FEBRUARY2007

Wheels within 'wheels wherein the fluctuation of who is your friend/your enemy changes

results

in History analysis

Today in Iraq there is a holocaust

happening before your very eyes.

Data from http://www.h-net.msu.edu/~holoweb/logs/May95.html

, from Soviet Encyclopedia of Literature and Rense.com

The Teacher:

I've become rather demoralized after trying, in vain, to

help the students in my Holocaust seminar understand

whatI see (at this point in my life, anyway) as one of

the only tangible and legitimate lessons that those of us

who "weren't there" can learn from the

Holocaust: to wit, the extent to which ordinary people

can help to promote and can even commit acts of

extraordinary evil, and the extent to which we ourselves

are ordinary people. The violence is in us; it is

internal, mimetic, and contagious, as Rene Girard, Thich

Nhat Hanh, Martin Luther King,Ghandi, and so many others

have tried to teach us. Still, the bulk of my

students--after reading so much material on the

Holocaust, after listening tosurvivors, liberators, and

rescuers, after seeing the films, after visiting Mel

Mermelstein's private exhibit--seem either unable or

unwilling to understand the deeply profound and, yes,

deeply personal issues at stake here.

I tried helping them understand these issues by, among other things, explaining that, after initially and mistakenly imagining that the Oklahoma City terrorist(s) must be Middle Eastern and Islamic (that is, "not one of us"), we came to discover that McVeigh is indeed--well, what do you know?--one of "us." Immediately, I went on, "we" began distancing ourselves from him ("Well, he's not *really* one of us; he's actually quite different....") Then, when I further tried explaining how calling for his death engages us in the very violence that we claim to be so appalled at and to want to end--that it helps to support the contention that violence is contagious, mimetic, and internal, and that it helps confirm the notion that all of us participate in acts of violence--I received little more than angry resistance and denial.

Never mind the fact that, at the time, we were studying the work of Milgram and Browning. Never mind the fact that I asked my students to think hard about what they thought Wiesel (I *think* that the following notion is Wiesel's; please correct me if I'm wrong) meant when he said something (and here I'm paraphrasing) that perhaps the worst crime that the Nazis committed against the Jews is that they turned the Jews into killers.

Yes, there are differences among different acts of violence, and there certainly are differences among us all. No doubt about that. But it is not for nothing that a survivor whom I recently interviewed wrote a book entitled_Are We All Nazis?_ Even if violence can be or *seemingly* can be justified, it is a disease, andits use spreads the disease. Violence never works to establish lasting peace. Socrates knew that. Frankl knew that. Wiesel knows that. Do we?

Richard Prystowsky (RJPrys@aol.com)

School of Humanities and Languages

Irvine Valley College

5500 Irvine Center Drive

Irvine, CA 92720

Phone: 714-559-3206

Fax: 714-559-3270

The Artist:

"What do we do with all this research and study and

concern?" I have never heard or come up with a good

answer to such questions, except for this, that the

alternative to the attempt to do something is

unacceptable. We have no guarantees, or much evidence at

all, that teaching about the Holocaust or racism or Pol

Pot will do anything to prevent repetition of inhumanity

and atrocity. But I can not help but think that if no one

preserves, analyzes, talks, and teaches about this

spectrum of culture (an unfortuate part of culture, to

say the least), then the tide of human behavior as refuse

will completely drown us all. I have often wondered why I

focus my art work on the Holocaust and Eastern European

Jewish culture, when I could actually be making a living

painting portrait commissions and chronicaling the

Industrial Revolution in the United States. Just as with

other people I know who seriously focus on such subjects,

doing so feels like a mandate. If we do not make art and

poetry and educate as best we can after Auschwitz, then

the barbarians will have truly won. H.L Sepinwal

The Writer:

From: T. L. Dale < Dykola@AOL.COM >

I for one must say that growing up I found the attrocities of WW2 to be very interesting. It interested me that (as a 12 year old) one man could accumulate such horrific power and be able to attain death at his fingertips for anyone HE saw fit. I have carried this interest on with me in life, and it has branched on to "smaller" effects...such as child abuse (sexual and physical) and so on. I, as a writer, have done some pieces on aspects of the holocaust, on Vietnam, and on child/physical/sexual abuse (in all aspects of life). In allthese pieces that I have written, I have tried to get them to a larger audience. Often times, I find that people do not wish to publish them as they hit to close to home...yet, if we do not convey the actual feelings of what has happened to people in the past and present, how can we expect anyoneto understand?

.................................................................................................................

From: Franklin Littell < FHL@TEMPLEVM >

Colleagues: I am grateful to Charles

Fishman for his information on use of the word

"Holocaust." The forthcoming issue of HOLOCAUST

AND GENOCIDE STUDIES will carry an article of mine in

which i.a. I discuss my own experience with this word. I

remember hearing Elie Wiesel and Raul Hilberg discussing

one time which of them introduced it - NIGHT in 1958 or

THE DESTRUCTION OF EUROPEAN JEWRY in 1961? Two summers

ago a German scholar working in my papers from my years

with OMGUS discovered it used in a "Newsletter"

I was mimeographing and sending to colleagues back home -

from Stuttgart in August, 1949. On reflection I concluded

I must have picked it up - as a precise reference to the

Nazi genocide of the Jews - from American Jewish

chaplains or from workers in the DP camps. In any case, I

concluded in my paper: "The `Holocaust' was not

`invented,' as the revisionists claim... we looked back

and it was there - as close, as inescapable, as our own

shadows." - Franklin Littell

*****

The noun 'holocaust' in the English language has been

traditionally defined for at least 750 years as a

religious sacrifice on a large scale, usually by fire, a

'burnt offering'. During the past 200 years,the term

began to denote the massacre of a large and usually

defenseless group of people. This secular sense of the

term became quite popular in the 19th century. It is

therefore not surprising to find the term applied to

descriptions of massacres of Jews, as in the 1855

reference you cite, as well as non-Jews (eg.L.Ritchie, WANDERING

BY THE LOIRE,1833:"Louis VII once made a holocaust

of thirteen hundred persons in a church").Michael

Thaler

*****

Burt Bledstein < bjb@uic.edu > Holocaust Etymology: comment

- "THE Holocaust," representing an identifying historical event--mass murder of Jews by Nazis--was accepted by scholars (primarily Jewish) in the 1950s, not earlier.

- Prior usage of the phrase "holocaust" without "THE" specific article was casual, identifying sundry incidents and occurrences. Jews in prior usage were not habitually identified as the primary object of "holocaust" slaughter.

- Usage of the phrase before the 17th c. meant sacrifice, a whole burnt offering, often martyrdom. Holocaust was a cleansing act leading to a form of redemption. More secular references after the 17th c. pointed to incidents of slaughter, massacre, and destruction by means of a total consumption of fire without religious significance.

- The representation "THE Holocaust" in the 1950s elevated it to a specific a historical event of monumental proportions, beyond a series of occurrences and random references. It also turned the meaning back to the sacrificial act of a whole burnt offering. "THE Holocaust" of the Jews by the Nazis was the first scene in the drama of a foundational myth in which the birth of the State of Israel followed as a redemptive act.

The counterfactual argument is intriguing. Without Israel would the phrase have been adopted in the 1950s to characterize the event of the previous decade? Without acceptance of "THE Holocaust" in the 1950s, would there be any interest in the casual prior usage?

*****

"In a world of absurdity, we must invent

reason; we must create beauty out of nothingness." -

Elie Wiesel

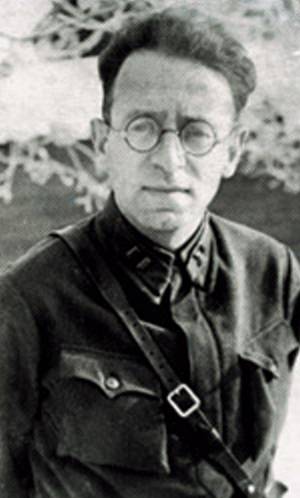

- Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg

January 27,(14 Jan, Old Style) 1891 - August 31, 1967

(Ehrenburg's second volume of poetry was published in 1911. It again contained Catholic poems, but also "To the Jewish People", a poem voicing despair over the historical plight of the Jews. During this time, Ehrenburg spent most of his time at the cafe Rotonde, whose clientel also included Picasso, Apollinaire, Diego Rivera, Juan Gris, Jean Cocteau, Modigliana, and Marc Chagall. When World War I broke out, Ehrenburg tried to enlist in the French army, but he was rejected as being too gaunt. Instead, Ehrenburg wound up working as a war correspondent for the Russian papers Utro Rossii and Birzhoviye Vedomosti. His reporting was intelligent, skeptical, and fair. His coverage of the French army's shameless use of bewildered Senegalese troops in the most exposed positions so infuriated the French government, that Ehrenburg was almost expelled from the country.The war took a toll on Ehrenburg, and he suffered a nervous breakdown. He began to yearn for his homeland, and after the February Revolution, he set back for Russia. He arrived in Petrograd just after the July days. His political leanings at the time were in favor of Kerensky, not the Bolsheviks. He moved on to Moscow where he met the October Revolution by cowering in his room as street fighting raged outside his window.In early 1918, Ehrenburg published a collection of verse entitled A Prayer for Russia (Molitva o Rossy).Mayakovsky denounced the collection as "tiresome prose printed in verses" and Ehrenburg as "a frightened intellectual".Throughout 1918 Ehrenburg wrote anti-Bolshevik articles, calling Lenin "a stocky bald man" who resembles "a good-natured burgher." He called Kamenev and Zinoviev "high priests" who "prayed to the god Lenin".

In 1919, things got too hot in Moscow for Ehrenburg, so he moved to his home town of Kiev. He met and associated with various writers including Andrei Sobol and Osip Mandelshtam. September 1919, the Whites took control of Kiev, and Ehrenburg resumed publishing hate-filled anti-Bolshevik articles, calling Lenin's revolution a "drunken orgy", the Bolsheviks "rapists and conquerors". This attitude, however, did not appease the fiercely anti-Semitic Whites. They came looking for the Jew Ehrenburg at a newspaper office once, but the printers hid him. So Ehrenburg fled to the Crimea with his wife and his mistress and from there returned to Moscow.Resuming his literary life, Ehrenburg hob-nobbed with the usual suspects--Andrei Bely, Boris Pasternak, Sergei Esenin, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Marina Tsvetaeva, Osip Mandelstam, etc., etc. He was just barely surviving by doing readings and literary reviews. Then he found a real job supervising the nation's children's theaters for the Ministry of Education. His direct superior was Vsevolod Meyerhold.Still, life was hard and, once again with Bukharin's help, Ehrenburg was one of the first Soviet intellectuals to be granted a passport to travel abroad. Ehrenburg wound up in Belgium where he sat down and in 28 days turned out his first novel The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurenita and His Disciples (Neobychainiye Pokhozhdeniye Khulio Khurenito). In the novel, the mysterious Mexican Julio Jurenito meets up with a fictional Ilya Ehrenburg and several other disciples, who follow him on a quest to disrupt Europe, undermining its myths and complacent assumptions about religion, politics, love, marriage, art, socialism, and the rules of war. The Pope is lampooned, as it the eternal internal bickering among socialist factions. Eerily, the Nazi Final Solution is presaged as Julio sends out invitations to the extermination of the Jewish tribe. In Moscow, Jurenito meets with a Bolshevik leader obviously meant to represent Lenin. This fictional Lenin shows himself to be ruthless, vowing to exterminate all enemies.

In 1928, he published Conspiracy of Equals

(Zagovor Ravnykh), a historical novel concerning

the Babeuf movement in Revolutionary France, which

rejected terror and advocated an egalitarian democracy.

Stalin did not like this work, dismissing it as

"pulp literature" suitable for "a real

bourgeois chamber theater."

In the face of the increasing criticism from Moscow,

Ehrenburg gradually began to shift his writings into a

more openly pro-Soviet direction. He wrote about European

peasants, blasted Poland's authoritarian rule and

France's racist colonialism. He undertook a series of

stories and novels exposing the greed of noted wealthy

entrepreneurs. The Life of the Automobile

focused on Andre Citroen, Pierpont Morgan, and Henry

Ford. The Shoe King attacked Tomas Bata, a

Czech footwear capitalist. Factory of Dreams

takes on Hollywood, George Eastman, and the Kodak camera.

The Single Front takes as its target Ior

Kreuger, the Swedish Match King. The capitalists were not

amused. Bata sued Ehrenburg, and Kreuger opened a public

relations war against the writer. Moscow wasn't

particularly thrilled either, however. While these books

exposed abused of capitalism, they failed to suggest

communist as the solution to these ills. The 1931 edition

of the Small Soviet Encyclopedia described

Ehrenburg thusly:

He ridicules Western capitalism and the bourgeoisie with genuine wit. But he does not believe in communism or the proletariat's creative strength.

In 1931 Ehrenburg visited Germany twice. The rise of

Nazism which he saw there gravely disturbed him. It

seemed to him that war was inevitable and he could no

longer remain an uncommitted skeptic because, as he wrote

later, "Between us and the Fascits there was not

even a narrow strip of no-man's land."

In 1932, Ehrenburg became a reporter for Izvestiya,

covering the trial of a deranged Russian emigre who had

assassinated the French President. In addition, hHis

articles were persistent and clear in calling attention

to the danger of the rise of fascism.

In 1934, Ehrenburg convinced French writer Andre

Malraux to accompany him back to the Soviet Union to

attend the first Soviet Writers' Congress. Ehrenburg was

on the presidium of the Congress and chaired several of

its sessions. In his main speech to the Congress, he

defended the need for books that appealed only to

"the intelligentsia and an elite among the

workers" and may not be understandable to the broad

masses. He spoke in praise of Isaak Babel

and Boris Pasternak and added his voice to the pleas for

greater tolerance of artistic literature.Ehrenburg was a

participant and one of the principal organizers of the

International Writers' Congress in Defense of Culture,

which began its work on 21 June 1935. The goal of the

congress was to organize a broad anti-fascist coalition

of writers from a wide range of perspectives--liberal,

socialist, communist, Christian, and Surrealist.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out in summer 1936,

Ehrenburg immediately dashed to Spain to report on the

war, disobeying instructions from Izvestiya, which

wanted him to stay put in Paris. His reporting was

intelligent and passionate, maintaining a constant

drumbeat of anti-Fascism. While in Spain, Ehrenburg also

got to meet yet another literary luminary--Ernest

Hemingway. By 1937, he put together a book of sketches on

the war entitled What A Man Needs.

On the orders of Stalin, he was given a ticket to attend

the trial of his old friend Nikolai Bukharin. Izvestia

wanted him to write an article on the trial, but

Ehrenburg adamately refused. Unknown to Ehrenburg at the

time, Karl Radek, one of the Bukharin's co-defendants,

had revealed under "interrogation" that

Ehrenburg had been present while Radek and Bukharin were

plotting their coup.

Fearful and tired of waiting, Ehrenburg sent an appeal to

Stalin, asking to be sent back to Spain. The request was

refused. Knowing that he was being extremely foolhardy,

Ehrenburg decided to "play the lottery" and

sent a second appeal to Stalin which--no one knows

why--was granted this time.Back in Europe, Ehrenburg

continued writing dispatches from Spain and France. Then

he suffered a severe shock in August 1939 with the

announcement of the Hitler-Stalin pact. He was so shaken

that for eight months he could only take in liquids and

chew on herbs and vegetables. He lost 40 pounds.Because

of the Soviet-Nazi alliance, Izvestia no longer

printed Ehrenburg's articles, knowing his anti-Fascist

sentiments. He did manage to print a series of articles

in the newspaper Trud, which, despite numerous

cuts and amendments, made his unpopular position clear.

In early 1941 Ehrenburg completed the first part of his

novel The Fall of Paris (Padeniye

Parizha), covering France in the prewar years and the

French decision not to intervene in Spain. There were no

Germans in the story yet, and by changing the word

"fascist" to "reactionary", the

journal Znamya was able to print the work. The

second part of the novel, however, was rejected.

Undeterred, Ehrenburg sent a manuscript to Stalin, who

then telephoned Ehreburg signalling his approval. The

rest of the novel was published, and various journals

started calling Ehrenburg with solicitations. In April

1942, the novel won the Stalin Prize.

)

- He was a prolific writer, celebrated author of various novels and other works of fiction. He was the top Soviet propagandist during the Second World War. He was a notorious liar and a pathological monster.As a a leading member of the Soviet-sponsored Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, Ilya Ehrenburg appeared at fund-raising rallies in the United States, raising support for the Communist cause while displaying fake bars of soap allegedly manufactured by the Germans from the corpses of dead Jews.

- But Ehrenburg was perhaps most notorious for his viciously anti-German hate propaganda in World War II.

When Hitler staged the sneak attack on the Soviet

Union in June 1941, Ehrenburg was released as a ferocious

literary weapon of war. During the war, he wrote over

two thousand articles, mainly for the paper Krasnaya

Zvezda. He gained credibility and popularity among

the troops by frankly assessing German strength and

admitting Soviet losses as well as expressing fierce

hatred for the enemy. In one of his most famous articles

he wrote:

Now we understand the Germans are not human. Now the word "German" has become the most terrible curse. Let us not speak. Let us not be indignant. Let us kill. If you do not kill a German, a German will kill you. He will carry away your family, and torture them in his damned Germany. If you have killed one German, kill another.

- In it, he exhorted Soviet troops to kill all Germans they encountered without pity.

- This is typical of the steady diet of pathological hate fed to millions of Soviet troops by this Jew, safely ensconced far from the front.

- But it wasn't only the ordinary German soldier Ehrenburg was talking about, whom he accused of the very atrocities the Communists were themselves committing. Ehrenburg's incendiary writings were, in fact, a prime motivating factor in the orgy of murder and rape against the civilian population that took place as Soviet troops rampaged into the heart of Europe. Appealing to the lowest, most subhuman instincts of this Bolshevik horde, he reiterated his genocidal message:

- "Kill! Follow the precepts of

Comrade Stalin. Stamp out the fascist beast once

and for all in its lair! Use force and break the

racial pride of these German women. Take them as

your lawful booty. Kill! As you storm onward,

kill, you gallant soldiers of the Red Army."

Soldiers loved his articles. An order was passed

not to use copies of Ehrenburg's articles for

rolling cigarettes. Molotov reported that

Ehrenburg "was worth several

divisions". On May Day 1944, Ehrenburg

received the Lenin Prive for his wartime efforts.

At least one Soviet officer, however, felt that Ehrenburg's articles went too far and incited Soviet troops to senseless violence, killing Germans trying to surrender. This officer, Lev Kopelev, was arrested and charged with "bourgeois propaganda" and "pity for the enemy".

- A true European snob, Ehrenburg was

completely dismissive of the American war effort.

According to Harrison Salibury, Ehrenburg thought

Americans were "a naive, ignorant,

uneducated colonial people who had no

appreciation for European culture." American

reporter Henry Shapiro wrote that Ehrenburg

claimed the only contributions Americans ever

made to civilization where Hemingway and

Chesterfield cigarettes, which Ehrenburg was

constantly trying to bum.

He grudgingly came to admire America's technology, privately admitting to a friend that "Europe was two hundred years bechind the United States." But his impression of Americans as crass and boorish remained.

Once back in Moscow, Ehrenburg quickly jumped into the cold war propaganda battle. He denounced the United States' Voice of America broadcasts in an article entitled "False Voice". In a small volume named In America he attacked the racial problems in the U.S. And in 1948 he wrote a play, Lion in the Square (Lev na Ploshchadi), a blistering, vicious attack on the behavior of Americans in post-war Europe.In 1950 Ehrenburg went on a propoganda junket to western Europe. For the first time, by his own admission, Ehrenburg was made to sweat by the hard-hitting questions of western journalists, particularly on questions relating to the Jewish situation. He tried to answer with ambiguities and generalities without having to resort to outright lies. But in this, he was not always successful.

Anti-Jewish hysteria reached a new high in January 1953 with the announcement of the so-called Doctors' Plot. In mid-February, Ehrenburg and many other prominent Jews were asked to sign an open letter to Stalin acknowledging the passions aroused by the Doctors' Plot and asking Stalin to round up all the Jews and send them to Siberia for their own safety. Dozens of Jewish writers, artists and musicians, including Vasily Grossman and Margaritat Aliger--all terrified--signed the letter. Ehrenburg refused three times. He then wrote a letter to Stalin arguing not the morality of the idea, but worrying that shipping all the Jews off to Siberia would be a public relations disaster for the Soviet Union in the eyes of the West. Fortunately for everyone, Stalin suddenly died and the whole idea was forgotten.

Ehrenburg worked to ressurect Babel's reputation, writing an introduction to a collection of Babel stories which, after some struggle, was published in 1957. He did the same for a collection of Tsvetaev and continued his vocal support for Pasternak as well as some of the better know of the repressed Jewish writers. He worked on a committee looking into the possibility of republishing the work of Boris Pilnyak. As a member of the editorial board of the journal Foreign Literature (Inostrannaya Literatura) he pushed for publication of the works of Hemingway and Faulkner. Ehrenburg was also instrumental in organizing the first-ever exhibit of Picasso's works in Moscow in 1956. Ten years later, in 1966, it was Ehrenburg who flew to France to award Picasso the Lenin Peace Prize.

In 1957 Ehrenburg penned an influential essay, "The Lessons of Stendhal". Ehrenburg used Stendhal's remarks about tyranny as a not-too-subtle swipe at renewed calls for conformity and limits for writers.

With each new chapter of his memoirs, publication

became more and more difficult. Ehrenburg was forced to

make many changes and deletions. Explicit references to

Bukharin were forbidden. At one point, further

publication seemed impossible when Ehrenburg was

subjected to fierce criticism from both Party ideologist

Leonid Ilichev and boss Khrushchev. But as in so many

things, Khrushchev later changed his mind, blaming

everything on somebody else. People, Years, Life

resumed publication, albeit with a preface from the

publisher accusing Ehrenburg of "violations of

historical truth."

Ehrenburg lent support to younger writers. He signed a

letter in support of Iosif Brodsky, counseled Andrei

Voznesensky on how best to avoid complications, protested

against the sentences given to Sinyavsky and Danil, and

expressed positive views about Solzhenitsyn, although the

future renegade lated lied about this, claiming that

Ehrenburg "hated" his work.

Ehrenburg continued to work on his memoirs until just

weeks before his death. Following the writers's death,

Andrei Tarkovsky tried to get these final pages

published, but authorities demanded so many cuts and

revisions, that the writer's family withdrew the

manuscript rather than see an eviscerated version

printed. It wasn't until 1990 that these pages were

finally published

Beset with prostate and bladder cancer, Ilya G. Ehrenburg

died on 31 August 1967.

Besides his undeniable talent as a writer, Ehrenburg had

a remarkable ability to survive. According to the logic

of the times through which he lived, Ehrenburg should

have been executed at least three or four times. But, as

Yevgeny Yevtushenko said, Ehrenburg "taught us all

how to survive." A life full of changes and

contradictions surely was his. But perhaps Ehrenburg

himself described it best in his memoirs:

If within a lifetime a man changes his skin an infinite number of times, almost as often as his suits, he still does not change his heart; he has but one.

- The crowning achievement of Ehrenburg's career came on December 22, 1944, when this hate-crazed fiend became the first person to mention the kabbalistic figure of Six Million alleged Jewish victims of National Socialism, and then proceeded to introduce that figure into Soviet propaganda.

- After the war he joined with co-racial and fellow propagandist Vasily (Iosif Solomonovich) Grossman to produce a fictitious "Black Book" and lay the foundation for what has come to be known as "The Holocaust."** The rest is history.

From: arieh.lebowitz < arieh.lebowitz@rex.com >

Just a thought, but it would be likely that the German authiorities, who were so meticulous about record-keeping in other ways, would have kept records of non-Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, political opponents, Jehovah's Witnesses, and I would even imagine that they would hav ekept categorized records. Who on the list has information on all of those German/Nazi archives that were hurriedly microfilmed and then packed back to Germany not too long ago?

From: Michael Thaler <mmt@itsa.ucsf.EDU>

The "Nazi/German archives" you inquire about

contain predominantly Nazi Party and SS membership

records. These were kept in the Berlin Documentation

Center under the jurisdiction of the US Armed Forces

until last

summer when control was turned over to German

authorities. Prior to transfer from American to German

control, all files were microfilmed and the copies

brought to the National Archives in Washington, The first

4,000 microfilmed dossiers were recently made available

for public inspection.

Grossman, Vasili Semenovich.

(pseudonym of Iosif Solomonovich Grossman). Born

12 December 1905 (29 November, Old Style) in

Berdichev in Ukraine. His father was a chemical

engineer, and his mother a teacher of French.

Grossman's parents separated, and he lived with

his mother. In 1921, however, Grossman went to

live with his father in Kiev so that he could

attend the Kiev Higher Institute of Soviet

Education. Later, Grossman moved to Moscow where

he studied physics and mathematics at university. Grossman, Vasili Semenovich.

(pseudonym of Iosif Solomonovich Grossman). Born

12 December 1905 (29 November, Old Style) in

Berdichev in Ukraine. His father was a chemical

engineer, and his mother a teacher of French.

Grossman's parents separated, and he lived with

his mother. In 1921, however, Grossman went to

live with his father in Kiev so that he could

attend the Kiev Higher Institute of Soviet

Education. Later, Grossman moved to Moscow where

he studied physics and mathematics at university.While at Moscow University, Grossman began to develop an interest in writing. On 22 January 1928, Grossman married Anna (Galia) Petrovna Matsuk, a beautiful woman from a Cossack family. The couple, however, mainly lived apart, Anna in Kiev and Grossman in Moscow. After graduating from the university in 1929, Grossman went to work as an engineer-chemist in the Donbass region. He also did some work for the newspaper Literary Donbass. In January 1930, Grossman and Anna's daughter, Katya, was born. In 1931, Grossman contracted tuberculosis. He spent some time at a sanitorium in Sukhumi, then moved back to Moscow, where he worked as an engineer in a pencil factory and, eventually, a chief engineer's assistant.. Grossman and his wife were divorced in 1932. Grossman's first literary work to be published was In the Town of Berdichev (V gorode Berdicheve), which appeared in Literaturnaya Gazeta in April 1934. It is the story of a Russian female commissar who, during the Civil War, leaves her baby in the care of a Jewish family so that she can return to the front. The story was praised by Isaak Babel, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Maksim Gorky. Later in 1934, Grossman's first short novel, Gliukauf!, (Gluck auf!) about the life of Soviet miners, appeared. Commenting that Grossman was a "talented man", Gorky made some suggestions to Grossman and had a revised version of the novella published in the almanac Year XVII (1934). Grossman was a member of the Pereval literary group. In 1935, he began an affair with Olga Gruber, the wife of Boris Andreevich Gruber, also a member of Pereval. Olga divorced Gruber and married Grossman in 1936. In 1937, Gruber was arrested and executed as an enemy of the people. Olga was also arrested, on the mistaken belief that she was still Gruber's wife. After about a year and a half in prison, she was finally released. A fictionalized version of these events were later to appear in Grossman's novel Life and Fate. His first novel, Stepan Kolchugin appeared in installments between 1937 and 1940. During the Great Patriotic War, Grossman worked as a correspondent for the Army newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda. In August 1942 the newspaper published his tale The People Immortal (Narod bessmerten), one of the first Soviet novels about the war. Grossman was with the army at Stalingrad, and in 1943 published Stalingrad, a collection of sketches describing the defense of the city, the beginning of the Soviet counteroffensive, and the first stages of the encirclement of the German forces. One of the most memorable of these sketches is In The Main Line of Attack (Napravleniye glavnovo udara). It describes life and death in a division of Siberian troops who had to bear the brunt of the most frenzied period of Nazi attacks on Stalingrad, withstanding 80 straight hours of bombardment, and more. Grossman then traveled with Soviet troops all the way to victory in Berlin. He was the first writer from any country to publish a description of the horrors of Treblinka, The Hell of Triblinka (Treblinskii ad, September 1944). Grossman's mother was among the 20,000 Jews murdered by the Nazis in Berdichev in the early days of the war. During the war, Vasily Grossman and fellow writer Ilya Ehrenburg undertook a project that was to be called The Black Book. Under their direction, over twenty writers worked to document the horrors suffered by Soviet Jewry at the hands of the Nazis. At first, the project was endorsed by the official Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. Later, however, official policy toward the Jews changed. The book was criticized for giving attention to traitors and collaborators among the Ukrainians and Lithuanians, and publication was blocked. It was not until 1980 that a partial version found its was into print. Finally, in 1993, the compete work was published in Lithuania. His most famous and controversial work, Life

and Fate (Zhizn i sudba). As decribed by

Boris Lanin:

Grossman submitted his novel to the journal Znamiya

in 1960, where publication was promised. However,

in February 1961, the KGB "arrested"

the manuscript, and all copies (or so the KGB

thought) were confiscated from Grossman's flat.

|

- Ehrenburg never forgot his Jewish roots, and before his death he arranged for the transfer of his private archives to the tribal cult center at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem.

- And so, it is altogether

fitting that the birthday of this

psychopathic lie-master should have

been chosen as a day on

which to remember the hoax which he

concocted and of which he was the

original inventor.

Re. Survivors of Holocaust:

From: Saul Issroff < 100142.3356@COMPUSERVE.COM >

On 29/4/95. re Sonderkommando and Arnost Lustig-

>From: ajacobs < ajacobs@INTERACCESS.COM

> >Hello,My name is Alan Jacobs. I am new here. I

am not new to Holocaust studies.

>Right now I am trying to find someone who speaks

Czech and knows about the >war. I have tapes of an

interview I did, in 1980 in Mannheim, with Filip

>M=FCller, the former sonderkommando at Birkenau and

author of the book >"Eyewitness Auschwitz, Three

years in the Gas chambers". The interpreter >was

Arnost Lustig. But as he got into many conversations in

thier native >tongue with M=FCller that he didn't

translate, I need some help. Is anyone >interested in

the contents of these tapes? Can anyone recommend an

>enterpreter? Also I have tape of an interview with

Lustig, Milton Buki and >Manya Buki on the same

subject. Milton was also a sonderkommando at

>Birkenau. Manya worked in the Sauna disinfecting

clothing from the camp and >from the transports with

Zyclon B.

>Also is anyone here familiar with an Oswiecim State Museum publication: "Amidst a Nightmare of Crime, Notes of Prisoners of Sonderkommando Found at >Auschwitz" (1973)? These are notes written in Yiddish and stuffed in >various containers and buried beneath the ashes at Krematoria II & III, >Birkenau. Is anyone interested, or is anyone working on a study of the >sonderkommnando?

"I speak Czech. I am one of the Birkenau Boys, do

you know about us? If not

please obtain a book;

'After Those Fifty Years', (Memoirs of the Birkenau Boys)

edited by John Freund and obtainable from him. His address is:-

John Freund

184 Highbourne Road

Toronto

Ontario, Canada M5P 2J7, Tel.No. 416 481 1933

I was in Birkenau 15th Dec. 43 to 24th Dec. 44. In

July 44 about 90 boys were

transferred from the so called Czech Familienlager

(Abschnitt BIIb) to the Maennerlager. There we were

accomodated in the Straffenblock next to the

Sonderkommando. I had been a Laeufer (runner) for the

hospital block in BIIb

and ran errands for Mengele, in the Maennerlager I became

Laeufer for the Kleiderkammer (clothing department). The

Maennerlager (Abschnitt BIId) was a

service camp for the whole of Birkenau. The men of the

Sonderkommando befriended us, fed us and helped in all

sorts of ways. It was a special thing

that they had contact with Jewish children who were

alive. I spent the first

three days in the Maennerlager with them and a foreman of

one of the Sonderkommando gangs called Geille got me a

pair of skiing boots which saw me

through the evacuation right up to the time I had a sauna

just before typhus in Mauthausen in May 1945.

Geille was the foreman of the gang of crematorium III which was blown up by the Sonderkommando in October 1944. Their revolt lasted about half an hour and all of them were shot.

As I had access to roads round the Birkenau camp

Geille asked me to tell about

10,000 Hungarian Jews that they were waiting to be

gassed, they were camped out on the road between the

Maennerlager and the BIIc Abschnitt, I was to ask

them to start a riot when they heard the explosion. Some

men took me to a Rabbi who heard me out and asked why my

Yiddisch was like Taich. I explained

that I was from Czechoslovakia and that up to Auschwitz I

had heard my parents

speak to Polish Jews and always understood Yiddisch but

that I only started speaking the language in the camp.

The Rabbi chose not to believe me because

I was smartly dressed as a Laeufer and had special

permission to grow my hair.

He turned to the bystanders and accused me of being a

provocateur. The revolt had no support at all, and in due

course the people waiting were the last group of

Hungarian Jews to be gassed. When they were finnished the

Germans started dismantling the gas chambers and

crematoria, leaving only crematorium II to service the

corpses of the dying, there was no shortage of bodies.

I write extensively, not necessarily about the

Holocaust, my subject is Jewish

genealogy. I will be in the US at the Washington DC

summer seminar on Jewish

Genealogy taking place 24th to 29th June. We could meet.

I am willing to help you all I can. There are several

others of the boys some in the US who could also tell you

more stories about the Sonderkommando in Birkenau. I

speak Czech, a bit of Polish, Hebrew & Yiddish and

have done a number of translations.

.................................................................................

Jorge Semprun, a Spaniard and a French man of letters also deals with Buchenwald and Weimar in his book published last year, Writing or Life, which probably will be soon translated into English. Semprun who was for a while Minister of Culture in Felipe Gonzales cabinet, was during the war a young student of philosophy in Paris. He fought in the resistance, was captured in 1944 and sent to Buchenwald. He was twenty at that time.

The book is an autobiographical narrative, focused on the day of liberation and its aftermath with flashbacks to being a Buchenwald prisoner. It is a remarkable account.

Semprun, a gentile, has a profound respect for the Jews, whose conditions were much worse. He tells about an Auschwitz Sonderkomando Jew who somehow remained alive and was sent to Buchenwald. This person met with the resistance committee and recounted his Auschwitz experience. After some minutes of silence, the head of the group, a German prisoner by the name of Kaminski asked everybody to remember Germany. Germans did the atrocities.

After liberation Semprun, like many others, contemplated suicide. He feels himself akin to Primo Levi and attempts a bold interpretation for the reason for his suicide.

I recommend the book to everybody.

Aharon Meytahl

From: Froma I. Zeitlin < FIZ@PUCC >

Semprun is the author of a 'classic' book on the Holocaust experience, called the Long Voyage (published many years ago in French and available in English, still in print). He uses flashbacks there as the entire work takes place on the trains.

............................................................................................................

There was a program on the Arts & Entertainment Network Sunday night that I had not seen before about Hitler that mentioned his Catholic upbringing in Austria and the fact he had been a member of the church choir. It showed an interior shot of the church that he sang and over one of the carved saints was an escutcheon shield in which was centered a swastika sitting flat (cross style rather than cocked 45 degrees the way the Nazis later adopted) with pointed arms in a semi-sunwheel style. The earliest Nazi flags had the swastika sitting flat on one arm and was later cocked at the angle everyone is familiar seeing. Anyway, that is the best connection I have seen presented yet as to how Hitler came up with the swastika symbol.

As for the other runic symbols used by the Nazis there were many. The SS in particular used them in an adapted form. Many of the foreign Waffen SS units had collar insignia that was derived from Nordic runic symbols and those symbols also appeared on the SS officer's rings. The tyre rune (upward pointing arrow) was used in the Nazi party to distinguish graduates of the Nazi leadership school. The "wolfsangle" was used by the Dutch SS volunteers. The sunwheel or mobile swastika was used by the 5th SS Panzer Division etc. etc.

The SS used those symbols to try to create a mystic aura of the Viking days with all that blond hair, blue eyed terror of the seas stuff. The SS, being the essence of Germanic manhood identified closely with all that Teutonic Knight ideal.

Cheers, Bill Huber / whuber@sadis01.kelly.af.mil

........................................................................................................................

- Allied Indifference:

From: Paul Lawrence Rose < PLR2@PSUVM.PSU.EDU >

It is difficult to take seriously the Jerusalem Report feature of 12 Jan. excusing the bombing of Auschwitz. One subsequent published comment by a Polish gentile witness in the issue of 23 March may interest readers: "US Air Force apologists mentioned in Why Didn't the Allies Bomb Auschwitz speak of an "umbrella" of hundreds of Luftwaffe fighter planes and "79 heavy guns" defending Auschwitz from air attack. All this is imaginary. In 1944 I was a prisoner in Ausch. working as "captain" of one of the camp's three fire trucks. We were responsible for checking the fire-fighting equipment in the heavily industiral 40 sq. km. area...During the summer of 1944 there were several US air-raids on this area, and I watched them through binoculars. Only once did I spot two German fighter planes. They "defended" the area by flying scared and at tree-top level, while high above them 90 US Superfortresses flew nonchalantly by. In 1944 there were 17 (not 79!) anti-aircraft guns in the area. They were manned by Italian gunners and were chronically short of ammunition. Sigmund Sobolewski. Vice-President, Auschwitz Awareness Society, Alberta, Canada". Mr Sobolewski is well-known and appreciated for his countering of the various denial myths that have sprung up about Auschwitz. PLRose PLR2@psuvm.Psu.Edu.

- ..................................................................................................

Exterminations: Gypsies

Baranowski, who investigated the transports to Chelmno, says that 150,000 to 160,000 Jews from Wartheland and West Europe and over 4,000 Gypsies were killed in Chelmno. It confirms the earlier evaluations of Raul Hilberg, Adalbert Rueckerl and other scholars.

Take nothing on its looks, take everything on evidence. There is no better rule. (Dickens, Great Expectations)

A Lesson to be Learned?

I taught a Holocaust memory class this year for the first time. It has been a very rewarding process. In the beginning of the class I ask the students why they take this class and to draw associations, verbal or visual, to the Holocaust. The most common answer to 'why' is 'so it will never happen again.' It's so automatic, it makes me sick. It's so pat, and some of these students have grandparents they have never even sat down with to listen to their story!

There are many important things that have been learned

from studying the Holocaust, that have contributed to the

world. there is no ONE lesson that comes from studying

the Holocaust. If a survivor shares his or her story, and

they see that this makes a difference to those listening,

that is one answer to the question. Creating new memories

of the sharing of memories, that is community. But, to

prevent another Holocaust? or undo the effects of this

one? or make this a better world? or never again???

........................can't promise that. Besides, in

Judaism, the imperative is 'never forget,' not 'never

again.' lucia@bgumail.bgu.ac.il

I'm becoming increasingly suspicious that teaching our

students (for example) about the Holocaust (for example)

will make much of a difference in how they subsequently

behave as human beings. I at least have seen no evidence

to suggest that, *because* they have studied the

Holocaust, most of my students have become more

compassionate human beings who actively fight to help

victims. In fact, most seem to remain in a state of

self-deception about the extent to which, notwithstanding

their sympathies for the victims and their outrage at

what happened, they themselves participate in quotidian

and often subtle acts of promoting evil (who *doesn't*

participate in such acts!?). On

the other hand, I *have* discovered that the few truly

compassionate students who come to the class already

committed to fighting for peace and justice seem to take

away from the class a renewed and more heightened sense

of commitment.

Ordinary People and Extraordinary Evil,Katz's

book: "Mourning and massive commemorations confer

little or no immunity against future social horrors.

Teaching about horrors relies heavily on the assumption

that people will experience such revulsion that they

will, under no circumstances, engage in such horrors,

that revulsion will serve as a vaccine against committing

horrors. Yet one thing we learn from the life of Hoess is

that a person can have a real sense of revulsion about

murderous activities, yet engage in them with alacrity

and fervor" Richard Prystowsky (RJPrys@aol.com)

many widespread practices in human affairs were

"sins" long before they were recognized as

"crimes" and penalties were set to confront

them. Such are duelling, widow-burning, feuding,

infanticide, cannibalism, infibulation, chattel slavery,

genocide, drawing & quartering, human sacrifice... It

takes long centuries before a society's conscience has

been elevated to the point where people recognize that

something is basically WRONG, and not like an earthquake

or a flood but rather by human action (a CRIME). Then

laws must be articulated to penalize the wrongdoing for

the sake of social justice and also to cause second

thoughts in those tempted to so the same. But there is a

time lag between the point where a CRIME is identified

and penalties enacted, and the point when the laws can be

enforced. That is where we are with "genocide,"

long a sin but only since 1951 defined as a

"crime." Only the first steps have been taken

toward enforcing penalties for the crime. Franklin

Littell <FHL%TEMPLEVM@UICVM.CC.UIC.EDU>

When I was an undergraduate, I approached my advisor

about doing an honors thesis on women in Nazi Germany. He

said there was no point; there was nothing out there. He

was wrong; Jill Stephenson's material, for example, was

already appearing. He just wasn't keeping up with the

literature. I took his word for it & dropped my idea

for an honors thesis. This probably represented no great

loss to the historical literature, but it WAS a lesson

(once I realized what had happened) about how vulnerable

students are when we, as professors, fail to keep up with

recent developments in the field. Certainly now, after

nearly 20 years of German-language writing on women in

Nazi Germany, and after nearly 15 years of

English-language writing, there's not much excuse for

leaving students wondering whether anything whatsoever is

known about the subject.

--Elizabeth Heineman

Alan Jacobs < ajacobs@INTERACCESS.COM >

I don't think that teaching history will stop anyone

from comitting murder. Perhaps what we need is to teach

people why the SS did it? Perhaps engage students in this

question, let them speculate. Nothing like engaging them

in the speculation because then they have to think.

Scaring or horrifying them only gets them to turn away

from it, denial being what it is. Most of us here have

plenty of horror stories and images in our heads. I don't

think it enough, for whatever my intense preoccupation

with the subject. So I am proposing here the question...

Why did they do it? Why, socially, psychologically,

spiritually or in any other way you choose to define it.

Alan Jacobs

Psychotherapist

One survivor whom I interviewed told me that, after the

war, he decided to become a physician. Why? Because,

having suffered such trauma himself, he wanted to heal

the world? No. Not even close. Among other things, he

wanted to figure out a way to poison the German water

supply in retaliation for what had happend to him and his

people. My hunch is that Ted Kopple won't invite this

survivor to tell his story on _Nightline_. Nor will he be

used in an ad requesting funds for a humanitarian cause.

There's no underlying sense of redemption in his

testimony, no sense of sustained or renewed hope, and

certainly not much to recommend from the standpoint of

spirituality. In fact, there's much raw pain and deeply

felt hate.Richard Prystowsky (RJPrys@aol.com)

The Annual Scholars' Conference on the Holocaust and the

Churches was founded in 1970 by Franklin H. Littell and

Hubert G. Locke as an interfaith, interdisciplinary and

international organization. Devoted to remembering and

learning from the Holocaust, and encouraging the

participation of educators from both campuses and local

communities, its mission is to promote scholarlyresearch

by both Jews and Christians that examines issues raised

by the "Final Solution."

Polish Foreign Minister Wladyslaw Bartoszewski met

Wednesday with Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Foreign

Minister Shimon Peres to discuss political issues,

MA'ARIV reported. Bartoszewski promised that Poland will

continue to support Israel fight against anti-semitism

and terrorism. The Polish Foreign Minister is an honorary

citizen of Israel and the recipient of Yad Vashem's

"Righteous Among the Nations" award.

Bartoszewski will participate today in a ceremony at the

Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial.

The Poet

Holocaust is really a prose poem in book form. It is called "Holocaust" and is by Charles Reznikoff. The book was published by The Black Sparrow Press. Reznikoff is one of this century's great Jewish writers and poets.

Holocaust is well worth reading (it is based on a reading of the Nuremburg transcripts by Reznikoff) as is all the work of this writer.

Holocaust_ was a breakthrough volume not only because Reznikoff made use of the War Crimes Trial records but also because he showed that an entire book of poetry could be devoted to the Holocaust by a writer who was neither a European nor a KZ survivor. Sections of _Holocaust_ will appear in _On Broken Branches: World Poets on the Holocaust_ (no projected publication date at this time).

Reznikoff's complete poems are available in two volumes from Black Sparrow Press, ed. Seamus Cooney: Vol. I, 1918-1936; Vol. II, 1937-1975.

--C. Fishman