ocean).

In the Middle East, water access is an important obstacle to peace talks, and rationing is in effect along the Gaza strip.

- *

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

World Urged to Use Water Resources Sustainably

Emmanuel Koro©12/08/2004

The four-day International Conference on Water Resources of Arid and Semi-Arid Regions of Africa (WRASRA) that was held in Gaborone, Botswana from 3-6 August 2004, ended with delegates from all over the world calling for a “new international cooperation to use water resources to the best international advantage”.

Conference delegates noted that water scarcity was the underlying factor behind water resource problems within a society or between nations. Water resource scarcity “can lead to changes in access rights, changes in property rights, changes in property relations, greater conflicts, livelihood changes, loss and disposal of other assets, over-exploitation and competition for resources”.

Delegates attending the conference also noted that scarcity of water “often leads to its non-sustainable use”.

Over 60 papers addressing global water management issues were presented at the conference.

Presenting a key paper on the sustainable management of water in arid and semi-arid environments, scientists from the Institute for Hydromechanics and Water Resources Management at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland said, “Globally, the most widely spread forms of non-sustainable water use practices are over-pumping of aquifers, drying-up of wetlands and soil salination on irrigated land.”

The scientists said sustainable management of scarce water resources could only be achieved in the long term, “through much more careful management of scarce resources”.

Participants to the conference said that modeling was a valuable tool in the analysis of management options and scenarios. New types of data from remote sensing, airborne geophysics, and environmental tracers are among the few modern methods that “allow reaching a new quality” of prediction.

Freshwater – A Scarce Resource

Freshwater is a scarce resource on a worldwide basis. This becomes apparent by looking at the global freshwater balance. Of the 110,000 km3/area of precipitation on the landmass of the earth, 50,000 km3/area are returned to the atmosphere via evapotranspiration by the planet’s natural plant cover. Another 21,000 km3/area are used by man-made ecosystems (18,000 km3/a by rain-fed agriculture and 3,000 km3/a by irrigated agriculture). This shows that agriculture and natural vegetation are already fierce competitors for the available freshwater.

Scientists said that of the 13,000 km3/a accessible runoff, about 4,000 km3/a are used by mankind and 70 percent of this goes into irrigated agriculture.

“This means that a global water crisis would above all be a global crisis in food production,” said the scientists from the Institute for Hydromechanics and Water Resources Management at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. “Compared to the 13,000 km3/a available [as accessible runoff], the abstracted 4,000 km3/a appear small. One should, however, not forget that these figures are averaged in time and space and therefore hide the real problem; for example, droughts and floods.”

The scientists said that though most severe in arid regions, “water scarcity is on a global level”.

Sustainable Water Management

Scientists and representatives from water management authorities attending the conference said that sustainable water management “is a practice, which avoids irreversible or quasi-irreversible damage to the resource water and other natural resources linked to it, such as soil and ecosystems”.

Water scarcity and poverty are often the causes of non-sustainable behavior as they lead to overexploitation and depletion of stocks.

Global Sustainability in the Water Sector

Delegates attending the conference agreed that in order to identify big and possibly existential problems for whole regions, “we have to look for ubiquitous negative global trends”.

They identified the following as some of the non-sustainable practices, which are of global importance: over-pumping of aquifers, destruction of wetlands, salination of soils, and the pollution of aquifers with persistent pollutants.

Globally, about 800 km3/a of freshwater are abstracted from aquifers. About one quarter of this abstraction is non-sustainable in the sense that it is not replaced by recharge. On the Arabian Peninsula, in North Africa, China and the arid Western United States for example, abstractions for large-scale irrigation have withdrawn large quantities of fossil water, which under present climatic conditions are no longer replenished.

Meanwhile, the conference released information showing that the global area of wetlands has diminished by 50 percent since the year 1900. This has a dramatic impact on species diversity. It is a consequence of the competition between natural and man-made ecosystems for land and water resources.

Millions of People’s Lives Compromised

With over 160 million people living and farming in arid and semi-arid areas of Africa, delegates attending the conference warned that failure to manage water sustainably would compromise on human and environmental well being.

The delegates noted that while science could give some decisions in support of sustainable water management, “the decisions for or against sustainability are made in the political arena”.

Presenting a paper on “Challenges for Managing Water Resources in Semi-Arid Areas”, scientists from the University of Zimbabwe’s Department of Soil and Agricultural Science, and Midlands State University’s Department of Soil Science and Agriculture said, “Arid and semi-arid areas receive below 600mm of annual rainfall and together with increasing population and lack of infrastructure, this means that many people have inadequate access to water. Water scarcity and irregularity in rainfall are increasing due to the effects of EL Niño and possibly to the impacts of global warming.”

The scientists said that the variability and unreliability of rainfall makes the sustainable development of water resources difficult, hence the need to come up with clear management strategies.

“Good management of and secure rights to water resources are crucial to livelihoods and particularly to people’s capacity to cope with variability,” said the Zimbabwean scientists. “Water also provides a means for the diversification of livelihoods. It is also important for addressing poverty and rural development since it is used for food production.”

The scientists noted that Sub-Saharan Africa was among the regions suffering from water scarcity and that climate change “is likely to increase the water stress”.

They concluded, “There is now a need to investigate more thoroughly, the links between water potential resource base and how it is managed during the season and dry years and see if there are any opportunities for reducing water scarcity.”

* Emmanuel Koro is an

environment and development communication specialist

based in Zimbabwe. He is also President of the

Sub-Saharan Africa Forum for Environment Communicators

(SAFE), which aims to promote the conservation and

development views and interests of rural communities in

the media. Your emails to will be forwarded to him by

contacting the editor at: ScienceTech@islam-online.net.

Recycled Water Turns Jordan's Deserts Green |

|||||||||||||

22/04/2004 |

|||||||||||||

"For in the waterless region, as it is called, [the Nabataeans] have dug wells at convenient intervals and have kept the knowledge of them from people of all other nations, and so they retreat in a body into this region out of danger. For since they themselves know about the places of hidden water and open them up, they have for their use drinking water in abundance." [Diodorus, II.48.2]

This 1st century BC description of the life of the Nabataeans in the Jordanian desert shows that water scarcity in this part of the world is nothing new. Already two thousand years ago survival in this harsh climate depended on the ingenuity and inventiveness of the local population. Part of the strength of the powerful Nabataean civilization that thrived from the 6th century BC to the 3rd century AD lies in their refined water management system. Walking through the extensive ruins at the historic Nabataean site of Petra today, one can still see the cisterns, wells and water channels scattered across the site. Today tourists see these Nabataean water works as mere curiosities, but many Jordanians are coming to realize that these relics of the past also hold relevant messages for the present. For just as the Nabataeans developed a refined system of collection and storage devices to make use of every drop of water, the current water crisis in Jordan means every option has to be considered Modern-Day Jordan's Water Crisis Indeed, the Desert Kingdom did not earn its name for nothing, and except for the water from the Jordan River and its tributaries – which the Hashemite Kingdom shares with Israel and Syria – the country relies entirely on scant rainfall and groundwater reserves. The effects of this natural scarcity have been compounded by a sharp increase in population figures over the last 50 years, making Jordan one of the ten poorest countries in the world in terms of water resources[1]. Water scarcity is an undeniable part of life here and everyone in Jordan feels its impact with citizens receiving just 24 hours of water a week. Agriculture, the largest consumer of water throughout the region, has also been curtailed and still, the situation is precarious: all the reserves are stretched to their limit, forcing the country to turn to alternative sources such as desalinated water and treated wastewater Treated wastewater for the irrigation of agricultural crops is being used more and more frequently, not only in Jordan but throughout the Middle East. Domestic wastewater from kitchens, gardens and bathrooms – not from toilets – is processed and recycled to make it fit for use in agricultural settings. Recycled Water Brings Prosperity to Wadi Musa

Near the ruins of Petra in southern Jordan, this new technique is now being applied to treat the wastewater from Petra’s many tourist facilities and provide water to local farmers. Thus, today Petra does not only bring an income to the tourist business, but also, indirectly, to the agricultural sector. The Wadi Musa Reuse Project – a joint initiative of the Jordanian Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation and the American donor agency USAID – produces 1.25 million cubic meters of agricultural water a year, providing freshwater for the irrigation of 1,070 dunums[2] of land. Initiated in September 2002, the scheme is already bearing its fruits: local farmers are cultivating a wide variety of crops including barley, sorghum and vegetables Her Highness Sharifa Zein Bint Nasser, the head of development for the Royal Hashemite Court and one of the project’s initiators, explains that this is the first time any such initiative has been undertaken in the Middle East. “This is a groundbreaking project: it is the first time that treated wastewater is being used by local Bedouin tribes. We very much hope that the project will serve as an example to the whole country,” she says. She explains that what makes the project at Wadi Musa unique is not so much the use of treated wastewater, but the fact that local farmers are being directly involved in its use. Near the main site there is a small demonstration area where a wide variety of plants, trees and flowers are being grown; they were all selected to resist the arid climate of Wadi Musa and are irrigated by drip irrigation, ensuring efficient water use. Bedouin Tribe Embraces Project HH Sharifa Zein says that it was partly thanks to the creation of this demonstration area that the local Bedouin tribe, the Ammariin, embraced the idea of using treated wastewater for irrigation. “In the beginning they all saw the wastewater treatment plant as an awful and ugly thing, a building that stank. And the treated wastewater that flowed from the plant through the valley was left untouched; the farmers wouldn't even let their livestock drink it… To them the water was impure and haram, and they believed that any animal that had drunk it would become impure and be unfit to sell at the market,” she says. She recalls that it took “hundreds of cups of tea and coffee and night upon night of sitting in tents and discussing the project with the community”, before the local farmers of the Ammariin tribe accepted the idea of treated wastewater. “We showed them examples in which treated wastewater had been successfully used for the irrigation of crops in Tunisia. And we were also able to show them a fatwa that had been issued by scholars at Al Azhar University in Cairo, approving the use of treated wastewater for the irrigation of crops. Once they saw the results of the demonstration site they were really convinced: now we have managed to make them see that water is valuable, that it is not just a commodity to be looked down upon and that even this treated water is a precious resource.” The land on which the treatment plant stands is today owned by the government, but in the past it belonged to the Ammariin tribe. They are therefore the main beneficiaries of the project, and the tribe has been organized in a cooperative of 200 members, with men and women partaking as equal shareholders. “The fact that women are given equal say in the day-to-day management and running of the project is another unique feature of the project,” says HH Sharifa Zein. She explains that the tribe elders were initially reluctant to allow women to participate in such a manner, but they have now also come to see the benefits. Ismail Twaissi, the agricultural engineer in charge of the project, is very pleased with the results at Wadi Musa. “We really hope to change the lives of local farmers with this project. Before they had to wait for rain, with this project they know they will have a reliable and steady supply. We can already now see the difference,” he says. Besides having to get used to the concept of treated wastewater, Twaissi explains that there were many things the farmers had to learn in the initial phases. “The farmers often don't know how to deal with the new crops they are planting,” he explains. “They don’t know when to sow them and when to harvest them; how to apply the right amounts of fertilizer. They also needed help with the use of the drip irrigation system; they had never used this before. There is a lot for them to learn.” While animal fodder is the principal crop now, Twaissi points out that a variety of trees have also been planted – both in the demonstration site and on the individual plots. Native trees such as juniper, pistachio, almond and olive have been reintroduced with the aim of restoring plant diversity in the region and combating desertification. Spin-off Projects Develop

While the project is barely a year and a half old, members of the cooperative are already so pleased with the results that they are starting to take initiatives to increase the value of the project. The farmers had the idea of selling their produce, mainly animal fodder, to farmers from other tribes. They are now planning to build a storage facility on the site and hold weekly market days to sell their crops in the area. Since the end of 2003 there is also a small greenhouse in the demonstration area, where four women tend to a variety of cut flowers. These will soon be sold to the larger hotels in Petra and Aqaba, generating an additional income for the cooperative. Hajja Amal, one of the young women working in the greenhouse, is very pleased with her new job. “Before this I never worked; with this new job I feel I am learning a lot. My work is also useful: both for the community and for my family,” she says. “Already the wastewater treatment project is generating spin-off projects. Over time all these projects will start generating their own income and become sustainable,” comments HH Sharifa Zein. But she cautions, “We have to beware that we don't spread ourselves too thinly; the projects must be built up gradually.” Nevertheless, she already has

ideas for the next project: the cultivation of

herbal plants. The valleys around Petra harbor

many rare species of medicinal plants and herbs

and HH Sharifa Zein believes that this could be

another project for local women: the development

of the herb garden which could form an additional

tourist attraction in Petra and at the same time

provide a source of income to the Ammariin

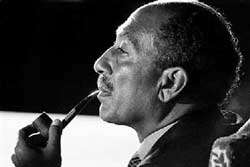

cooperative. Water Wars IslamOnline Exclusive With Boutros Ghali

Francesca De Châtel reports from Paris on her visit to the former Secretary General of the United Nations, Boutros Ghali, and his convictions about possible water wars in the 21st century. Professor Boutros Boutros Ghali, the ex-Secretary General of the United Nations, has said he still believes water scarcity could lead to war in the 21st century. He reiterated the concern he first voiced in 1985 when he said that “the next war in the Middle East will be fought over water, not politics.” He predicts that explosive population growth and the intensification of agricultural cycles throughout the Middle East and Africa will put great pressure on the already-dwindling water reserves of the region – a pressure that could result in armed conflict. Today, on the eve of the Third World Water Forum, he has again called for cooperation, not confrontation, between the countries facing the looming threat of water scarcity. The Nile Basin: A Perfect Example Taking the Nile Basin as an example of the difficulties involved in equitable water distribution, Boutros Ghali explained that current use of Nile waters is sure to increase as riparian countries develop their agriculture and their economy. Countries like Sudan and Ethiopia today still rely on rain to water their crops; once they embrace irrigated agriculture, their downstream neighbor Egypt will inevitably receive less water. If in addition population figures in the region continue to soar, he foresees serious consequences. “They will all be vying for the same water and the situation will be so dramatic that they will take to arms. Water may not be the apparent reason for the conflict, but it will certainly lie at its origins. If, for instance, 50,000 refugees cross the border from Ethiopia to Sudan because of drought and they attack a village, then Sudan will attack Ethiopia over this: ostensibly this will not be a conflict about water, but the problem of water will nevertheless lie at the root of this military intervention.” A Long History in Water Affairs

Boutros Ghali has long recognized the gravity of the water question in the Middle East. During his period as Egypt’s minister of foreign affairs from 1977 to 1991, he repeatedly witnessed that emotions can run high over the sharing of the region’s most precious resource. Thus, when President Sadat offered the waters of the Nile to Israel in a bid to opendiscussions about the West Bank and Gaza, there was public outrage in Egypt and beyond, with upstream countries protesting that the Nile waters were not President Sadat’s to distribute at will. Boutros Ghali sees this as just one example of how water can become a political issue. “It is

interesting to see how water was used as a

political tool here. Water lies at the core of

the problems in Israel. This is why [the

Israelis] are interested in the Occupied

Territories; not for the territory, but for the

water within that territory. The problem of water

will definitely have to be addressed [as part of

a peace agreement]: Palestinians only have access

to about 18 per cent of water within the Occupied

Territories. This inequality needs to be

resolved.” In 1978 tensions over water reached a new peak when President Sadat threatened Ethiopia, which controls 85 per cent of the Nile waters, with military intervention if it embarked on any development projects that might affect the flow of the Nile northwards to Egypt. The incident was not well timed for Boutros Ghali: he had been working to strengthen Egypt’s relationships with its downstream neighbors and initiate a dialogue between riparian states. “Water was my main obsession,” he remembers. “I tried to raise awareness of the importance of cooperation between riparian states over the sharing of the Nile waters; I wanted to show Egyptians that the security of Egypt is related to the south, to Sudan and Ethiopia, rather than to the east and Israel.” “Fraternity” Demands Oil for Water In this context Boutros Ghali created an organisation that brought together the ministers of irrigation of the nine riparian states: Sudan, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda and Congo. Called Undugu, which means fraternity in Swahili, the group aimed to build a comprehensive development plan in the Nile Basin. The ambitious scheme proposed by Egypt outlined the construction of a series of hydroelectric dams along the Nile, which would create a network of hydropower plants through the region. The generated electricity would then be exported to other regions in exchange for hard currency; an electricity grid that covered Uganda’s proposed Inga Dam and Egypt’s Aswan Dam would transfer power to the networks of Jordan, Syria, Turkey and beyond to the European Community. Unfortunately, lack of trust between member states and political instability in Ethiopia, Sudan and Uganda meant the project was doomed to failure. “From the beginning there was mistrust between members: upstream countries were suspicious of Egypt’s demands and wanted something in exchange for the water they would cede to Egypt. They even said that they would demand a barrel of oil for each barrel of water they gave away.” The Technical/Political See-Saw Boutros Ghali is pensive: “[It] raises the question whether the water problem can be solved on a technical level only, or whether you need a political dimension. My belief is that you need a political dimension; you cannot receive from an upstream country without offering something in exchange. “I had a discussion with the Egyptian minister of irrigation. He believed the problems should be solved on a technical level and that introducing politics only complicated things. But my theory was quite the opposite: unless there is political consensus among members, it is impossible to seek assistance from international organisations and donor countries on a technical level.” Boutros Ghali still believes that the threat of water wars in the Nile Basin can be averted through the creation of an international organisation that monitors and coordinates the distribution of water according to a set of objective criteria. Emphasising the importance of a foreign mediator, he says a higher body needs to be brought in to play a facilitating role between member states and to ensure the criteria set by the organisation are observed. “One of the problems of setting up projects in developing countries is that they are not able to embrace long-term projects; they are only interested in finding short-term solutions,” he says. He believes an international organisation could provide a solid base on which to build a sustainable and lasting collaboration project in the Nile Basin. At first sight the recently created Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) appears to satisfy these requirements. Backed by international organisations such as the World Bank and the United Nations Development Project, the NBI is endorsed by all riparian states and aims to achieve “sustainable socio-economic development through the equitable utilisation of (…) Nile Basin water resources. Poverty and ignorance complicate any kind of reform in these countries.” Yet like its predecessor Undugu, the NBI is wrestling with the long history of mistrust between the nine riparian states. Its initiatives to date have all focussed on confidence-building; working on the so-called “win-win projects” that are beneficial to all and postponing the resolution of key issues to a later date. The question is when these issues will be addressed and whether the institution will be strong enough to resolve the inevitable conflicting interests of member states. While the political dimension has to play a crucial role in the future resolution of water shortage, Boutros Ghali believes raising awareness at a community level is also important. He explains that there is no tradition of restricting water use, or of encouraging thriftiness: people don’t attach value to water because it is free. “The distribution of water in the city is very cheap, and the distribution of water on the land is gratis. The day you put a tax on water, people will behave differently.” But he admitted that addressing water scarcity was a complex challenge in the developing world. “Poverty and ignorance complicate any kind of reform in these countries,” he says. “If you tell people they should save water because there will be scarcity in 10 years, they will say to you: ‘I don’t even know how I will find food for my children tomorrow, so don’t talk to me about the problems in the next 10 years. Allah will solve the problems that lie 10 years away.” * Francesca De Châtel is a Dutch journalist and writer specializing in water issues in North Africa and the Middle East. She may be reached at: dechatel@hetnet.nl [1] Jordan has a water availability of 175 cubic meters of water per capita per year, well below the internationally recognized minimum of 1,000 cubic meters of water per capita per year. [2] 1 dunum=1,000 square meters |

|||||||||||||