AUGUST 2007

The

nature of the problem is familiar enough. Belgrade is the

capital of a vanishing state that once stretched to the

Austrian border. Its peeling stucco and abandoned old

cars are emblematic of decline. Nobody needs a thousand

guesses to determine who was the big loser from

Yugoslavia's disintegration . Slovenia and Croatia have

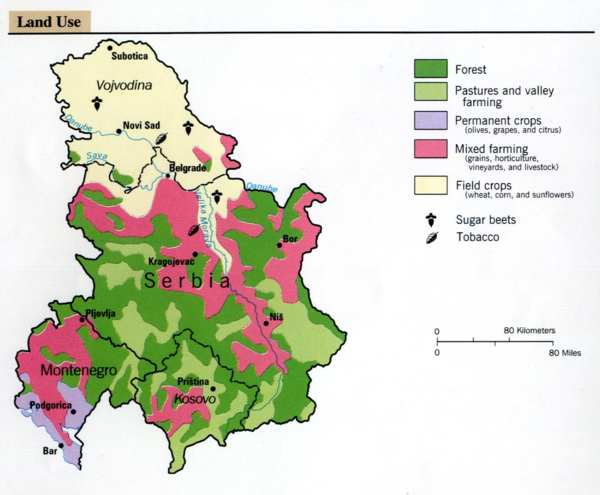

left Serbia in the dust. Note in map below the removal of

Kosovo and Montenegro leaves Serbia stranded in the

mountains.

this shows the

diminished country of Serbia - punished for standing up

against EU planned break up of Yugoslavia

MEDIA ALERT: FROM BLAIR TO BROWN -

THE KILLING WILL CONTINUE

MEDIA LENS: Correcting for the distorted vision of

the corporate media

July 23, 2007

The first truth of American foreign policy is that it is

formulated to maximise corporate profits and state power.

The second truth is that it is perennially sold to the

public as a mission to spread freedom, democracy and

human rights. The third truth is that the first two

truths apply regardless of whether the Republicans or

Democrats hold power.

But this cannot be true. After all, America led the 1999

Nato campaign to stop “the Serbian genocide

machine” in Kosovo, as the Guardian observed in

April of that year. (Peter Preston and Patrick Wintour,

‘War in the Balkans,‘ The Guardian, April 4,

1999)

Although the word genocide is rarely used now that the

basic facts have become undeniable, Kosovo continues to

be almost universally acclaimed as an example of

“humanitarian intervention”. Indeed it is used

as circumstantial evidence for the purity of US-UK

motives in Iraq. In reviewing the “legacy” of

Tony Blair, Polly Toynbee wrote:

“Abroad, Blairism was a noble ideal of liberal

interventionism: sheer force of moral argument brought a

reluctant US to the rescue of Kosovo and the downfall of

genocidal Milosevic.” (Toynbee, ‘Regrets? Too

few to mention any in particular,’ The Guardian, May

11, 2007)

Jonathan Freedland commented of Blair:

“He led the Nato alliance into what was hailed as

the first humanitarian war, the military action aimed at

saving Muslim lives from Serb aggression in Kosovo in

1999.” (Freedland, ‘The Blair years: A

contrarian and a magician,’ The Guardian, May 11,

2007)

Notice that Freedland subtly affirmed in the second half

of the sentence what he reported as merely “hailed

as” true in the first half.

Johann Hari wrote in the Independent:

“In 1997, with fears that the violence would begin

again, Blair had a naive, noble desire to stop Serbian

ultranationalism in its bloody tracks.” (Hari,

‘Blair's legacy lies in the Baghdad morgue,’

The Independent, May 14, 2007)

‘Bambi’ Blair, then, was a well-intentioned

innocent abroad. Hari felt able to write this eight

years, and many hundreds of thousands of deaths, after

Andrew Marr wrote at the height of the Kosovo war of

Blair: “I am constantly impressed, but also mildly

alarmed, by his utter lack of cynicism." (Marr,

'Hail to the chief. Sorry, Bill, but this time we're

talking about Tony,' The Observer, May 16, 1999)

Yasmin Alibhai-Brown wrote more recently:

“Robin Cook promulgated the ideals of an ethical

foreign policy and we intervened nobly in Sierra Leone,

Bosnia and Kosovo.” (Alibhai-Brown, ‘Blair's

failed promise to Britain's blacks,’ The

Independent, May 14, 2007)

"Who is this 'we' exactly that you're talking

about?” as Harold Pinter has asked so well. Is it,

perhaps, an elite journalist special forces unit? David

Aaronovitch explained in the Independent:

"Would I fight, or (more realistically) would I

countenance the possibility that members of my family

might die [for Kosovar Albanians]?"

His answer: "I think so." (Aaronovitch, 'My

country needs me,' The Independent, April 6, 1999)

The technical term for this kind of writing is:

‘independent liberal journalism.’

Keith Waterhouse responded a little unkindly in the Daily

Mail:

“David, baby, you are too old, too fat and too silly

to be allowed to handle a gun, as you well know. Throwing

Lion bars to the refugees would be about your mark.

“On the other hand, we don't want to lose you but we

think you ought to go.

“I would personally buy the tin helmet and fly him

over Kosovo in a hired helicopter if I thought the beggar

would jump.” (Waterhouse, ‘Fighting talk,‘

Daily Mail, April 8, 1999)

By contrast, John Norris, director of communications

during the Kosovo war for deputy Secretary of State

Strobe Talbott - a leading figure in State Department and

Pentagon planning for the war - commented on the real

motives. Presenting the position of the Clinton

administration, Norris wrote in his book, Collision

Course: “it was Yugoslavia’s resistance to the

broader trends of political and economic reform –

not the plight of Kosovar Albanians – that best

explains NATO’s war”. (Norris, Collision

Course: NATO, Russia, and Kosovo, Praeger, 2005, p.xiii)

Strobe Talbott noted in his foreword that “thanks to

John Norris,” anyone interested in the war in Kosovo

“will know... how events looked and felt at the time

to those of us who were involved”.

“Hence,” Noam Chomsky writes,

“Norris’s evaluation is of particular

significance for determining the motivation for the

war.” (Chomsky, Failed States, Hamish Hamilton,

2006, chap. 2, n 34)

The Balkans writer Neil Clark had earlier pointed out:

"The rump Yugoslavia... was the last economy in

central-southern Europe to be uncolonised by western

capital. ‘Socially owned enterprises’, the form

of worker self-management pioneered under Tito, still

predominated. Yugoslavia had publicly owned petroleum,

mining, car and tobacco industries, and 75% of industry

was state or socially owned.” (Clark, ‘The

spoils of another war,’ The Guardian, September 21,

2004; http://www.guardian.co.uk/Kosovo/Story/0,2763,1309165,00.html)

In the Nato bombing campaign, state-owned companies -

rather than military sites - were specifically targeted.

Nato only destroyed 14 tanks, but 372 industrial

facilities were hit - including the Zastava car plant at

Kragujevac. “Not one foreign or privately owned

factory was bombed,” Clark noted. (Ibid)

The media consensus on the humanitarian nature of the

war, then, is a fraud. Indeed, in reality, Nato’s

bombing campaign dramatically increased the scale of

atrocities against Kosovar civilians, as Nato commanders

predicted ahead of their assault.

Unsurprisingly, Norris’s words do not exist for the

liberal media - they have not been mentioned in any UK

newspaper.

This all accords well with the three truths of US policy

described above.

British Foreign Policy - Always A New Dawn

The first truth of British foreign policy is that it is

also formulated to serve elite power. The second truth is

that it is rooted in unwavering support for US policy,

including participation in attacks on defenceless Third

World targets - the reason London, not Stockholm, has

been subject to September 11-style suicide attacks.

The third truth is that this foreign policy is always

sold in a way that echoes US claims of humanitarian

intent, so lending a veneer of international legitimacy

and support. It is of course very much easier for a

“coalition” to claim to be expressing “the

will of the international community” than it is for

a rogue superpower acting alone.

The fourth truth is that these truths apply regardless of

whether Labour or Conservatives hold power.

Finally, because the collision between the reality and

appearance of policy becomes increasingly obvious over

time, the fifth truth is that a change of British

government is always said to herald a change to a more

moral foreign policy. This transformed policy is always

said to be driven by idealistic new minds acting out of

revulsion at past ’mistakes’ - the slate can

thus be wiped clean and media gullibility rebooted to the

default setting.

Thus, as Tony Blair took office in 1997, his new foreign

secretary, Robin Cook, promised a new, ethical approach:

"We will not permit the sale of arms to regimes that

might use them for internal repression or international

aggression." (Quoted, Ian Black, 'Cook gives ethics

priority,' The Guardian, May 13, 1997)

This would be part of New Labour's determination to do

nothing less than "put human rights at the heart of

our foreign policy," Cook claimed. (Ibid)

Liberal cheerleaders queued up to celebrate the

revolution. In the New Statesman in 1999, John Lloyd

looked back on “one of the boldest initiatives taken

by a major state to shift foreign policy on to new

tracks”. (Lloyd, 'Mandarins, guns and morals,' New

Statesman, October 25, 1999)

The Guardian's Hugo Young wrote of Blair: "the

grandeur of his ambition shouldn't be underestimated. He

wants to create a world none of us have known, where the

laws of political gravity are overturned.” (Young,

‘Everybody is one of us in Blair’s world,’

The Guardian, May 27, 1997) This in “the age when

ideology has surrendered entirely to 'values'."

(Young, ‘After the Blair deluge, reality steps

forward,’ The Guardian, June 17, 1997)

Even after claims of an ethical foreign policy were made

ridiculous by Blair’s wars of aggression, the myth

was simply too important to be ditched. Following Robin

Cook’s death in August 2005, former culture

secretary Chris Smith wrote in the Independent of

Cook’s foreign policy:

"It represented a brave attempt to cast our

country's relations with the rest of the world in a moral

light." (Smith, ’Robin Cook: 1946-2005, The

House of Commons was his true home,’ The

Independent, August 8, 2005)

As the piles of corpses expanded in Iraq, Labour MP Denis

MacShane wrote in the New Statesman:

“As foreign secretary, he [Cook] rescued British

foreign policy from the dead waters of failed Tory

cynicism.” (MacShane, ‘More loyal than left:

Robin Cook: a tribute,’ New Statesman, August 15,

2005)

Two years later, of course, much of the British public

perceives Blair and his government as utterly discredited

- and, by extension, the Labour party that allowed him to

remain in place while he cut a bloody swathe through the

Iraqi people.

Many in the corporate media are also only too aware that

their credibility has been shredded by their earlier

adulation of Blair, by their failure to challenge even

the most obvious government deceptions ahead of the war,

and by their cheerleading of the war before the

catastrophe became undeniable. It is not hard to

understand why the political-media system has a shared

interest in declaring a new, ethical beginning.

Gordon Brown’s Brave New World

In Gordon Brown's inaugural Downing Street speech, the

new man claimed: "I have listened and I have learned

from the British people." (http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/politics/article1996727.ece, June 28, 2007)

Brown, it seems, will bring about "change" by

sweeping away "the old politics," promising

"a new spirit of public service to make our nation

what it can be".

Perhaps this ‘New’ New Labour could be marketed

as New Labour Plus.

Echoing John Lloyd in 1999, former government adviser,

David Clark, wrote in the Guardian last week:

“Only the most implacable critics of the government

could fail to appreciate the shift in foreign policy

since Tony Blair left office three weeks ago. This was

always going to be a difficult and controversial

process.” (Clark, ‘Britain must take the lead

in Iraq - by getting out first,’ The Guardian, July

16, 2007

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/story/0,,2127227,00.html)

On the BBC’s Sunday AM programme, new British

foreign secretary David Miliband, echoing Robin Cook,

declared that the goal was for British foreign policy to

be “a force for good in the world“. Asked if

this meant Britain would distance itself from US policy,

Miliband instantly reversed the claimed priorities,

insisting that the alliance with the US was vital for

Britain’s “national interest”. (Sunday AM,

BBC 1, July 15, 2007) In other words, Miliband is playing

the traditional “double game” - the claimed

emphasis will be on “doing good”, while policy

will be rooted in the muscular realpolitik of

“national interest”. In 1937, anarchist writer

Rudolf Rocker explained the meaning of the favoured

patriotic term:

“We speak of national interests, national capital,

national spheres of interest, national honour, and

national spirit; but we forget that behind all this there

are hidden merely the selfish interests of power-loving

politicians and money-loving business men for whom the

nation is a convenient cover to hide their personal greed

and their schemes for political power from the eyes of

the world." (Rocker, Culture and Nationalism,

Michael E. Coughlan, 1978, p.253)

The same unavoidable clash between appearance and reality

is repeated across the press. An editorial in the

Guardian observed that "in a fundamental way... the

New Labour strategy that [Brown] helped create will not

change".

The editors then necessarily muddied the issue, pointing

to a "sense that something significant has

shifted" and asserting that Brown's arrival marks a

"renewal" and "the drama of a new cabinet

with a changed agenda". (Leader, 'Brown arrives: The

old and the new,' The Guardian, June 28, 2007)

Senior Guardian journalists were quick to reinforce this

vital aspect of propaganda. The Guardian's political

editor, Patrick Wintour, wrote of Brown's intention to

"rebalance Mr Blair's foreign policy", with the

introduction of "new faces and plans to heal old

wounds" aimed towards "restoring trust in

politics". (Wintour, 'Brown's first day,’ The

Guardian, June 29, 2007)

Exactly the same, of course, was declared of Robin

Cook’s rebalancing of unethical Tory policy - with

all doubters dismissed as miserable cynics. The title of

a June 1997 article by Neil Ascherson in the Independent

read: “After 18 years of national egoism, the world

has a chance to like us again.” (Ascherson, The

Independent, June 7, 1997)

Guardian assistant editor, Michael White, welcomed

"a smiling Gordon Brown" and the

"unexpected echoes of that other new beginning"

in May 1997 when Blair strode towards Downing Street

before wild throngs of Labour Party activists. (White,

'The accession,' The Guardian, June 28, 2007)

In truth there was nothing “unexpected” about

claims of another “new beginning”. Despite

being up to his neck in the Iraq bloodbath, Brown has to

claim to represent the fresh start, new direction and

clean slate that he clearly is not.

An Independent editorial claimed Brown was "breaking

with the Blair years". (Leader, 'Things can only get

better???,' The Independent, June 28, 2007)

By contrast, John Pilger was all but alone in noting the

"tsunami of unction" that "engulfed the

departure of Blair and the elevation of Brown".

(John Pilger, 'These are Brown's bombs too,' New

Statesman, July 5, 2007; http://www.newstatesman.com/200707050024)

Pilger put Blair's departure - treated by the media

almost as a state occasion - into painfully accurate

perspective: "those MPs who stood and gave him a

standing ovation finally certified parliament as a place

of minimal consequence to British democracy”. (Ibid)

Historian Mark Curtis has commented:

"Brown has been four-square behind Blair on foreign

policy, including, of course, Iraq, which he has financed

as Chancellor and publicly defended when required."

Curtis also points to Brown's "total support and

defence of big business" describing it as

"quite extraordinary and perhaps unprecedented in

the postwar years," adding:

"Virtually every speech for the last ten years has

been a reassurance to business that Labour is on its side

and a defence of 'free trade' and ensuring climates

around the world favourable for British foreign

investment, along with ongoing commitments to low

corporation taxes and cutting business regulation. Brown

is the ultimate liberalisation theologist and every one

of his policies has pushed in this direction."

(Curtis, interview, 'The future of British foreign

policy,' ukwatch.net, May 7, 2007; http://www.ukwatch.net/article/the_future_of_british_foreign_policy)

This is not allowed to matter in the combined

media-political attempt to wash the blood of Iraq from

their hands. And what will be the result if they are

allowed to succeed?

This was made clear enough last week by the

Guardian’s Jonathan Freedland who, as though

appearing in some recurring bad dream, warned, yet again,

of “a very real threat: Iran”. He added:

“Nowhere is the Iranian peril assessed more closely

than in Israel, which would, after all, be target number

one for any Iranian bomb.” (Freedland, ‘This

flurry of Middle East activity is the product of a very

real threat: Iran,’ The Guardian, July 18, 2007)

With the policy goals and the interests shaping them

unchanged, with the “necessary illusions” of

power unchanged, with the bottom-line of state-corporate

greed unchanged, the lies and killing are certain to

continue.

The novelist James Joyce commented on the endlessly

repeating cycle of human tragedy: “History is a

nightmare from which I am trying to awake.”

There is no choice - it is up to us as individuals to

wake up. That’s all there is. But what does this

mean? It means we must not allow ourselves to yet again

be deceived. In the absence of serious investigation or

evidence, we must not believe something merely on the

grounds that it is pleasant and comforting. We must not

assume that the world really is under some benign

‘new management’. Instead we must take personal

responsibility and work for real change rooted in genuine

compassion for others.

Mass killing does not originate in great drama. Ten years

ago, when journalists were so eagerly hailing

Blair’s “new dawn”, nothing very terrible

happened. People went along with it, agreed with it -

they felt they had played a virtuous role in promoting

positive change, experiencing their optimism as a

healthy, life-affirming thing. They were doubtless

relieved that they could leave it to this new, more

“ethical” group of politicians to sort out the

problems of the world so that they could 'get on with

their lives'.

And yet these responses were crucial links in a causal

chain that has since resulted in the deaths of perhaps

one million Iraqi people.

SUGGESTED ACTION

The goal of Media Lens is to promote rationality,

compassion and respect for others. If you decide to write

to journalists, we strongly urge you to maintain a

polite, non-aggressive and non-abusive tone.

Write to Jonathan Freedland

Email: freedland@guardian.co.uk

Write to Alan Rusbridger, Guardian editor

Email: alan.rusbridger@guardian.co.uk

Write to Simon Kelner, Independent editor

Email: s.kelner@independent.co.uk

Please send a copy of your emails to us

Email: editor@medialens.org

Please do NOT reply to the email address from which this

media alert originated. Please instead email us at

Email: editor@medialens.org

This media alert will shortly be archived here:

www.medialens.org/alerts/07/070723_from_blair_to.php

The Media Lens book 'Guardians of Power: The Myth Of The

Liberal Media' by David Edwards and David Cromwell (Pluto

Books, London) was published in 2006. John Pilger

described it as "The most important book about

journalism I can remember."

For further details, including reviews, interviews and

extracts, please click here:

www.medialens.org/bookshop/guardians_of_power.php

We are very happy to maintain these alerts as a free

service but please consider donating to Media Lens:

www.medialens.org/donate

Please visit the Media Lens website: www.medialens.org

Background photo Yugoslav Drama Theatre