AUGUST2007

History Erased

By Meron Rapoport

In July 1950, Majdal - today Ashkelon - was still a mixed

town. About 3,000 Palestinians lived there in a closed,

fenced-off ghetto, next to the recently arrived Jewish

residents. Before the 1948 war, Majdal had been a

commercial and administrative center with a population of

12,000. It also had religious importance: nearby, amid

the ruins of ancient Ashkelon, stood Mash'had Nabi

Hussein, an 11th-century structure where, according to

tradition, the head of Hussein Bin Ali, the grandson of

the Prophet Muhammad, was interred; his death in Karbala,

Iraq, marked the onset of the rift between Shi'ites and

Sunnis. Muslim pilgrims, both Shi'ite and Sunni, would

visit the site. But after July 1950, there was nothing

left for them to visit: that's when the Israel Defense

Forces blew up Mash'had Nabi Hussein.

This was not the only Muslim holy place destroyed after

Israel's War of Independence. According to a book by Dr.

Meron Benvenisti, of the 160 mosques in the Palestinian

villages incorporated into Israel under the armistice

agreements, fewer than 40 are still standing. What is

unusual about the case of Mash'had Nabi Hussein is that

the demolition is documented, and direct responsibility

was taken by none other than the GOC Southern Command at

the time, an officer named Moshe Dayan. The documentation

shows that the holy site was blown up deliberately, as

part of a broader operation that included at least two

additional mosques, one in Yavneh and the other in

Ashdod.

A member of the establishment is responsible for the

documentation: Shmuel Yeivin, then the director of the

Department of Antiquities, the forerunner of the

present-day Antiquities Authority. Yeivin, as noted by

Raz Kletter, an archaeologist who has studied the first

two decades of archaeology in Israel, was neither a

political activist nor a champion for Arab rights. As

Kletter explains, he was simply a scientist, a disciple

of the British school and a member of the Mandate

government's Department of Antiquities who believed that

ancient sites and holy places needed to be preserved,

whether they were sacred to Jews, Christians or Muslims.

In line with his convictions, he fired off letters of

protest and was considered a nudnik by the IDF.

"I received a report that not long ago, the army

blew up the big building in the ruins of Ashkelon, which

is known by the name of Maqam al-Nabi Hussein and is a

holy site for the Muslim community," Yeivin wrote on

July 24, 1950, to Lieutenant Colonel Yaakov Patt, the

head of the department for special missions in the

Defense Ministry, and sent a copy to chief of staff

Yigael Yadin and other senior officers. "That

building was still standing during my last visit to the

site, on June 10 - in other words, the army authorities

found no reason to demolish it from the conquest until

the middle of 1950. I find it hard to imagine the site

was blown up due to infiltrators, as they have not

stopped infiltrating the area during this entire

period."

The detonation, by the way, was extremely successful. Of

the ancient and holy site, not so much as a stone

remained.

Yeivin's complaint was seemingly related to procedural

matters, but only seemingly. The army, he wrote, needed

to understand that there were "sanctified

buildings," and if it wanted to touch them, "it

is proper, honest and courteous first to talk to the

institutions that supervise these areas and buildings,

and to consult with them in order to find ways to avoid

destruction." But that is not happening, Yeivin

stated. "I was told that simultaneously, the mosque

in the abandoned village of Ashdod was blown up,"

Yeivin added. "This is not the first case. I already

have had many occasions to draw your attention to similar

cases elsewhere, and the chief of staff issued explicit

directives with regard to the preservation of such

buildings and places, but apparently none of this avails

commanders of a certain type ... I believe the commander

responsible for this explosion should be brought to trial

and punished, because in this case there was no

justification for a swift, war-contingent

operation."

A perusal of the IDF Archives shows that Lieutenant

Colonel Patt forwarded Yeivin's complaint to Yadin.

However, Yadin, who would later become Israel's

preeminent archaeologist and whose father, Eliezer

Sukenik, was an archaeologist of repute in his own right

and Yeivin's colleague in the Mandate Department of

Antiquities, was not unduly upset. Below Patt's letter

addressing Yeivin's complaint are handwritten remarks:

"1. Confirm receipt of letter and inform that the

matter is being dealt with; 2. Add to Dayan's material

for my meeting with B.-G." - referring to then prime

minister and defense minister David Ben-Gurion.

It stands to reason that the handwriting is Yadin's, as

it is unlikely that anyone else could have met with

Ben-Gurion concerning "Dayan's material." And

Yadin, as is clear from another note written on the

letter, did not attribute any great importance to the

complaint. "Teven la'afarayim," it says,

roughly the equivalent of "coals to Newcastle"

- in short, there is nothing new in Yeivin's complaint.

Nor was Dayan unduly upset. In a response he sent to the

chief of staff's bureau, apparently on August 10 under

the heading "Destruction of a holy place,"

Dayan wrote: "The detonation was carried out by the

Coastal Plain District, at my instruction." The

first words of the sentence have been struck out, but a

letter dated August 30 removes all doubt. Dayan replied

to a letter concerning "damage to antiquities in the

Ashkelon area": "The chief of staff approached

me and I gave him my explanations; the action was carried

out at my instructions."

That reply was so embarrassing that Yaakov Prolov, the

head of the Operations Department in the General Staff,

sent a letter to the chief of staff's bureau asking for

guidelines on how to reply to Yeivin. "A mistake was

made here and it can be assumed it will not happen

again," someone instructed him in script that looks

like that attributed to Yadin in the previous letter.

Whitewashing, it turns out, is not a new invention.

Blots on the landscape

Not surprisingly, it did in fact happen again. At the end

of October, Yeivin sent another letter, this time

directly to Yadin, to complain about "the blowing-up

of the ancient mosque at Yavneh," a 1,000-year-old

structure whose minaret is still standing on a hill south

of Yavneh, close to the train station. Yeivin reminded

Yadin that he had been promised that those responsible

would be punished this time. But it turned out there was

an unexplained disparity between the explicit orders

prohibiting damage to mosques and the actual policy in

the field.

"I have just received an official reply from your

bureau chief [Michael Avitzur], and after reading it I am

totally at a loss," Yeivin wrote to Yadin. "On

the one hand, I have in front of me your explicit order,

which speaks unequivocally about preserving places of

archaeological or historical value ... On the other hand,

I read in the letter of Lieutenant Colonel Michael

Avitzur that the mosque at Yavneh 'was exploded on July

9, 1950, before the date on which the cessation of

blowing up mosques was announced.' How can these two

things be reconciled?"

Yeivin's quotation from Avitzur's letter makes it clear

that blowing up mosques was widespread enough that it

required a special order to stop it. Yeivin himself wrote

later in the letter, "I am extremely concerned

following my talks with a number of people involved in

the policy on this question." Yeivin did not specify

whom he spoke to, but noted, "I do not see myself as

being able to write explicitly about everything."

David Eyal (formerly Trotner), who was the military

commander of Majdal at the time, says "he does not

want to return" to that period. The historian

Mordechai Bar-On, who was Dayan's bureau chief during his

term as chief of staff and remained close to him for

years, says he himself did not serve in Southern Command

at the time and therefore is not familiar with the

destruction of mosques in Ashkelon, Yavneh and Ashdod,

and also never heard Dayan issue any such order.

"As a company commander in Central Command, we

expelled the Arabs from Zakariyya, but we did not destroy

the mosque, and it is still there," Bar-On says.

"I know that in the South, in the villages of Bureir

and Huj [near today's Kibbutz Bror Hayil], the villages

were leveled and the mosques disappeared with them, but I

am not familiar with an order to demolish only mosques.

It doesn't sound reasonable to me."

The affair of the mosque demolitions does not appear in

Kletter's book "Just Past? The Making of Israeli

Archaeology," published in Britain (Equinox

Publishing) in 2005. Kletter, who has worked for the

Antiquities Authority for the past 20 years, does not

consider himself a "new historian" and has no

accounts to settle with Zionism or the State of Israel.

Nevertheless, the story of archaeology comes across in

his book to no small degree as one of destruction: the

utter destruction of towns and villages, the destruction

of an entire culture - its present but also its past,

from 3,000-year-old Hittite reliefs to synagogues in

razed Arab quarters, from a rare Roman mausoleum (which

was damaged but spared from destruction at the last

minute) to fortresses that were blown up one after the

other. Had it not been for a few fanatics like Yeivin,

who pleaded to save these historical monuments, they

might all have been wiped off the face of the earth.

As the documents quoted in the book show, only a small

part of this devastation occurred in the heat of battle.

The vast majority took place later, because the remnants

of the Arab past were considered blots on the landscape

and evoked facts everyone wanted to forget. "The

ruins from the Arab villages and Arab neighborhoods, or

the blocs of buildings that have stood empty since 1948,

arouse harsh associations that cause considerable

political damage," wrote A. Dotan, from the

Information Department of the Foreign Ministry, in an

August 1957 letter that is quoted in Kletter's book. A

copy was sent to Yeivin in the Department of Antiquities.

"In the past nine years, many ruins have been

cleared ... However, those that remain now stand out even

more prominently in sharp contrast to the new landscape.

Accordingly, ruins that are irreparable or have no

archaeological value should be cleared away." The

letter, Dotan noted, was written "at the instruction

of the foreign minister," Golda Meir.

Kletter reveals in his book that Yeivin and his staff

occasionally tried to stop the destruction - not always,

not consistently, and not for moral reasons or out of any

special respect for the people (the Arabs) who lived for

centuries in these towns and quarters. Their grounds were

scientific, and Kletter believes this approach stemmed

from their background. Before 1948 they worked for the

Department of Antiquities of the Mandate government under

British management, alongside Arab employees. Kletter

relates that in the department they fought for the

"Judaization" of the names of ancient sites,

but nevertheless remained loyal to the department - so

much so that after the United Nations passed the

partition plan, in November 1947, Yeivin proposed that

the department remain unified even after the country's

division into a Jewish state and an Arab state. Eliezer

Sukenik went one step farther: "I do not believe the

Jewish state will preserve its antiquities," he said

in a December 1947 discussion. "We must place

scientific sovereignty above political sovereignty. We

are interested in the archaeology of the whole land, and

the only way [to ensure this] is a unified

department."

Perjury at Megiddo

"Yeivin was not the greatest archaeologist in the

world, but he had personal integrity, which is the most

important trait of the British heritage," Kletter

says. "But that heritage did not suit the

nationalism of the 1950s, because Ben-Gurion wanted to

erase everything that had been, to erase the Islamic

past."

Ben-Gurion saw everything that existed here before the

revival of the Jewish community as wasteland.

"Foreign conquerors have turned our land into a

desert," he said at a meeting of the Society for

Land of Israel Studies in 1950. Thus the failure of

Yeivin and his colleagues was a foregone conclusion. In

the 1950s, when archaeology was a fad and archaeologists

like Yadin were cultural heroes, people of science were

nudged out of management positions. Yeivin was forced to

resign and "technocrats" like Teddy Kollek were

effectively put in charge of managing Israel's major

archaeological sites.

The Department of Antiquities was formally established in

July 1948, as a unit of the Public Works Department in

the Ministry of Labor. Even before this, the veterans of

its Mandatory predecessor tried to preserve antiquities,

and in particular to prevent looting, but did not always

succeed. The museum in Caesarea was emptied out by

thieves, and the same fate befell the findings and

documents at Tel Megiddo, which were concentrated in the

offices of the University of Chicago archaeological

expedition, which had been digging there since the 1920s.

Rare collections, such as the one at Notre Dame Monastery

in Jerusalem, disappeared almost completely, and private

collections and antique shops in Jaffa and Jerusalem were

also targeted by thieves. "All the objects have

disappeared from the government museum [more than 100

fragments of inscriptions and parts of pillars],"

reported Emanuel Ben-Dor, who would later become Yeivin's

deputy director, after visiting Caesarea. "The

collection in the office of the Greek patriarch was

destroyed." The Megiddo incident was particularly

embarrassing, as the dig was carried out by American

archaeologists and the U.S. consulate wanted to know who

was responsible for the devastation. An investigation was

launched under Yeivin's supervision, and the local

commanders said that Arab units had wrecked the site.

Yeivin discovered that this was untrue, and that Israeli

soldiers had looted the site and then burned the

archaeological expedition's offices.

In a confidential report, Yeivin quoted from an internal

letter of the local unit: "In consultation with the

battalion commander and with the brigade's operations

officer, we agreed that in the event of an investigation

by the U.S. consul general ... we will (shamefully) lie

and say the place was found in this condition when it was

captured and that the crime was committed by the Arabs

before they fled."

But the theft of antiquities was only a small part of the

problem. The major problem was the destruction. In August

1948, the army started to demolish ancient Tiberias,

apparently in the wake of a local decision. The attempts

to salvage some of the town's archaeological gems were to

no avail. In September the site was visited by Jacob

Pinkerfeld, from the Department of Antiquities' monument

conservation unit.

"In ancient Tiberias the army began to blow up a

hefty strip of buildings in the Old City,"

Pinkerfeld wrote in his report. "In talks with all

the responsible parties at the site, we emphasized the

special importance of the ancient stone with the relief

of the lions on it, which was built into one of the

walls. We were promised that this antiquity dating back

3,000 years would be specially guarded, but in my last

visit I found precisely this stone blown to bits."

So sweeping was the destruction of Tiberias that even

Ben-Gurion was taken aback when he visited the city in

early 1949.

The list for destruction sometimes assumed ludicrous

proportions. During a visit to Haifa in August 1948,

Yeivin discovered the army was laying waste to large

sections of the Arab city around Hamra Square (now Paris

Square) under the direction of the city engineer. In his

restrained language, Yeivin expressed his astonishment at

the destruction: "With our own eyes we saw the ruins

of half of a building that had served as a synagogue on

the Street of the Jews ... According to Jews who live

there and wandered about among the ruins, another two or

three synagogues were also destroyed there ... It would

appear that with attentiveness, the damage inflicted to

these holy buildings could have been avoided."

Depressing impression

The leveling of the villages began as soon as the

fighting ended. During his visit to the North, Yeivin saw

the army blowing up villages near Tiberias and Mount

Tabor. He asked that before villages were demolished,

consultations be held with representatives of the

Department of Antiquities, because "in many

villages, ancient building stones are embedded in the

houses." At Zir'in (now Kibbutz Yizrael) a Crusader

tower was blown up, and the fortress at Umm Khaled, near

Netanya, was reduced to rubble.

But there were successes, too. An order was issued to

raze the fortress at Shfaram, but Antiquities Department

staff arrived at the last minute and blocked the

demolition. And at Al-Muzeirra, a village south of Rosh

Ha'ayin, a miracle occurred: the army used a handsome

building of pillars in the middle of the abandoned

village for target practice, apparently without knowing

it was "the only mausoleum that survived in our

country from the Roman period," according to Yeivin.

When, nonetheless, the decision came to blow up the

mausoleum in July 1949, an antiquities inspector arrived

at the site and prevented the blast. The site is now

known as "Hirbat Manor" (the Manor Ruin) and is

recommended in all sightseeing guides for the area.

Kletter relates that in February 1950, at the initiative

of Yeivin and others, who grasped that without government

intervention, the country's urban past would simply

disappear, Ben-Gurion agreed to establish a government

committee "for sacred and historic sites and

monuments." The committee was staffed by senior

government and military personnel. The report, which was

submitted in October 1951, stated that certain sites had

to be preserved as "whole units" - "Acre,

a few quarters in Safed, small sections of Jaffa and

Tiberias, small sections of Ramle and Lod, a few sections

of Tarshiha." The rest of the towns, and hundreds of

villages, were already lost.

However, the state institutions failed to honor even

these conclusions. According to Kletter, Yeivin was one

of the first to fight the August 1950 decision to

demolish all of Jaffa. Afterward, artists who had moved

into the abandoned city joined the struggle, as did

Development Authority personnel, and thus a few sections

were spared total annihilation. Yeivin was less

successful in Lod. In June 1954, he wrote a protest

letter to the education minister, in the wake of a

decision on "the destruction of the ancient quarter

in the city of Lod." Israeli law, pursuant to

British law, stipulated that only what was built before

1700 was considered an "antiquity," but Yeivin

wrote that the other sites should also be preserved -

both for tourism and because they are "cultural and

educational assets and living historical testimonies that

every enlightened state is obliged to preserve."

Kletter's book leaves the impression that the destruction

was not accidental and that its perpetrators were aware

of its significance. The ideological foundation of the

devastation is set forth in the August 1957 Foreign

Ministry letter sent at the behest of Golda Meir. After

the author of the document, A. Dotan, requested the

Ministry of Labor to "clear the ruins," he

specified "four types" of "ruins" and

the grounds for their destruction:

"First, it is necessary to get rid of the ruins in

the heart of Jewish communities, in important centers or

on central transportation arteries; rapid treatment must

be given to the ruins of villages whose residents are in

the country, such as Birwe, north of Shfaram, and the

ruins of Zippori; in areas where there is no development,

such as along the rail line from Jerusalem to Bar Giora,

one receives a depressing impression of a once-living

civilized land; attention must also be directed to ruins

in distinctly tourist areas, such as the ruins of the

Circassian village in Caesarea, which is intact but empty

... Accordingly, the Ministry of Labor should assume the

mission of clearing the ruins ... It should be taken into

account that the participation of nongovernmental

elements requires caution, as politically it is desirable

for the operation to be executed without anyone grasping

its political meaning."

Kletter says he was surprised to discover the scale of

the destruction, but that to some extent he understands

those who were behind the operation. The decision not to

allow the Palestinian refugees to return was unavoidable,

he believes, if the idea was to establish a Jewish state

here. Those were the rules of the game in that period, he

says, and if the Jewish community had lost in 1948, the

Arab victors would likely have treated the Jews in the

same way. And because it was impossible to preserve

hundreds of abandoned Palestinian towns and villages,

there was no choice but to demolish most of them, Kletter

maintains.

He also has nothing against the archaeologists who in the

early years of the state were concerned almost

exclusively with Jewish sites, or in the best case with

Christian or Roman sites, and ignored Muslim sites almost

completely. It is natural for researchers to be

interested first and foremost in their own culture,

Kletter says; and besides, relative to the political

pressure exerted on them by people like Ben-Gurion, who

declaredly wanted to erase the Arab past of this country,

they behaved honorably. "Early Israeli archaeology

has something to be ashamed of and much to be proud

of," Kletter writes.

Still, Kletter says, his book is "about loss, about

what could have been but was not. The loss of archaeology

that began with a scientific tradition and did not

continue, the loss of vast historical information, the

loss of the village landscape. I don't think this village

landscape belongs to us - it belongs to the people who

lived here - but still, there is longing for that lost

landscape. We cannot bring it back, but at least we

should be aware of the truth and not lie to

ourselves."

Kletter says this country's great good fortune lies in

the fact that it contains so many monuments that it was

impossible to destroy all of them. But even those that

were destroyed somehow continue to live a different life.

Mash'had Nabi Hussein, the holy site in Ashkelon, was

leveled in 1950, but the Muslim believers did not forgo

it. A few years ago, the Shi'ite Ismaili sect, which is

based in central India, established a kind of small

marble platform at the site, on the grounds of Barzilai

Hospital, and since then thousands of believers have come

there every year. In Yavneh, only the minaret remains of

the razed ancient mosque, standing alongside heaps of

rubble and one fig tree, but in a visit to the site a

week ago I saw a group of elderly Ethiopians there on the

hill, praying ardently under the fig tree. It was as if

the place had remained holy even if its inhabitants had

changed.

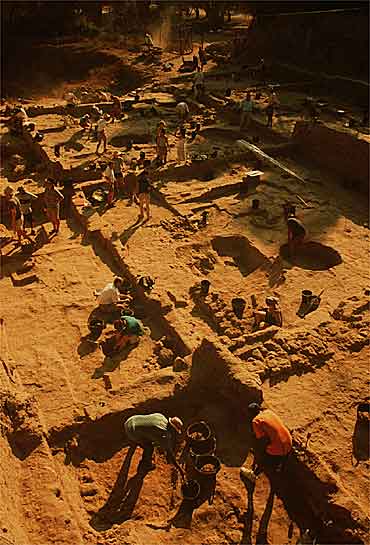

Excavators peer into the Philistine period at grid 38. About an acre in size (0.4 hectares), it is the largest of the four sections now being worked at Ashkelon. Philistines dominated the city from 1175 B.C. to 604 B.C. Enemies of the Israelites, Philistines were depicted in the Bible as brutish, but this excavation is revealing a sophisticated culture.