AUGUST 2007

"In the village of Malpoolenge in Mozambique, there was one mine accident near the water pit, and the whole village moved away from their homes to live in a refugee camp … In the end they only found three more mines. So, a total of four mines in the vicinity of the water pit made 25,000 people move away from their normal habitat."

As director of the Belgian APOPO de-mining operation, Bart Weetjens witnesses every day the unique abilities of the African giant pouched rat. But he also sees the lasting effect land mines can leave on communities and people. In this interview with FRONTLINE/World reporter Alexis Bloom, he talks about how one land mine incident can force an entire community to disperse. He also addresses the obstacles he faced in getting the program running and argues that rats are a misunderstood species.

Q: Alexis Bloom: Bart, how would you describe the

ideal APOPO rat?

A: Bart Weetjens: The ideal rat is one that is not too

nervous and one with an extremely keen sense of smell,

because there’s a huge variation between animals.

Not all rats are suitable to work as mine detectors. It

also has very stable behavior and interacts well with

human beings.

Q: Can you explain the process of demining and how the

rats operate?

A: The rats work in sections, 100 square meters at a

time. They are 5-by-20-meter or 10-by-10-meter boxes.

Each box takes about 25 to 30 minutes to get through. As

a comparison, a miner would be able to get through about

50 square meters a day.

Q: So when they smell that explosive in the ground,

they think they’re going to get food?

A: Yeah, they associate this particular explosive scent

with the food they want.

Q: Sort of like Pavlov’s dog?

A: Well, yes and no. It’s classic conditioning. We

associate a click sound with the food reward. Once an

animal knows that the click means food, whatever behavior

it does to get that click, it will repeat because it

knows it will get food.

Q: Couldn’t that be a problem, though? They could

just scratch randomly to get the food reward instead of

indicating the presence of explosives.

A: They don’t, though. Animals are far more honest

than humans. These rats, they’re just …

they’re nice creatures. There’s a lot of

misperception about rats. And that originates from the

Middle Ages, when rats were accused of transmitting

plague -- which is, by the way, not true. It was the

fleas on the rats that transmitted the plague, not the

rats. The rats were just victims. Of course, they do

destroy crops and do transmit diseases. But if you treat

them well and give them the proper housing and the proper

care, they are actually very organized, neat animals.

They’re very kind also, and they have very complex

social structures.

Q: With your history and training as a product

designer, where does your interest in working with mine

detection rats come from?

A: When I was a boy, I had a passion for rodents. One day

I was given a hamster, and I was so fond of this hamster

that I gave it another hamster as a playmate. Soon, I had

a lot of hamsters. And I also brought in some rats, some

gerbils, some mice -- which I kept until I was about 14

years old.

Q: How did that early interest turn into your

life’s work?

A: Well, I was working as a product engineer, designing

coaches, travel buses, and I wasn’t really happy

there. I didn’t really feel like I was contributing

to the real world. At the same time, in the ’90s,

there was this growing consciousness of the land mine

problem and the devastating consequences of land mines in

Africa. I decided that’s what I wanted to work on,

so I gave up my job and started focusing on the land mine

problem. I visited Angola and Mozambique, and I saw, for

instance in Mozambique, land mine detection groups

working with dogs. They had lots of problems with the

dogs, particularly health problems. They had brought in

20 dogs, and after three months they only had 13 left.

Seven dogs died from disease. At that moment I

hadn’t made the link yet towards rats. That happened

only after reading articles of American scientists who,

in the ’70s, had trained gerbils for the purpose of

explosive detection in airports. That for me was a match.

Of course rats could do that job.

Q. How did people respond to your idea about using

rats? Did you have to overcome prejudices?

A: Yeah, lots; in the beginning it was really tough.

Everywhere I went to apply for funding, we were just

laughed at. Most institutions were very, very reluctant

[to sponsor] such an approach. But I got support from

professors at Antwerp University. And, via the vice

chancellor, we also got access to the Development

Corporation desk in Brussels, who finally gave us a

one-year grant. Not a huge grant but sufficient for us to

start, to prove that it would be possible. With that

first grant, we imported rats from Tanzania and started a

breeding program in Belgium. The youngsters we started

making hand-tame. In the meantime, we tried out different

species of rats and all different training protocols. And

when we applied them to the African giant rat, we were

successful. After two years, we had sufficient proof to

bring the program to Tanzania and to continue developing

it with the Africans.

Q: Why did the African giant rat work? What is it

about their behavior?

A: Well, for example, when we reward them with peanuts,

they don’t eat them immediately. They keep them in

their pouches until they reach their nest box and then

bury them there to store for later. And in rainy season,

when food is plenty, they go around and collect a lot of

food in their pouches and store it underground in

burrows. Later, in dry season, when food is scarce, they

can find their way back to these stores with only their

sense of smell. So this is very close to land mine

detection.

Q: In addition to the direct detection system of

identifying contaminated areas on site, you also run a

remote tracing system. Can you tell us about that?

A: The system is called REST, for Remote Explosives Scent

Tracing, and it can hopefully speed up the whole demining

process incredibly. Let me tell you, about 95 percent of

a suspected area doesn’t contain any mines or

explosives at all. So, if you can open these areas,

already, 95 percent of the problem is resolved. In order

to do this -- and rather than going [physically]

everywhere, which takes a huge amount of time -- we have

conceived of this system, which consists of taking a

sample in an area, bringing it to the lab and letting the

rats analyze it. When several rats in a row say this

sample doesn’t contain any explosives, we can take

it for granted that the stretch of road doesn’t

contain mines, bombs and so on.

There is huge potential for quickly scanning vast road networks across Africa, which is especially important because the roads provide access to the villages. With an open road network, people can resume economic activity. So road infrastructure is essential in development, especially in Africa, where already there is a fragile infrastructure.

So say, for example, you have about 4,000 kilometers of suspected roads. If you have to clear all of these manually, it’ll take a few hundred years. This system is an attempt to find technology that can deal with the problem in a very fast way. For every 100-meter stretch, we take one sample and bring it back to the lab, so every sample corresponds with a stretch of road. The animals are actually opening the road by saying there are no explosives here; there is no danger, which is also the case in more than 95 percent of the suspected area.

Q: So you’re saying that a lot of the areas do

not have mines in them but, because a mine might have

been found one day close by, that whole area is

[abandoned -- or suspected]?

A: Yes, indeed, and there are numerous examples of it.

For instance, in the village of Malpoolenge in

Mozambique, there was one mine accident near the water

pit, and the whole village, which consisted of 25,000

people, moved away from their homes to live in a refugee

camp. It was, of course, a priority area, so it was also

cleared pretty fast. But in the end they only found three

more mines. So, a total of four mines in the vicinity of

the water pit made 25,000 people move away from their

normal habitat. So the consequences, the humanitarian

consequences, are huge.

Q: Have you ever known anybody who has lost a limb due

to a land mine?

A: Yeah, sure, in Angola even more than Mozambique. For

the moment in Mozambique, there aren’t as many

accidents anymore because the problem has been properly

met. However, in Angola, for instance, 0.5 percent of the

population -- that is, one in every 500 people -- has had

some sort of mine accident and either suffers from an

amputation or has lost a finger or eyesight. So the

impact of mines on society is huge. Being able to help

these people return to their villages and resume their

normal lives -- accessing their acres and accessing their

water sources, and just seeing that life can be normal

again -- I think that is the most rewarding motivation.

Q: Do you see other countries and peoples being able

one day to replicate this project without your expertise?

A: It is our wish that this project will replicate itself

somehow. There is already an example, though it is not on

the African continent but in Colombia. They have a huge

land mine problem, being the worst mined country in Latin

America. The Colombian police asked us a few questions

and then started a program themselves to train rats for

the purpose of land mine detection. So it is a hope and

has already begun realizing itself.

Q. What is the biggest challenge?

A: The main challenge for APOPO is to replicate this on a

huge scale. We get lots of demands from all over the

world -- Lebanon, Afghanistan, Libya, Senegal, all the

eleven Great Lakes region countries [of Africa], but also

Asian counties like Sri Lanka, Cambodia -- we cannot

comply with all these requests. We will be happy to be

able this year to start a second operation. So it's like

a drip on a hot plate. Well, not really, because what we

do makes a difference, but it goes way too slow. So if we

could make this a profitable business, owned locally and

made in a sustainable way, we could make a much bigger

impact.

**************************************************************************

Dolittle's Raiders

DAVID STIPP / Fortune 2may2005

There's a rat loose here at the Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., and it's coming right at me. Suddenly it veers and goes back the way it came. Then it loops around and darts toward me again. It seems to be one dizzy rodent. But it's not. Its movements are being directed by a higher power — I'm playing with its mind by remote control.

Rat No. 3, as she's known, is wearing a tiny backpack crammed with electronics from which several wires lead into her brain through a plastic cap on her head. When I press a personal computer's cursor-control keys, radio signals are transmitted to the backpack, which in turn sends electrical impulses to the parts of her brain that register sensory input from her whiskers. Neuroscientist John Chapin and colleagues here have taught her to go left when her brain's left-whisker area is stimulated, and right upon a right-side tweak. Their training method resembles teaching a dog to roll over: When No. 3 moves as directed, they stimulate her brain's "reward" center through a third wire — like giving a treat to Rover.

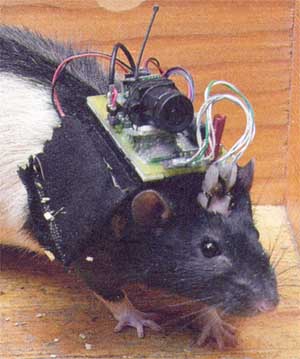

The most important thing she's learning is that explosives have yummy aromas. More on that process later. But first the why: "Roborats" like No. 3 may someday be the terrorist's worst nightmare — keen, furtive little spies that can be guided into a building through, say, an air duct and then allowed to roam freely to sniff out explosives, toxic chemicals, or other bad stuff. The team at the Brooklyn center, part of the State University of New York, has even mounted tiny cameras on roborats' backs, enabling remote handlers to see where their furry operatives are going — and what they're finding.

You don't have to think very far out of the box to grasp the attractions of small, cheap, fast-reproducing animals as bomb sniffers. In recent years the Department of Defense has sought to enlist a number of nosy little creatures for the perilous job, including rats, wasps, honeybees, and even yeast (yes, yeast). The program is still a work in progress. But it has shown in fascinating detail that dogs are not the only Einsteins of olfaction, nor necessarily the best animals for nosing out explosives.

Unlike dogs, small animals can walk (or fly) over land mines without setting them off. Bees don't get hip dysplasia. Sniffer dogs need frequent rests; wasps don't. And it's a lot easier to come by insects and rodents than the purebred dogs preferred by bomb squads. In fact the market for sniffer dogs has gotten so hot since 9/11 that con artists have moved in: In 2003 the owner of a Virginia kennel was convicted of fraud after he charged federal agencies more than $700,000 for a pack of clueless pooches. In one test they allegedly failed to detect a huge cache of explosives hidden in vehicles right in front of their schnozzes. Bad dogs.

Most of the studies on non-dog sniffers have been funded by the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, an elite force permanently deployed on the border between science and science fiction. A few years ago, says Alan Rudolph, who formerly oversaw DARPA's sniffer-critter projects, it occurred to agency scientists that species whose survival has depended for millions of years on the ability to scent mates and food should have olfactory senses at least as keen as dogs'. Soon after, Rudolph, now CEO of Adlyfe, a Rockville, Md., biotech, began enlisting animal-olfaction experts to see if their favorite beasts could be taught to associate the aroma of explosives with things to which they're attracted.